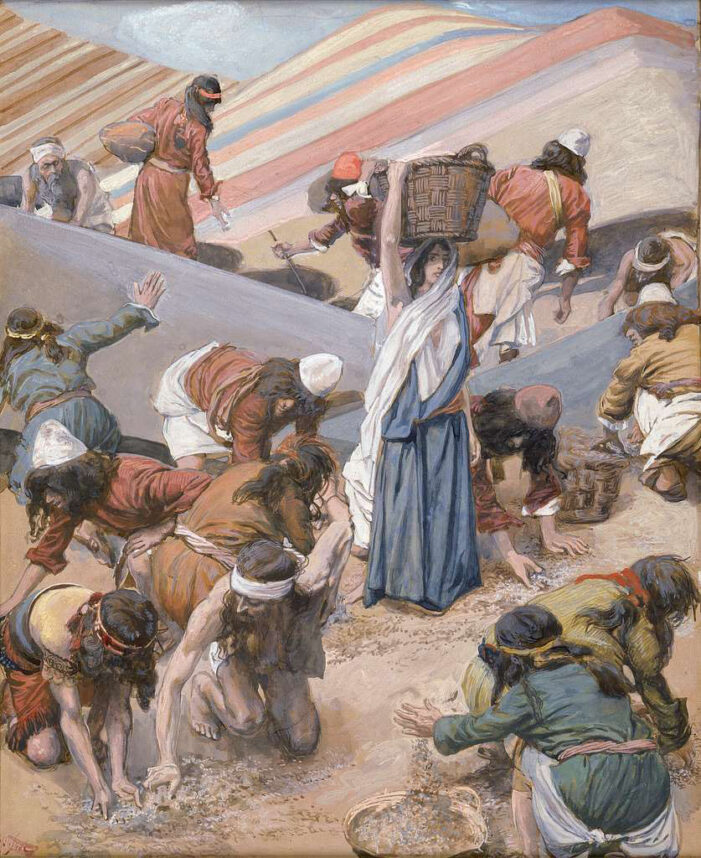

Never before had cleaning off so shaped history. But when an Egyptian princess went to take a quick dip in the Nile, her discovery and rescue of baby Moses in his basket set the Israelites on their path toward that eventual dramatic escape from the shackles of Egypt.

The second chapter of Exodus sets the scene: “The daughter of Pharaoh came down to bathe at the river, while her attendants walked beside the river. She saw the basket among the reeds and sent her maid (amatah) to bring it. When she opened it, she saw the child. He was crying, and she took pity on him. ‘This must be one of the Hebrews’ children,’ she said.”

Miriam, Moses’ sister, having held out hope at the riverbank that somehow her brother might sail past the clutches of Pharaoh’s decree that all male Jewish children be slaughtered, saw what unfolded and helpfully offered to find a nursemaid to suckle the child. That volunteer caretaker she recommended, of course, was secretly Moses’ biological mother, Yocheved. Moses then grew up in the palace of the king but with the spiritual and national mentorship of his Jewish family, uniquely positioning him to lead his people to freedom.

The act of warm-heartedness of this unnamed Egyptian was, ever since, celebrated by the Jewish tradition.

Moses’s rescue-by-princess was depicted on the western wall of the ruins of the ancient synagogue ruins found in Dura-Europos, modern-day Syria, in a rendering dated to the mid-third century C.E. In it, Pharaoh is off to the side, seated on his throne. A scribe next to him writes down the royal commands — no doubt the order to execute babies, the very edict his own daughter disobeys.

Rabbinic texts also parsed every aspect of the brief episode. Why did she need to go bathe, they wondered? Sefer HaYashar suggests a sunburn. God had sent a heatwave, which seared the Egyptians and left them seeking a means of cooling off. Perhaps, came another conjecture, she had that awful skin disease, tzara’at. Thus Shemot Rabbah’s proposal that “Pharaoh’s daughter was a leper; that is why she went to bathe. When she touched the basket she was cured. That is why she had compassion for Moses and loved him exceedingly.”

Pirkei deRebbe Eliezer adds that her sensitive skin required the cold Nile water, as opposed to the warm water of an indoor facility. Her subsequent reward, though unspecified in the Bible itself, was eternal bliss – “Whosoever preserves a life is as though he had kept alive the whole world. Therefore was she worthy to (inherit) the life in this world and the life in the world to come.” Mystical texts record her entering the heavenly realm alive, sitting alongside Elijah and the Messiah.

The Talmud, in turn, senses a sign of her personal fealty to the Jewish cause as an aspiring convert to the faith. “Rabbi Yohanan says in the name of Rabbi Shimon ben Yohai: This teaches that she came down to the river to cleanse herself from the impurity of her father’s idols, as she was immersing herself as part of the conversion process.”

No doubt miracles enabled the shocking rescue. She felt compelled to head to the site because of a dream, offered the first-century work Biblical Antiquities. Other texts add that the princess saw the Divine Presence hovering above Moses. When her maidens tried to convince her not to save him, the angel Gabriel came from heaven and struck them down. Though perhaps it wasn’t a maiden she sent to grab the basket, but rather her arm stretched many cubits (amot) to enable her to grab it.

Another Talmudic tractate gives the anonymous-in-the-Bible heroine a name reflecting her loyalty to Israel’s God. Actually, two names. She was called Bityah (“God’s daughter) or Yehudiyah (“Jewess”).

Was she even Pharaoh’s biological daughter? A surprising Midrash Talpiot argued that she was not. Rather, she and Moses’ future wife Tziporah were Moses’ biological sisters (!). The former was seized by force by the Egyptian king, and the latter by Jethro, Pharaoh’s adviser and Moses’ eventual father-in-law, and raised in their respective homes. (Lest one be shocked that Moses, according to this text, eventually married his sister, the midrash notes that this was permissible prior to Sinai, and Tziporah was uniquely righteous.)

Of course, suggests the Arukh HaShulchan, Pharaoh’s daughter was spared the death of the firstborn — the 10th of those notorious Plagues — in the merit of Moshe, whose life she had saved.

Moses undoubtedly expressed gratitude for the rescue. As the scholar of the Second Temple period Malka Simkovich has noted, Ezekiel the Tragedian, a second- or first-century B.C.E. Jew who lived in Egypt, composed a Greek play whose verses have Moses reminiscing how: “Throughout my boyhood years the princess did, for princely rearing and instruction apt, provide all things, as though I were her own, the circle of the days then being full.”

Simkovich also notes that the second century BCE Book of Jubilees calls Bityah a different name, Thermuthis, as does the historian Josephus. A popular Greek name for Egyptian women at the time, it’s a variation of the Egyptian Renenūtet, the Egyptian goddess of nourishment, from the verb meaning “to nurse or rear,” a fitting appellation for the adoptive figure.

In Josephus’ dramatic detailing, after the extraordinary rescue, she hoped Moses would himself become king: “… one day she brought Moses to her father and showed him to him, and told him how she had been mindful for the succession, were it God’s will to grant her no child of her own, by bringing up a boy of divine beauty and generous spirit, and by what a miracle she had received him of the river’s bounty, ‘and I thought,’ she said, ‘to make him my child and heir to your kingdom.’”

Alas, in playing with his adopted grandson, Pharaoh freaks out. “To please his daughter, [he] placed his diadem upon [Moses’] head. But Moses tore it off and flung it to the ground, in mere childishness, and trampled it underfoot; and this was taken as an omen of evil import to the kingdom.”

When the adult Moses led his people to liberation, Bityah joined her now-fellow Jews and went too. In her old age, she married Caleb, who, alongside Joshua, encouraged the desert-wandering Israelite tribes to ignore the bad report of the spies who had returned from scouting the Promised Land. As the Talmud tells it, “The Holy One, Blessed be He, said: Let Caleb, who rebelled against the advice of the spies, come and marry the daughter of Pharaoh, who rebelled against the idols of her father’s home.”

Modern literary scholars have suggested the princess’ salvation foreshadows God’s own extension of His saving hands to His people. Pharaoh’s daughter’s coming down and seeing a baby crying is mirrored by God’s actions in Exodus’ third chapter, which has Him telling the now adult Moses “I have indeed seen the misery of my people in Egypt. I have heard them crying out … So I have come down to rescue them.”

The bath of Bityah (or Yehudiyah or Thermuthis) then, even without the rabbinic accounts of the many miracles involved in her saving of Moses and subsequent religious conversion, offers a model for those non-palace-dwellers of us to follow. If her dunk to cool off on that hot Egyptian afternoon teaches us anything, it’s that small acts of kindness to the other might very well draw forth God’s salvation for us all.

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include “The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada,” which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, “Esther in America,” “Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth” and “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.