A common critique of religion is that it exists only to blunt our fear of death through the deployment of comforting fairytales, replacing life’s great and unsettling unknowns with visions of an afterlife which are — if not less unsettling — at least less unknown.

Such a mindset, however, is foreign to the Torah, which accepts with equanimity that death is a part of life.

Take for example, this unassuming yet breathtaking verse from the opening of the book of Exodus—the second book of the Torah:

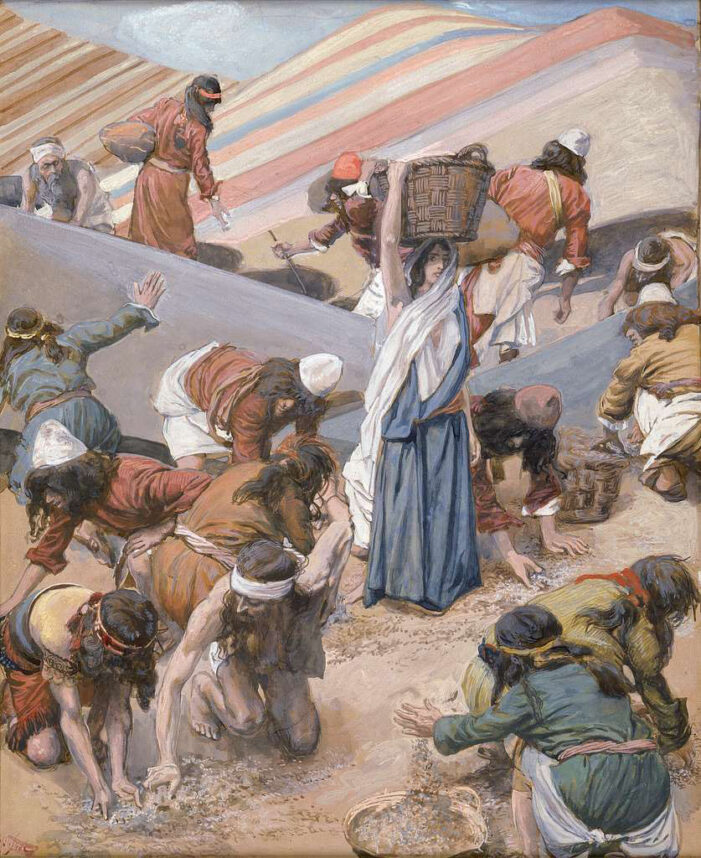

“Joseph died, and all his brothers, and all that generation” (Exodus 1:6).

With this, all of those individuals whose lives, joys, troubles, downfalls, and triumphs constituted the near-singular focus of the book of Genesis have been written out of the text—their time in the spotlight revealed to have been nothing more than a passing trick of the light.

This, however, is the perspective of the narrator. What about the people of the Torah themselves? Well, they may fret about dying without leaving an heir, or perhaps about being buried in alien soil, but death itself—the extinction of individual consciousness and the non-eternality of the human self—does not seem to be a preoccupation of the Biblical consciousness.

Perhaps, as Thomas Mann suggests in his novel “Joseph and His Brothers,” this was because the Biblical man had a more expansive sense of self than we do. When Joseph’s teacher Eliezer would speak, Mann recounts, he related stories from his own past and also from the well of collective memory, never deviating from the use of the first person. His utterance of the word “I” was not “solidly encompassed but, as it were, stood open to the rear, overflowed into earlier times, into areas beyond his own individuality.”

In our own times, the “I” has been sealed. To speak of other lives in the first person is, if not unthinkable, a sign of delusion or deceit. We locate ourselves precisely in this body and lifetime, surrounded on all sides by the oblivion of non-being. It is no wonder that we are afraid.

Moses is the Biblical figure most deeply associated with the fear of death. It is Moses, after all, who is forced by life’s circumstances to be a sealed “I,” cut off from historical continuity by being separated from his people at a young age, cut off from his followers by the need to lead, and cut off from ordinary humanity by his unprecedented closeness with God.

When Moses dies, it is written:

Moses was a hundred and twenty years old when he died; his eyes were undimmed and his vigor unabated. And the Israelites bewailed Moses in the steppes of Moab for thirty days. The period of wailing and mourning for Moses came to an end … Never again did there arise in Israel a prophet like Moses — whom the LORD singled out, face to face, for the various signs and portents that the LORD sent him to display in the land of Egypt, against Pharaoh and all his courtiers and his whole country, and for all the great might and awesome power that Moses displayed before all Israel. (Deuteronomy 34:7-12).

How different a tone is struck in these verses than in Exodus 1:6, when “Joseph died, and all his brothers, and all that generation.”

In the Exodus verse, life ends as a new story begins, giving a sense that death and life comprise one ebb and flow. In Deuteronomy, death is announced at the very conclusion of the entire Torah, giving the sense that death marks an absolute ending.

In Exodus, death is treated with narrative detachment. In Deuteronomy, Moses’ death is treated with sentimentality.

In Exodus, the individual is not separate from the whole — Joseph’s death shares space with the death of his brothers and the whole generation. In Deuteronomy, Moses dies alone.

Moses’ unique relationship with death and identity is also attested to by the words of Psalm 90, the only psalm attributed to Moses himself:

The span of our life is seventy years,

or, given the strength, eighty years;

but the best of them are trouble and sorrow.

They pass by speedily, and we are in darkness. (Psalms 90:10)

In our own day and age, our view of death corresponds more with Deuteronomy and Psalm 90 than with Exodus. We see death as an ending—the sudden cessation of the self, of being. How can we not be terrified?

In our own day and age, our view of death corresponds more with Deuteronomy and Psalm 90 than with Exodus. We see death as an ending—the sudden cessation of the self, of being. How can we not be terrified?

Perhaps we grasp for hope—for a belief in an afterlife, or for some achievement that will be remembered by the world after we have left it. Such things, I fear, are what King Solomon called “hevel,” a puff of wind — vanity.

So long as the “I” is closed — closed to our ancestors and our descendants; closed to the soil and the sky; closed to the Creator and the creation; the world and the void — we will remain afraid. The Torah offers an alternative.

So long as the “I” is closed — closed to our ancestors and our descendants; closed to the soil and the sky; closed to the Creator and the creation; the world and the void — we will remain afraid.

The Torah offers an alternative.

As it is written later in Psalm 90, “Teach us to count our days rightly, that we may obtain a wise heart” (90:12). In other words, let our confrontation with death enlighten us. May learning to “count our days” be that which brings wisdom—the opening of the “I.”

Our liturgy helps us in this pursuit, having us recall our mortality each morning. Whether we are ordinary, mighty, brilliant, or wicked, our deeds and our lives are but “fleeting breath” before God.

The prayer book offers no comforting platitudes to blunt the impact of this statement. Instead, it offers something else: “We are fortunate that we rise early and stay late — morning and evening — and twice daily say: “Hear Israel, the LORD is our God, the LORD is One.”

An acknowledgement of our limitations — our mortality — is paired with a recitation of the Shema, Judaism’s affirmation of the oneness of God, the oneness of all creation, the oneness of all that is.

This, then, is Judaism’s doctrine of life eternal: it is not a place in the clouds but rather the opening of the “I,” the understanding that, in the words of Vietnamese monk Thich Nhat Hanh in his book “No Death, No Fear”: “nothing has a separate self, and nothing exists by itself,” and therefore, “there is no birth, there is no death; there is no coming, there is no going; there is no being, there is no non-being; there is no same, there is no different.”

Matthew Schultz is the author of the essay collection “What Came Before” (2020). He is a rabbinical student at Hebrew College in Newton, Massachusetts.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.