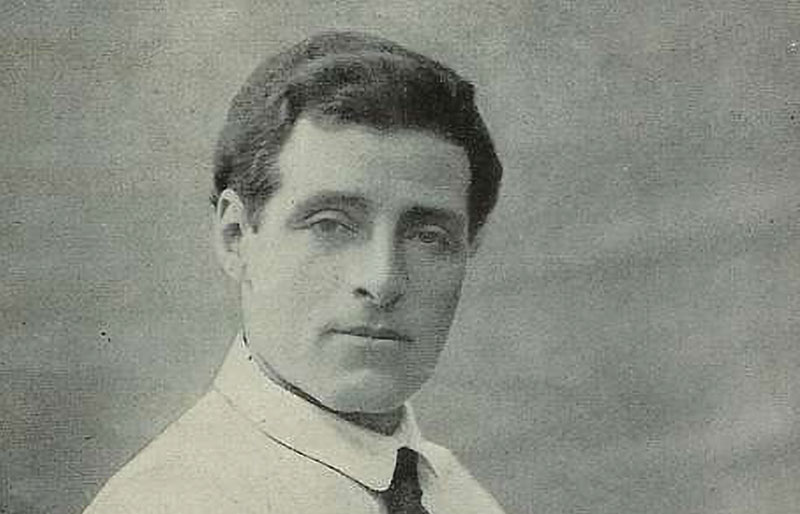

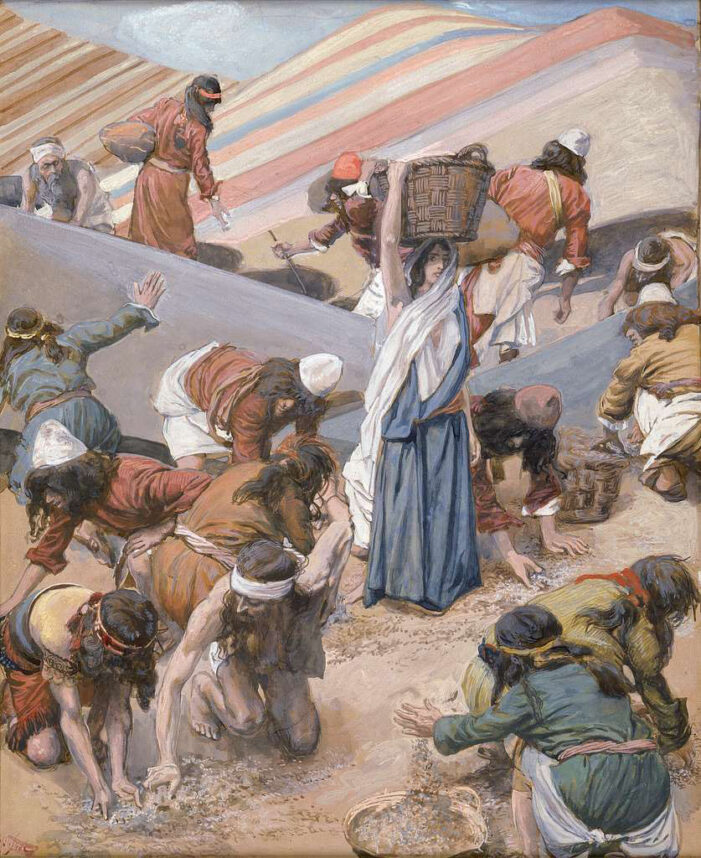

At the meeting of the Provisional Committee for the Jews of Israel, on February 25, 1920, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, a Revisionist Zionist leader, addressed the labor organizations “with a firm request.” In the protocol, his words were summed up in this way: “To immediately call on Joseph Trumpeldor and his friends to evacuate Tel Hai and return to the British occupation territory.” Trumpeldor was a friend of Jabotinsky, a leading Zionist leader, and a Russian war hero. Tel Hai was where he lived. A remote, tiny settlement, in northern Israel, not far from today’s Lebanese border.

If the Arabs would attack Tel Hai, Jabotinsky said, there will be no way for us to protect them. They will have no way to protect the settlement, not for long. It was isolated, small, remote. Attempting to defend it will have one possible result: The blood of the Zionist settlers will be shed in vain. Jabotinsky’s call of reason was simple. Get them back, evacuate, abandon Tel Hai. Staying put is not a sign of resilience, it is just irrational miscalculation.

The leaders of the Zionist labor-left rejected the request of the right-wing leader. David Ben-Gurion thought that “if we flee because of the threat of bandits, we will have to leave not only the Upper Galilee, but the entire Land of Israel.” On March 1, a few days after Jabotinsky’s emotional appeal was rejected, eight of the defenders of Tel Hai fell, Trumpeldor included. His controversial last words are known to all Israelis: “It’s nothing, it is good to die for our country.” Some historians still argue that he never said those words, but most assume that he did.

Journalist Ofer Aderet, in a book he penned about seven such Zionist Legends, articulates the question of insisting on staying in Tel Hai amid the grave warning in these words: “Was the battle an example of courage and bravery, or was it the result of an unimportant or meaningful insistence on clinging to the land?” The same question is repeated in the annals of all nations, and in the annals of the people of Israel. In essence, there is no difference between this question and the question of sticking to the Philadelphi corridor – the disputed strip of land separating the Gaza Strip from Egypt.

On the one hand, there is a strategic consideration, which may be real (without keeping the Philadelphi line under Israel’s full control, Gaza will return to being a hive of terror) or may be miscalculated (the Israeli interest can be guarded, and the border can be secured, without having boots on the Philadelphi ground). On the other hand, there is the fear for human lives, the concern for blood of hostages and soldiers shed in vain.

In some way, Philadelphi is more complicated than Tel Hai, because of the need to take into account both the blood of hostages and that of soldiers. In the short term, the lives of the hostages are on the line, as Israel’s insistence on keeping the Philadelphi corridor complicates any imaginable hostage deal with Hamas. But the long-term concern for human lives is also high. Protecting the Philadelphi corridor will not be without tactical complications. Soldiers stationed there will have to guard themselves against snipers, roadside bombs and all other means of attack against a stationary force. In the case of Tel Hai, Jabotinsky’s conclusion was “evacuate,” while labor leaders were the ones to preach for resilience. In the case of Philadelphi, as different as it may be, Jabotinsky’s successor (Netanyahu as head of Likud) says “do not evacuate,” and the successors of Ben-Gurion are the ones to call for evacuation (for a deal).

Was Jabotinsky right to call for evacuation, considering what happened just days later, the short battle and its tragic consequences? Was the decision to guard Tel Hai by way of signaling to all future enemies that Jews no longer intend to abandon their reconquered land? These are questions to which there is no definitive answer, not even in retrospect. And I’m afraid the same is true about the question of the Philadelphi corridor and its value for Israel’s security. Supporters and opponents of each policy — sit tight, negotiate, abandon — have their own assessment of risk and opportunity, necessity and choice.

One clear advantage of Jabotinsky and Ben-Gurion compared to the situation we face now is clear and should be noted: Only a few Zionists assumed at the time, or since, that these debating leaders, who often turned to talking about each other cruelly and viciously, would risk the national interest and human lives to advance a political cause or preserve their coalition. Only a few assumed at the time, or since, that their contradicting position was not a principled position. Today we have Benjamin Netanyahu. In his case, justifiable or not, the public is much more cynical and suspicious.

Only a few assumed that Jabotinsky and Ben-Gurion’s contradicting positions were not principled. Today we have Benjamin Netanyahu. In his case, justifiable or not, the public is much more cynical and suspicious.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

As said (see left hand column), most Israelis believe that Netanyahu’s position concerning a hostage deal involves political, coalition-saving, considerations. If that’s true, it ought to be condemned, and yet …

I have no way of knowing what Netanyahu’s real motive is. I only know what position he is presenting. This is a reasoned position. You can accept it, you can reject it. The question of motive is a little less important to me. I mean, if he’s right, I don’t care what the motive is, and if he’s wrong, I don’t care what the motive is. The situation where the motive is important is a situation where, due to nonmaterial reasons, the government insists on a wrong position. Which brings us back to the more important question: Is the position correct?

A week’s numbers

Almost a year of war, almost a year of no change in Israel’s approval of its war leader. Can a country fight a war successfully under a leader in which about 30% have high or somewhat high level of trust?

A reader’s response:

Rob Singer asks: “You wrote a lot about the Haredi draft in the past, but not in recent weeks? Has anything changed?” Answer: No. The Knesset did not legislate, the IDF didn’t get more than a few more recruits. A standstill.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.