Manifest destiny, woke-labeled catastrophe,

resembles regarding as racist the wrong quest

by Normans for England in their famous “Conquest,”

the quest for the west, trashed as base bad-ass trophy.

The manifest destiny of Jews may be

compared to that of Normans in 1066,

the loss it caused to Arabs a calamity

that, unlike Anglo-Saxons, they refuse to fix,

except by their denial to accept defeat

in contrast to all the Hastings Battle losers,

unwilling their loss as reality to treat,

of the addictive substance of illusion the abusers.

If indigenous Americans adopt the same approach

they might transform a destiny Americans had all believed

was manifest into a cockamamie Kafkaesqe cockroach

instead of the imperial identity by which they’d been deceived.

We Jews throughout the world have for millennia regarded

our destiny as the major manifestation of not just

our Fate but of a Covenant with God that will not ever be discarded:

the Covenant of Destiny made with a God in whom we trust.

Menachem Begin, realizing this when meeting Jimmy Carter,

whose attitude towards him was manifestly hateful,

did not let Jimmy make the Jewish State become Maranathan martyr,

inspired more by the Covenant of Destiny than the fatal one that’s fateful.

President Jimmy Carter was a member of the Maranathan Church.

In “The First Tisha B’Av Since October 7: Jewish history saw the transition from the Covenant of Fate to the Covenant of Destiny, and back again,” Sapir, Summer 2024, August 8, 2024, Benny Lau writes:

After the Yom Kippur War, when Israel’s near-defeat had a sobering effect on the messianic fervor. In response, the country split into two distinct directions. One side pulled Israel east, toward traditionalist and religious nationalism. The other pulled Israel west, toward secular liberalism. These opposing winds kept blowing, eventually forming the storm of judicial reform, until October 6, 50 years to the day after the start of the Yom Kippur War — when the split began.

The eastern and western pulls weren’t merely figurative but literal. Those imbued with the eastern spirit excitedly gravitated toward the Temple Mount, the Cave of the Patriarchs, Joseph’s Tomb — places associated with the roots of the Jewish national story in the Bible, in the east. The Western intellectuals chose to turn a cold and alienated shoulder to exactly these places. To them, these sacred sites were symbols of the Jewish occupation and control of the Palestinian people.

But there was something these spirits had in common: an undeniable feeling that the exile had ended. In the language of Jewish thought, from the secularists of Labor Zionism to the religious writings of Joseph B. Soloveitchik, this paradigmatic change was defined as the transition from a “Covenant of Fate” to a “Covenant of Destiny.”

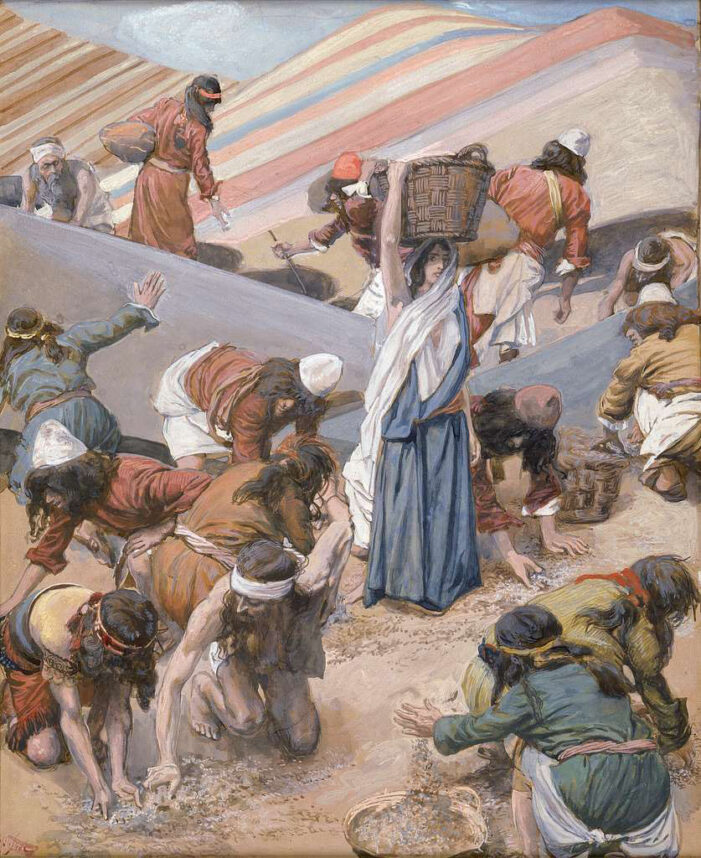

The Covenant of Fate expressed the existence of the Jewish people as a persecuted minority in the lands of the Diaspora, beholden to the choices and external powers around them. It was a mode of survival built on a common memory of powerlessness.

The Covenant of Destiny was configured around the opposite: power and agency, the will to express the Jewish experience through a national mission, unencumbered by external powers, seeking to realize its special role in history as a member in the family of nations, to be an am segula, a term often translated as a “treasured nation,” but more accurately, a “dignified one.”

In a podcast on/14/24, “How Torah Changed the World,” Rabbi Meir Soloveichik said:

Soon after his election in 1977, Begin came to America in the days before Tisha b’Av. Prior to visiting the White House, he took a trip to Brooklyn to meet with the Lubavitcher Rebbe. Asked by curious journalists why a political leader was stopping to speak with a hasidic leader, he said:

I have come tonight to our great master and teacher, the Rabbi, to ask from him his blessings before I go to Washington to meet President Carter for the important talks we are going to hold on the future of the Middle East. The people in Israel pray for the success of these very important meetings.

And then Begin added,

I do not call them ‘fateful’ meetings, because the people of Israel, the Jewish People, are an eternal people, and their lot and future are not dependent on a political meeting with the leader of the free world. [emphasis added]

Soon after his election in 1977, Begin came to America in the days before Tisha b’Av. Prior to visiting the White House, he took a trip to Brooklyn to meet with the Lubavitcher Rebbe. Asked by curious journalists why a political leader was stopping to speak with a hasidic leader, he said: I have come tonight to our great master and teacher, the Rabbi, to ask from him his blessings before I go to Washington to meet President Carter for the important talks we are going to hold on the future of the Middle East. The people in Israel pray for the success of these very important meetings. And then Begin added, I do not call them ‘fateful’ meetings, because the people of Israel, the Jewish People, are an eternal people, and their lot and future are not dependent on a political meeting with the leader of the free world. [emphasis added]

Gershon Hepner is a poet who has written over 25,000 poems on subjects ranging from music to literature, politics to Torah. He grew up in England and moved to Los Angeles in 1976. Using his varied interests and experiences, he has authored dozens of papers in medical and academic journals, and authored “Legal Friction: Law, Narrative, and Identity Politics in Biblical Israel.” He can be reached at gershonhepner@gmail.com.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.