Twenty years have passed, but the moment that drove Rebecca Shwartz to become a pioneering women’s rights lawyer in Jerusalem remains crystalized in her mind.

As a direct result of that one incident, Shwartz today operates Min HaMezar, a growing nonprofit that seeks justice for sexually abused ultra-Orthodox women and girls in Israel.

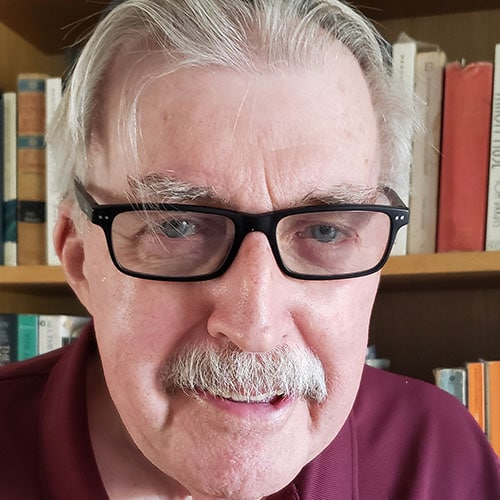

Shwartz, 36, was part of a delegation of 20 Israelis who recently spent a week in Los Angeles on an educational trip sponsored by the Gesher organization and the Israeli government to observe and interact with members of Diaspora communities. A lifelong Charedi, Shwartz said one of the reasons she came to America was to educate, encourage and motivate women who feel powerless — a commitment born one night in 1997.

The summer of that year, when she was 16 years old, she attended a seminary camp with her best friend, also 16.

“Very late one night, my friend told me she had been getting abused for eight years,” Shwartz said. “I was shocked.” The alleged perpetrator was visible in their ultra-Orthodox enclave of B’nai B’rak. “I knew him, too. I asked, ‘How can it be? I didn’t see anything.’ ”

While the Charedi community maintains an insulated existence to shield its members from perceived negative influences of the secular world, Shwartz said she would come to learn that the arrangement works equally to prevent criminal acts, such as sexual abuse, from being reported to authorities.

That night in the camp, as her friend shared her story, “my friend was crying, and I was crying, too,” Shwartz recalled. “I said, ‘I need to do something.’ I didn’t know what, but something.”

Shwartz went home and immediately relayed the revelations to her mother, whose skepticism was typical of the Charedi community. When Shwartz suggested, “Let’s talk to her parents,” her mother dismissed the story.

“My mother was a simple woman 20 years ago,” Shwartz said. “No one knew anything then. My mother said, ‘It can’t be. Your friend must have been dreaming. [Her abuser] is Charedi. He follows the halachah.’ ”

Undeterred, Shwartz urged the victim to tell her parents. “They’ll kill me,” the fearful girl said.

Shwartz assured her friend, “I’ll come with you. Don’t worry.”

However, when the girl’s parents heard her story, they blamed her. “Something must be wrong with you,” Shwartz recalled them telling their daughter. “Maybe you have not been tznius (modest).”

“They sent her away to a school overseas,” Shwartz said. “She was very mad at me. I felt as if I had done a terrible thing.”

The victim fled her Charedi community, permanently. She became secular and has never married.

“I was innocent and very naïve,” Shwartz recalled.

As a result of that experience, Shwartz unofficially launched her career of attempting to persuade abused ultra-Orthodox women and girls — and others — to tell their stories so that the guilty men can be punished.

Shwartz pledged to herself, “When I grow up, I will open a place where girls who can’t talk to anyone will be able to find a solution.”

Her teenage naivete may have been erased in a single night, but there were signs she would choose her own path. The eighth of 11 children, “I always was different,” she said. “I would look out for the poor, for victims no one was paying attention to.”

Married at 19 and soon the mother of two, she was in her mid-20s when she enrolled in a Charedi law school. Outside of classes, Shwartz volunteered at an office that gave legal advice to the poor. When the few religious women who came to the office seeking help were turned away, Shwartz despaired.

“I saw their look,” she said. “They had no one to speak their language. I wanted them to know that I was like them. I sympathized with them.”

“I started to get so many cases that I didn’t know how to handle them. It was amazing.” — Rebecca Shwartz

Employed in the state attorney’s office early in her career, she examined prison files and learned that far more crimes of abuse existed in the Charedi community than she had realized. “When men went away from the community, I thought they were leaving the country,” she said.

No one in the Orthodox media was interested in reporting Shwartz’s discoveries. “I wanted to say to victims, ‘Someone is willing to help you. Please come.’

“I said, ‘OK, I will make pro bono cases.’ I wrote on Facebook, ‘I want to help. It’s free.’ I started to get so many cases that I didn’t know how to handle them. It was amazing.”

A mother of four, she started her own law practice six years ago. Her husband, Manny, is a journalist who posts stories about her cases on the news website where he works.

Despite the response she has received from abused women, Shwartz said she does not believe there is more abuse today than years ago in the Charedi community. The difference, she said, is that the abuse is now being reported.

She said she was heartened by the response she received during her visit to the United States.

“I gave lectures to women from all over the country on women’s empowerment and coping with sexual abuse,” Shwartz said. “There was a tremendous response. Women were eager to hear, to learn, to receive information and to open their hearts.

“All of us, here and in Israel, have one thing in common: To keep our children’s souls healthy in a protected body.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.