Jewish Contributions to Humanity #11:

Original research by Walter L. Field.

Sponsored by Irwin S. Field.

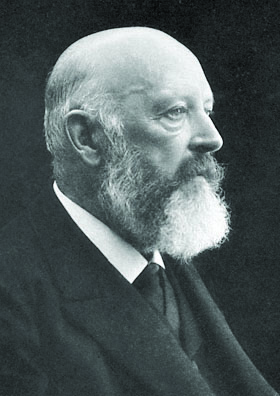

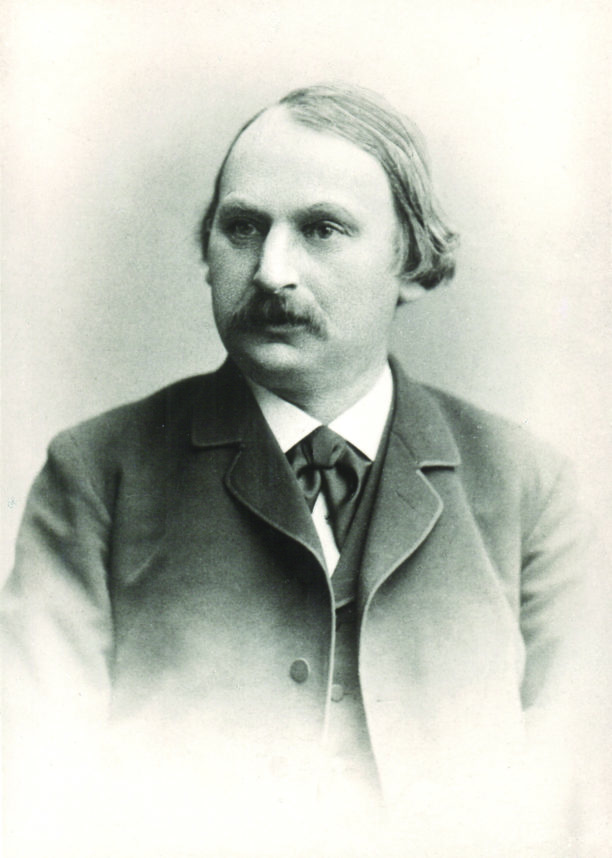

Adolf von Baeyer (1835-1917). b. Berlin, Germany. Nobel Prize in Chemistry—1905. The jeans chemist.

Jeans, you may be surprised to learn, are not naturally blue. No, that’s in fact thanks to Adolph von Baeyer, who synthesized in 1880 indigo, a blue dye. This little known scientist made some other invaluable contributions, including his discovery of barbituric acid (which led to the manufacture of types of sedatives and anesthetics), and fluorescein, which forensic investigators use to find blood and other stains.

Jeans, you may be surprised to learn, are not naturally blue. No, that’s in fact thanks to Adolph von Baeyer, who synthesized in 1880 indigo, a blue dye. This little known scientist made some other invaluable contributions, including his discovery of barbituric acid (which led to the manufacture of types of sedatives and anesthetics), and fluorescein, which forensic investigators use to find blood and other stains.

Adolph Frank (1834-1916). b. Klotze, Germany. Putting food on the table.

Every year globally, more than 30 million tons of potash are produced. The main ingredient of which is potassium, potash is one of the most crucial artificial nutrients in agriculture. Who do we have to thank for discovering that potash could be a fertilizer that could help feed humanity? Adolph Frank, another unheralded but hugely impactful German Jewish scientist. Additionally, Frank also invented a way to extract bromine from salt mines. Bromine has served humanity well—as a flame retardant, a pesticide, and a sedative.

Every year globally, more than 30 million tons of potash are produced. The main ingredient of which is potassium, potash is one of the most crucial artificial nutrients in agriculture. Who do we have to thank for discovering that potash could be a fertilizer that could help feed humanity? Adolph Frank, another unheralded but hugely impactful German Jewish scientist. Additionally, Frank also invented a way to extract bromine from salt mines. Bromine has served humanity well—as a flame retardant, a pesticide, and a sedative.

Richard Willstatter (1872-1942). b. Karlsruhe, Germany. Nobel Prize in Chemistry—1915. How light turns into energy.

A protégé of Adolph von Baeyer at the University of Munich, Willstatter was the first ever scientist to determine the chemical formula of chlorophyll, a vital chemical in photosynthesis (the process by which sunlight is converted into energy). This was the main contribution for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize. In 1917, when his friend Fritz Haber (see below) asked him to develop poison gas to advance Germany’s interest in World War I, Willstatter declined—and instead offered to help develop a defensive filter to poison gas, which led to the first gas masks.

A protégé of Adolph von Baeyer at the University of Munich, Willstatter was the first ever scientist to determine the chemical formula of chlorophyll, a vital chemical in photosynthesis (the process by which sunlight is converted into energy). This was the main contribution for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize. In 1917, when his friend Fritz Haber (see below) asked him to develop poison gas to advance Germany’s interest in World War I, Willstatter declined—and instead offered to help develop a defensive filter to poison gas, which led to the first gas masks.

Fritz Haber (1868-1934). b. Wroclaw, Poland. Nobel Prize in Chemistry—1918. The master of chemicals, for good and bad.

Haber sits in the center of what was truly a golden age of Jewish chemists. He and Adolph Frank are responsible for feeding much of humanity—the Haber Process, which produced ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen, is responsible for the creation of agricultural fertilizers (500 million tons are produced annually) that now help feed a substantial portion of humanity. Haber’s creation of ammonia has even been credited with “detonating” the population explosion from 1.6 billion people in 1900 to more than 7 billion today. Why? Well, to feed the increasing world population would have been impossible if the relatively inefficient methods of agriculture in that era didn’t improve. Ammonia-based fertilizers allow for farms to grow far more food than they could have grown in the past. Haber, though, must also be remembered as the head of the German military’s chemistry wing during World War I. He supervised the first use of chemical weapons (chlorine gas) in military history and also of chemical defense (gas masks) in modern warfare. His legacy is a mixed one—greatness for his role in agricultural chemistry; controversy for his part in the chemistry of warfare.

Haber sits in the center of what was truly a golden age of Jewish chemists. He and Adolph Frank are responsible for feeding much of humanity—the Haber Process, which produced ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen, is responsible for the creation of agricultural fertilizers (500 million tons are produced annually) that now help feed a substantial portion of humanity. Haber’s creation of ammonia has even been credited with “detonating” the population explosion from 1.6 billion people in 1900 to more than 7 billion today. Why? Well, to feed the increasing world population would have been impossible if the relatively inefficient methods of agriculture in that era didn’t improve. Ammonia-based fertilizers allow for farms to grow far more food than they could have grown in the past. Haber, though, must also be remembered as the head of the German military’s chemistry wing during World War I. He supervised the first use of chemical weapons (chlorine gas) in military history and also of chemical defense (gas masks) in modern warfare. His legacy is a mixed one—greatness for his role in agricultural chemistry; controversy for his part in the chemistry of warfare.