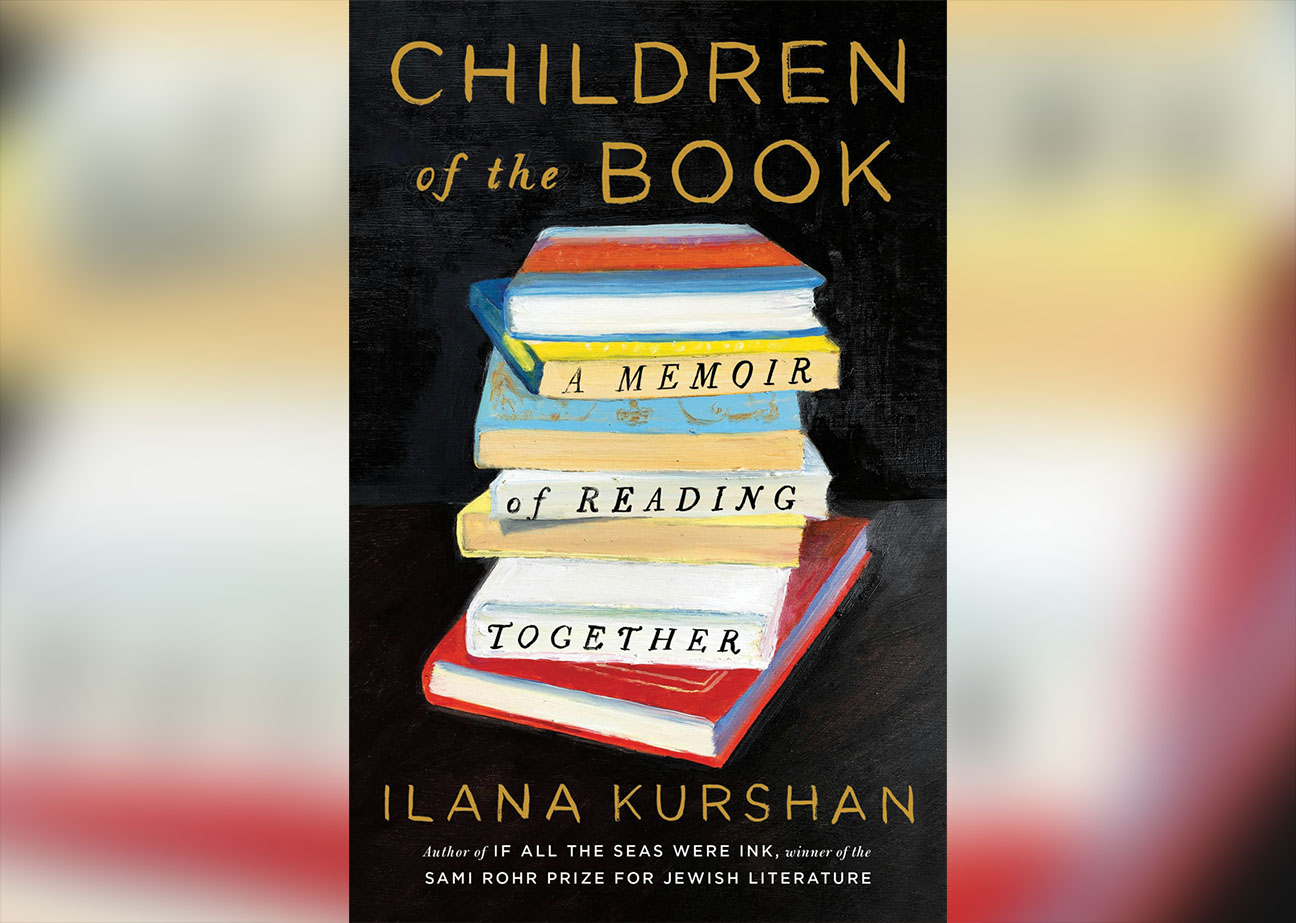

In Ilana Kurshan’s new memoir, “Children of the Book: A Memoir of Reading Together,” the author describes a familiar predicament: A mother with work to do is trapped in her children’s room because they do not want her to leave until they fall asleep. While most parents recognize the frustrations of this struggle, they will likely be less familiar with Kurshan’s solution: She transforms her children’s requests into an opportunity by practicing chanting the weekly Torah portion for synagogue in their rooms, accomplishing a third more ambitious task: “I would like Torah to become the soundtrack for my life. I would like Torah to become the soundtrack for my children’s lives, too.” Throughout the memoir, Kurshan balances her love for Jewish texts and literature with raising her children, but rather than presenting those needs as in tension with one another, she depicts her own development as a Jewish woman with a career in tune with motherhood. Preparing for Shabbat services while dealing with her children’s needs does not hamper her parenting; it miraculously harmonizes with it. In reading with her children, to her children, or surrounded by her children, Kurshan depicts and models the rhythm of a richly Jewish textual life.

Kurshan’s memoir demonstrates how the annual Jewish liturgical cycle of Torah reading synchronizes with raising a family, enabling the author and mother to simultaneously better understand the Torah’s wisdom from week to week and the brilliance of her children as they weave their Torah learning into their daily lives. Working as a skilled translator and a prominent Jewish educator in addition to being a parent adds additional responsibilities to her plate. Yet the porousness of the boundaries between secular and Jewish texts and lived experiences and literary experiences enables Kurshan to see how religious texts can shape and develop the religious life and vice versa: “The more we read together, the more I come to know my children. And the better I am at reading them.”

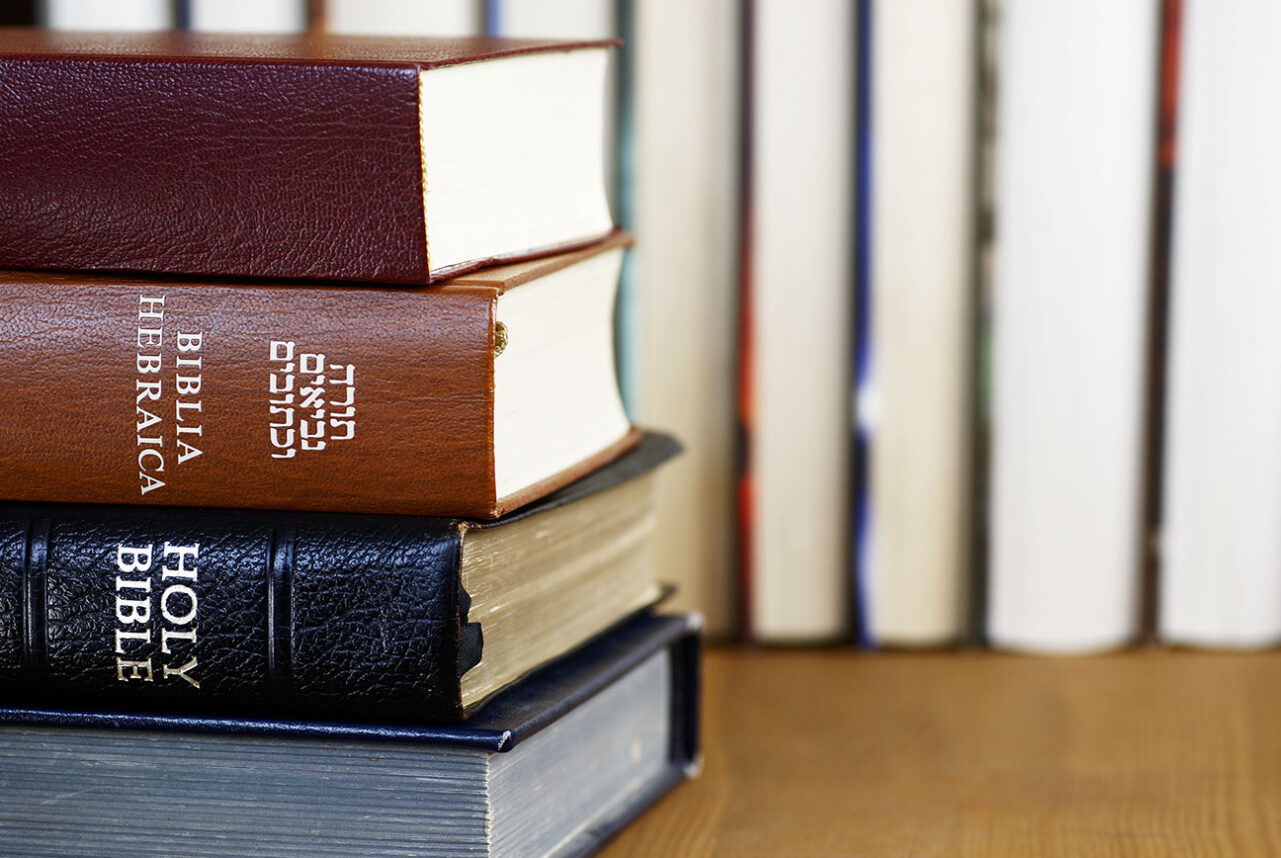

Categorizing “Children of the Book” can be complex. Kurshan’s first memoir, “If All the Seas Were Ink,” won a National Jewish Book Award and described her experiences of marriage and divorce through her daily study of the Talmud. While it was organized by the tractates that Kurshan was reading and how those tractates bled into her lived experiences, “Children of the Book” is organized by the five books of the Torah and each of its sections and sub-sections can be savored slowly along with the weekly Torah portion. The text is a bibliomemoir because it traces the author’s life through the literature they read, yet it is unique because bibliomemoirs usually focus on how the reading experience of a single text shapes an author’s life. Though the memoir describes how Torah portions become the literary backdrop for all of Kurshan’s reading, writing and lived experiences, “Children of the Book” overflows with intertextuality and Kurshan’s love for all texts so that the Torah reshapes what secular and religious texts mean for Kurshan while the books she reads reframe her understanding of the weekly Torah portion. In Kurshan’s life, wisdom does not flow in a single direction but circulates freely, so that sometimes her children help her read the Torah, and at other times it is the Torah that helps her read her children.

Since this is a book about reading with and around children, it is a boon for readers who think about the role of reading in a parent-child relationship. Reading selective subsections asynchronously supports someone trying to find a work-life balance. I chose to take a page both literally and metaphorically from Kurshan’s playbook and found success in reading this book about reading to her own children. Reading Kurshan’s parsha-inflected tales with my kids helped them relate our bedtime stories and weekly parsha discussions to their own lives.

When Kurshan describes how literature uses foreshadowing, for example, she relates the practice to both her family’s experience of living through the unknown period of the coronavirus and the biblical Israelite experience in the desert. Reflecting on her children’s boredom and restlessness during the pandemic and the unknown, she recalls, “I thought about God’s pledge to bring the Israelites to a land ‘flowing with milk and honey’ (Numbers 14:8), and realized that every divine promise is a spoiler of sorts. With so much uncertainty around us, I was relieved that I could promise my children that at least in the book we were reading, it would all turn out OK.” Of course, Kurshan also weaves in a secular children’s book by connecting Beverly Cleary’s Ramona’s complaints to her children’s complaints and the Israelites’ kvetching, weighing the benefits and pitfalls of knowing what is coming in a story and in life. But she also uses the Torah and children’s literature as guides—texts that provide “spoilers” for our twenty-first-century lived experiences—so that, even amid an unprecedented modern-day pandemic, one does not have to feel as though the literary past has no guidance to offer our contemporary moment.

After reading Kurshan, I started paying attention not just to what I read to my children, but how I read to and with them. I began slowing down and did not rush my five-year-old son when he made me pause my reading of Cary Fagan’s “Mr. Zinger’s Hat” to ask me if any of his hats would also have stories buried in them. I was just trying to get him to bed so that I could get some work done, but “Children of the Book” reminded me that there are stories buried everywhere around us, and if we don’t slow down to unearth them with our children, we are missing out on connecting both to texts and to our kids. Although I still put my son right to bed, when he woke up the next morning, we immediately searched his hats.

Na’amit Sturm Nagel is a doctoral candidate in the English department at UC Irvine.