From left: Carol Bishop captures “Bishop10 Aharonovitz St., Brazilai-Haussmann 1937” and “35 Petah Tikvah Rd. Rekanati House, Shlomo Leaskovsky-Yaakov Orenstein, 1935.” Photos courtesy of Carol Bishop

From left: Carol Bishop captures “Bishop10 Aharonovitz St., Brazilai-Haussmann 1937” and “35 Petah Tikvah Rd. Rekanati House, Shlomo Leaskovsky-Yaakov Orenstein, 1935.” Photos courtesy of Carol Bishop The famed modernist apartment buildings that line Tel Aviv’s streets have earned the Israeli port city the nickname the “White City.” Influenced by the International Style of modern architecture in the 1930s, the buildings reflect the prevalent vision that shaped the city’s creation and left an architectural legacy recognized with a World Heritage Site designation.

Two Los Angeles-based photographers, Susan Horowitz and Carol Bishop, examine that legacy in an exhibit called “Tel Aviv — The White City + Beyond,” now on display through May 28 at the Academy for Jewish Religion, California in Koreatown.

“The style came from the idea of ‘new’: a clean slate. And what was more new than these ideas about buildings?” Bishop said.

“When they needed to accommodate so many people streaming into Israel, they felt that that would be the newest style and one without reference to older design and other cultures,” Horowitz added.

When Jewish settlers came to Palestine in the early 1900s, they worked with British colonial administrators to build a new city on the sand dunes north of the ancient city of Jaffa. The architects of that era drew inspiration from the International Style of architecture that took hold in Europe immediately after World War I. The style emerged from the Bauhaus School of Arts, Design and Architecture, which Walter Gropius founded in Weimar Germany in 1919. (The Nazis closed the school in 1933.)

The rise of Nazism led to a mass migration of European Jews to Palestine in the 1930s. Tel Aviv’s rapid growth meant an immediate need for housing and no shortage of work for architects. Among them was Arieh Sharon, a Bauhaus-educated architect who designed workers’ housing, private homes, cinemas, hospitals and government buildings.

Approximately 4,000 Bauhaus-style buildings were built in Tel Aviv in the 1930s and ’40s — the largest collection in the world. The buildings were collectively recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage site in 2003, and guided tours of the White City are still popular with tourists.

Bauhaus-style architecture emphasizes functionality and eschews decorative elements. The Tel Aviv buildings resemble white blocks with clean, flowing lines and smooth surfaces, the facades interrupted only by inset windows and balconies. The architects adapted their style to the sunny Mediterranean climate, maximizing ventilation by placing the buildings on pilotis, or ground-level support columns, to create shady outdoor areas.

Horowitz and Bishop, longtime friends and colleagues, combined their images in one show to reveal two different perspectives on Tel Aviv.

Bishop’s part of the exhibit, called “Colors of the White City,” is made up of color photos, with green palm trees and bright, blue skies framing the gleaming buildings. She also includes a sepia-toned series of photos of Jaffa’s old buildings, and a conceptual series focused on the use of limestone bricks.

Horowitz’s photos, in her part called “Perspective — The White City,” are black and white and often include nearby buildings to juxtapose the white Bauhaus-style apartments with their more contemporary (and far less stylish) neighbors.

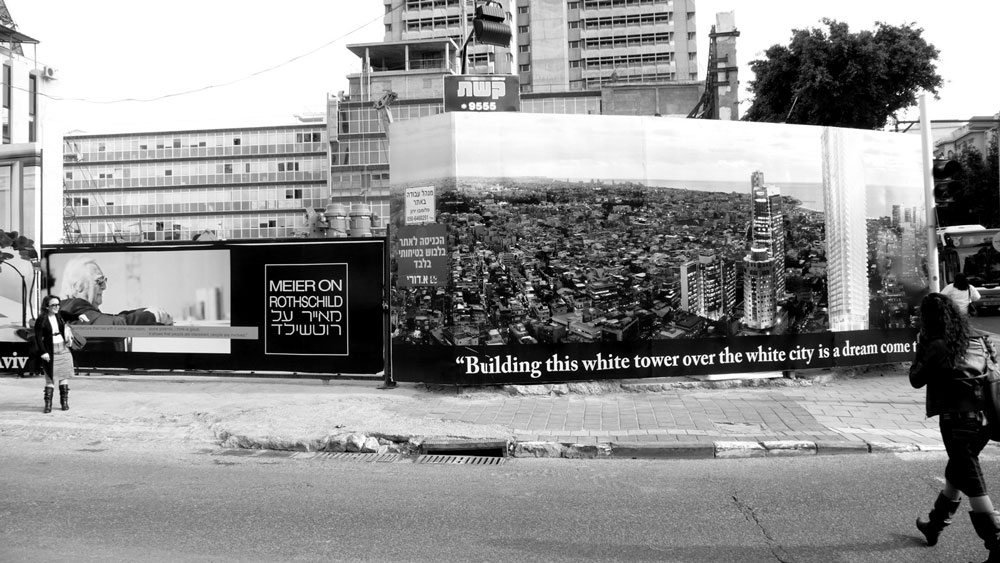

One photo by Horowitz shows a billboard promoting “Meier on Rothschild,” a mixed-use complex designed by American architect Richard Meier (designer of The Getty Center in Los Angeles) that opened in 2015 and includes a 39-story building — Meier’s take on Bauhaus architecture. The billboard displays a quote from Meier: “Building this white tower over the white city is a dream come true.”

When she first arrived in Tel Aviv, Bishop said, she was struck by its similarities to Los Angeles, such as the climate, the culture, the age of the buildings and the integration of indoor and outdoor spaces. She also noticed another parallel: Just as L.A. is attempting to preserve modernist buildings that have fallen into disrepair, so, too, is Tel Aviv rehabilitating some of its decaying Bauhaus-style buildings.

Horowitz, during her research, discovered another connection between Tel Aviv and L.A. through the work of architect Ben-Ami Shulman. He was born in Jaffa in 1907, studied at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels and became one of the noted modernist architects in Tel Aviv in the 1930s. After moving to Los Angeles in 1960, Shulman built residential and commercial buildings in a nondescript style often referred to as “vernacular architecture.”

Horowitz photographed all 17 documented Shulman buildings in L.A., as well as eight Shulman buildings designated as landmarks in Tel Aviv, and organized them into a mini-exhibition she calls “Some Shulman Architecture,” which is included in the “White City” show. (The title is a reference to artist Ed Ruscha’s iconic photographic series “Some Los Angeles Apartments,” that draws attention to easily overlooked or banal elements of the built environment.) Horowitz’s Shulman project was previously displayed at the American Institute of Architects’ Los Angeles office in 2015.

Not everyone accepts the historic narrative of the White City, however. In his book “White City, Black City: Architecture and War in Tel Aviv and Jaffa,” dissident Israeli historian and architect Sharon Rotbard notes that only four Bauhaus students ever emigrated to Palestine, and they were more influenced by Swiss-French architect Le Corbusier. Tel Aviv began as a suburb of Jaffa, but its population boom in the 1920s soon came to overshadow the Arab economic and cultural hub. Since Jaffa’s annexation to Tel Aviv after the 1948 war, most of Jaffa’s residents were pushed out and its neighborhoods were bulldozed.

“Tel Aviv eagerly appropriated the Bauhaus brand name in order to develop the local myth about the rebirth of Bauhaus in Palestine,” says Rotbard, who contends that the story of a gleaming white city built on sand dunes is a “fable” created to serve “obvious political and economic agendas.” While the Bauhaus school emphasized utopian social ideas, Rotbard argues that Tel Aviv’s modernist architecture was used for colonial purposes: to whitewash the dispossession and expulsion of the Palestinians.

But to label the White City as a “colonial” architectural project is inaccurate, Bishop argued.

“I think the word ‘colonial’ is a little tricky,” she said. “I would say utopian. A dream that, finally, in our own power, we can visually — and, of course, culturally — start anew.”

“Tel Aviv — The White City + Beyond” by Carol Bishop and Susan Horowitz is on display through May 28 at the offices of the Academy for Jewish Religion, California, 3250 Wilshire Blvd., No. 550, Los Angeles.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.