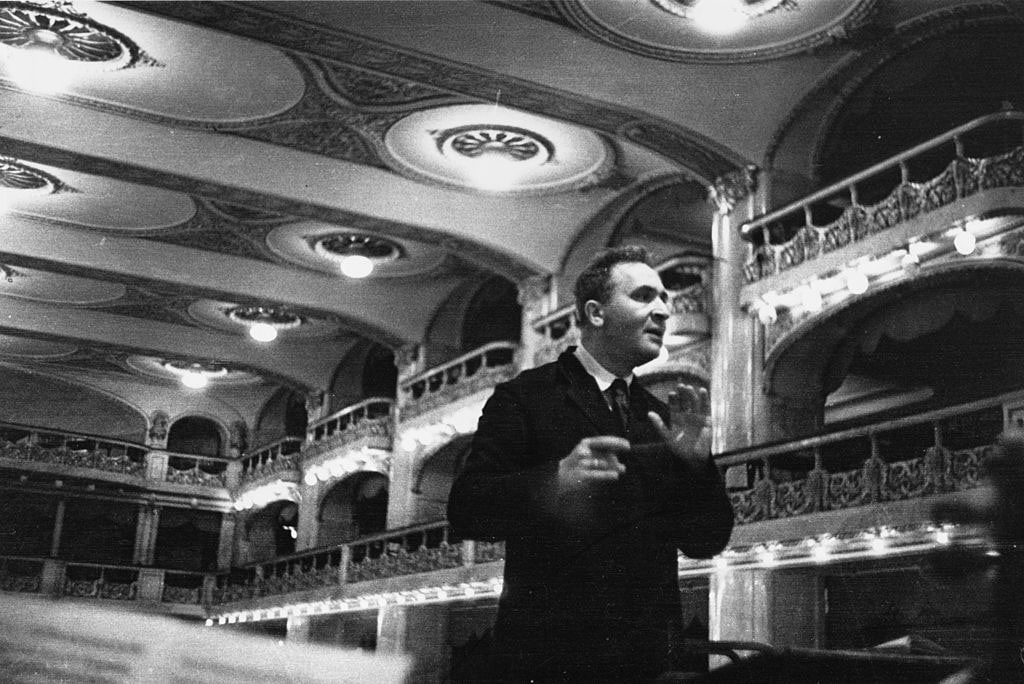

It was not his ability to inspire people with interpretive comprehension that made Bruno Walter

a great conductor, but his faith in music — especially of Mozart and of Mahler! — he loved to conduct,

abandoning the religious faith from which he, just like Mahler — professionally pragmatic — had converted.

Olin Downes, a major New York Times affiliated music critic,

identified in this quite unobservant Jew a quality that is semitic:

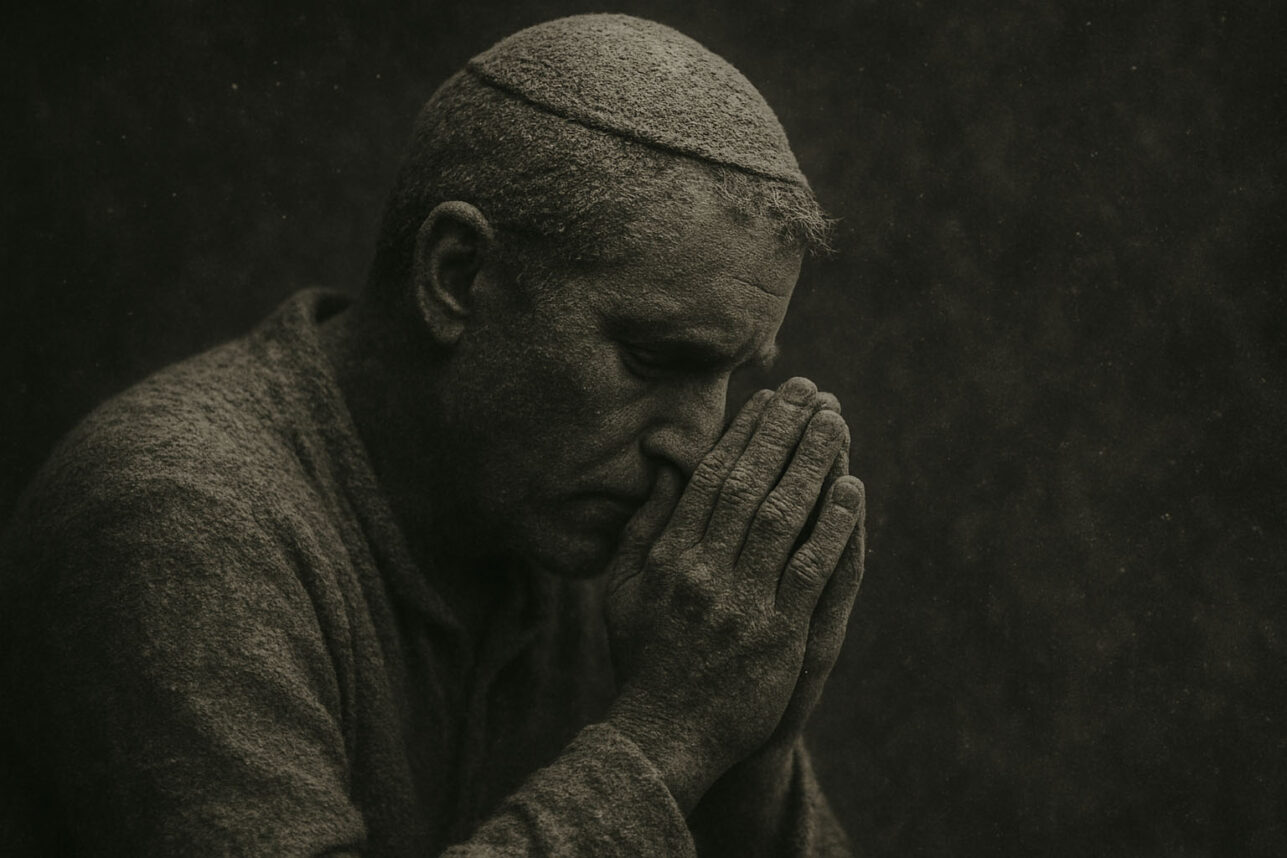

deep faith, a quality required from all rabbis who instruct

their followers by faithful concentration on their sacred literature, making efforts most concerted

to broadcast what they might interpretively comprehend to Jewish homes, which act both as their pulpit and their altar.

Truth can be repulsive,” Bruno Walter, a conductor whose life had taught him that fact all too well, once said. “But Mozart has the power to speak truth with beauty.”

If there was one composer that Walter, who was able to make beauty from truth like few others until his death in Beverly Hills in 1962, was most associated with during his career, it was that Viennese master; the story of Walter’s life, the conductor said, could be told as “the history of the development of a love for Mozart.”

Writers often dignified Walter with spiritual metaphors — the author Stefan Zweig compared the beam on his face while conducting to “the countenance of the angels when they look upon God” — and it is revealing of his artistry that they were exactly what Walter aspired to achieve. For him, the Germanic music from Bach to Strauss was pure, uplifting, redemptive. It offered an “unchanging message of comfort,” he wrote in his memoir “Theme and Variations”; its “wordless gospel proclaims in a universal language what the thirsting soul of man is seeking beyond this life.”

Gershon Hepner is a poet who has written over 25,000 poems on subjects ranging from music to literature, politics to Torah. He grew up in England and moved to Los Angeles in 1976. Using his varied interests and experiences, he has authored dozens of papers in medical and academic journals, and authored “Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel.” He can be reached at gershonhepner@gmail.com.