One verse, five voices. Edited by Nina Litvak and Salvador Litvak, the Accidental Talmudist

Then God remembered Rachel, and God listened to her and opened her womb. She conceived and bore a son, and said, ‘God has taken away my disgrace.‘

– Gen. 30:22-23

Kylie Ora Lobell

Author of the forthcoming Jewish conversion memoir, “Choosing to be Chosen: From Being an Atheist Non-Jew to an Orthodox Jew” (Wicked Son)

Rachel was supposed to marry Jacob, and Leah was supposed to marry Esau. However, Esau chose a path of wickedness, so Leah cried out to Hashem that she wouldn’t have to marry him. She married Jacob instead, after Rachel agreed to it. Rachel and Jacob were each other’s true loves, but Rachel was a good sister who sacrificed what she wanted. According to Sara Blau of Chabad.org, Rachel also sacrificed her place in the Cave of Machpelah, where Leah and Jacob are buried. She agreed to be buried on the side of the road so that she could comfort the Jews who were exiled following the destruction of the Temple. It is because of her sacrifice that all the Jewish people will return to Israel one day, when Moshiach comes and the Temple is rebuilt.

Today, we are all about comfort and avoiding sacrifice. What I’ve noticed is that when I sacrifice my own comfort – when I go out of my way to do something for others or goes against my ego – I am rewarded. I hate fasting. I do it anyway! Traditional prayer often bores me, but I wake up and try my hardest to say my morning prayers. I’d much rather listen to a gossipy political podcast than a Torah class – but every day, I tune into Rabbi David Bassous’ incredible Torah podcast. When I sacrifice, I’m quieting my animal soul and letting my Godly soul take the lead, just like Rachel did. Let’s all strive to be more like our powerful matriarch and do the same.

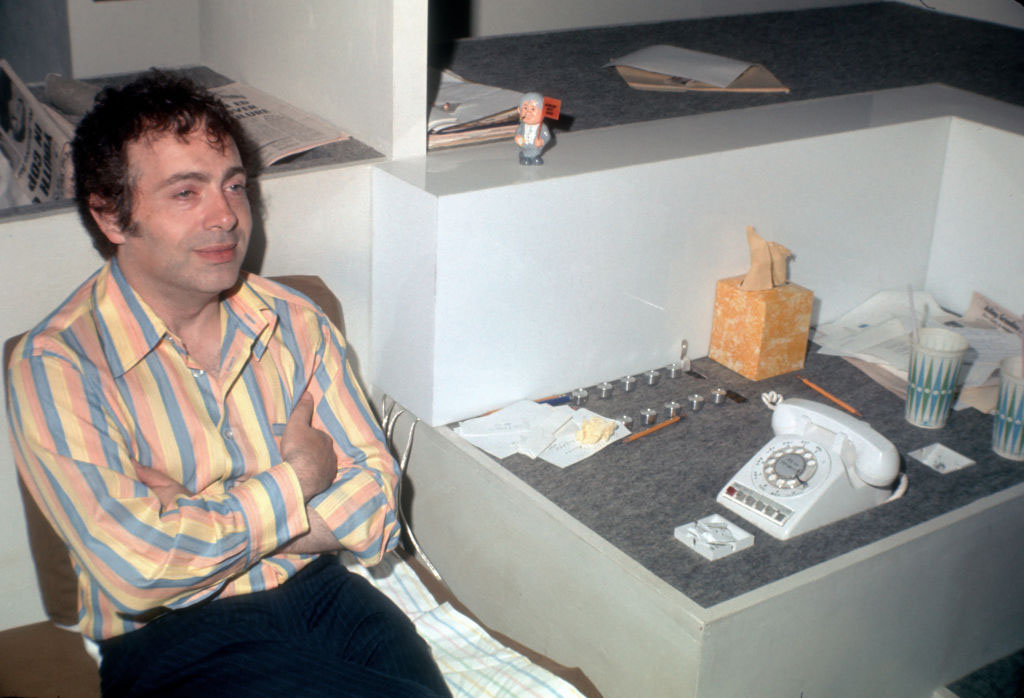

Rabbi Benjamin Blech

Professor of Talmud, Yeshiva University

When Rachel finally conceived … she said, ‘God has taken away my disgrace’” (Gen. 30:23). Rachel’s joy was not only personal; it affirmed a divine calling. In Jewish life, creation is the greatest form of imitatio Dei: God creates a world; we partner by creating a future — most tangibly through children and the mitzvah of “pru u’rvu.” Her shame lifted because her life now extended beyond herself.

By contrast, today many young Americans — Gen Z prominently among them — express hesitation about ever having children. Pew Research Center reports that the share of U.S. adults under 50 without children who say they’re unlikely ever to have kids rose from 37% to 47% between 2018 and 2023. Financial and cultural reasons top the list. Other polling focused on Gen Z and millennials finds nearly one in four childless young adults plan to remain child-free, often citing costs and the state of the world.

Judaism does not dismiss the burdens of parenting; it elevates them. Creating and raising a child is the most everyday way to echo God’s creative act — bringing new image-bearers into being, nurturing wisdom and kindness and linking past to future. When a generation refuses that task, it negates a central command and frays the covenantal chain. If “Z” chose barrenness as an ideal, then — like the letter itself — it would be the end of the line. Rachel teaches the opposite ethic: to welcome life despite fear, to see the home as a small sanctuary and to measure dignity not by convenience but by continuity. Her gratitude is a timeless rebuke to fashionable despair — and a summons to choose creation.

Rabbi Elazar Bergman

Author of the newly released “The Daven Better Handbook”

Our matriarch Rachel, affectionately known here in Jerusalem as Mama Rachel, is an analog for the Oral Torah, i.e., Talmud and Jewish law, Midrash etc. The wisdom of the Oral Torah is the beauty for which she is known (Genesis 29:17) because everyone considers Wisdom, and its study, beautiful.

But even more important than the study of glorious Wisdom is doing the wise deeds born from it (Avot 1:17). One who thinks, even mistakenly, that this study itself is primary, HaShem forbid, is tantamount to being a heretic, a full-fledged villain. Without good deeds, the Torah is worthless, even poisonous.

What HaShem “remembers” about Mama Rachel is her selfless deed. In order to spare her sister Leah shame, she relinquished her future as Mrs. Jacob and allowed her sister Leah that privilege. (Mama Rachel did this by divulging the secret wedding-night signals Jacob had entrusted to her to Leah.)

Such a sacrifice, a deed so costly and magnanimous, produces a Joseph. Joseph was a tzaddik whose private service of HaShem, chastity, propelled him to become a leader, teacher and role model. A tzaddik like that inspires others to do the good deeds they can do. He helps them, us, avoid the shame of a life barren of good deeds. Good Shabbos!

Rabbi Barry J Chesler

Schechter School of Long Island

One can only imagine the growing frustration and diminished self-worth as Rachel watches her sister, her handmaid, and her sister’s handmaid give birth to 11 children while she remains childless. Only after all of these children are born does “God remember her … heed her and open her womb.” When a son is born, she declares, “God has removed my disgrace.”

Rashi tells us that God remembered how Rachel gave Leah the signs which would confirm her identity so that Leah could actually be married first. This act of magnanimity on Rachel’s part, together with Rachel’s despair that her continued infertility will lead Jacob to divorce her, and she would end up with Esau, identified as Esau the Wicked, prompts God to open her womb. Once her son is born, Rachel declares that God has now removed my disgrace. While the Torah seems to suggest that the disgrace is infertility, Rashi suggests that it is the possibility that Rachel will be divorced and end up with Esau that is the disgrace.

For us, living in different times and different lands, the pshat, the plain meaning, seems closer to our truth. Rachel comes to remind us that validation and sense of self comes from within, not from without. In the parsha, Jacob’s professions of love cannot offset Rachel’s infertility; by contrast, Leah’s children at least partially offset the deficiencies in her relationship with Jacob. With both women, that validation is confirmed by God. So may it be with us.

Rabbi Gershon Schusterman

Author, “Why God Why?”

Of the four matriarchs, Jews relate most personally to Rachel. The Torah’s stories about her challenges and triumphs are more elaborate and personal than those of the other matriarchs. Her final chapter was her untimely death as she gave birth to the 12th of Jacob’s sons and her burial at a roadside in Bethlehem and not in the shrine with the other patriarchs and their wives, facts which naturally evoked our pathos and empathy.

When Rachel is finally blessed with a child after many years, she expresses her joy as no longer being “disgraced.” We can understand her pain for not having given birth to a child. But why would she have felt disgraced, when she knew that she was Jacob’s beloved?

The Midrash gives the following insight: In earlier biblical times there was a common practice of marrying two wives: one to bear children and one to serve as the perennially beautiful “trophy wife,” for which purpose she was intentionally sterilized. Rachel, being beautiful and childless, was so considered.

The Torah asserts that “Rachel was beautiful of form and of appearance,” which the Midrash reads as alluding to character and spiritual qualities. While shallow women might revel in the fun that might accompany their skin-deep attractiveness, not Rachel. She was a paragon of kindness and virtue in a crass and deceitful society. To her, being valued for merely her physical beauty was demeaning and disgracing. Now that she has given birth, “God has taken away my disgrace.”