Settler colonialism has expanded beyond Earth’s atmosphere. So claimed geography professors Katherine Sammler and Casey Lynch in a 2021 paper negatively reacting to plans to build an observatory on Mauna Kea, an inactive Hawaiian volcano. “Scientific ‘objectivity,” they argued, as well as categories such as “space, time, and matter” are artifacts of Western imperialism. Trying to study such matters, they decried, ignores that time and space are political constructs imposed on indigenous people as a demonstration of power.

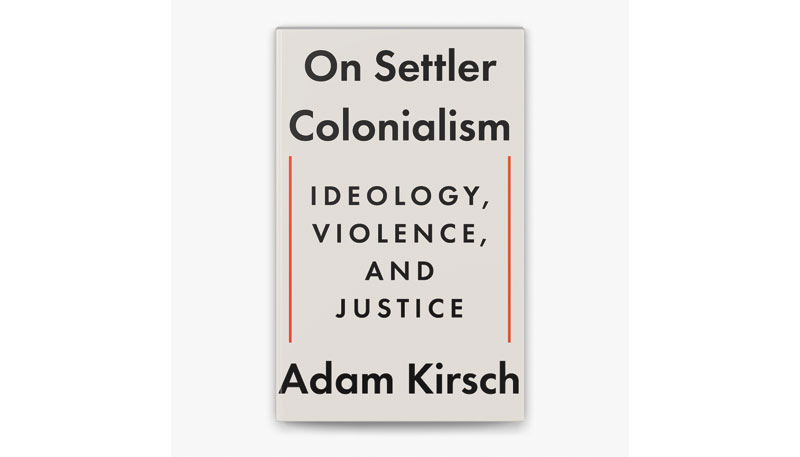

Adam Kirsch’s must-read “On Settler Colonialism: Ideology, Violence, and Justice” seeks to understand, and argue against, this morally dangerous framework that has appeared in contexts ranging from climate change to the Israel-Hamas war.

In the book, expanding upon an essay he wrote for The Wall Street Journal — where he serves as an editor — shortly after Oct. 7, Kirsch explains that, put simply, describing countries like the United States and Israel “as settler colonial societies is a way of arguing that they are permanently illegitimate, because they were created against the will of the people previously living there — Native Americans and Palestinian Arabs.” This framework leads people “who think of themselves as idealists into morally dangerous territory, in ways that are all too familiar in modern history.”

Describing countries like the United States and Israel “as settler colonial societies” leads people “who think of themselves as idealists into morally dangerous territory, in ways that are all too familiar in modern history.”

Thus, an academic theory popularized in recent decades ends up claiming, in representative samples like a primer he cites from the Southern Poverty Law Center, that “all non-Indigenous people are settler-colonizers whether they were born here or not.” (To gauge if this passes the sniff test, try to imagine how your great-grandfather, a dirt-poor German Jewish immigrant in New York’s Lower East Side circa 1890, would react as he pushed his dry goods cart hoping to make a sale in his broken English if he was told he was a white colonial oppressor.)

The concept is so fertile, Kirsch argues, because it offers a one-size-fits-all theory of original sin and subsequent purification. Thus guides have emerged on decolonizing your diet, your backyard, your bookshelf and your corporate board, relegating anything deemed negative to destruction.

How one might decolonize a country is, he points out, difficult to picture in practice, an inconvenient fact for those who decry colonialist activity. Do the tenured academic theorists imagine the U.S. should deport the 97% of its non-Native 340 million residents?

But thankfully for these well-credentialed idealists, there’s Israel. “On Oct. 7 Hamas did more than imagine it. By killing old people and children inside the borders of Israel, it acted on the principle that every citizen of a settler colonial state is a fair target, because none of them has a right to be there. For many critics of settler colonialism whose opposition consisted merely of theory and invective, this highly concrete [example] … was — as one Cornell professor told a student rally — ‘exhilarating’ and ‘energizing.’” It was a theory made manifest — mind you, in murder, but, one presumes, that would just be relegated to an academic footnote.

Originally, “settler colonialism” was applied to empires and colonies, where a small, white population dominated a vastly larger population of natives — think the U.K. in India circa 100 years ago. The shift then occurred whereby it was used in Australia, Canada and the U.S., where “people do not think of themselves as settlers, because they have taken over the land so successfully that they see themselves as natives.”

Kirsch notes multiple flaws in the framework, in both its original and more recent iterations. “If the definition of a progressive movement is that it believes the future can be better than the past,” he writes, “then the ideology of settler colonialism is not progressive, because it believes the past was better than the future.”

He also notes that cultural pluralism, otherwise known as multiculturalism, emerged as a liberal alternative to the more conservative value of assimilation. As Horace Kallen articulated it in a 1915 essay “Democracy Versus the Melting Pot,” the US should imagine itself as an orchestra, in which every culture’s unique timbre contributes to the symphony’s beautiful sounds, not a monoculture devoid of difference. Alas, as Kirsch puts it, “from the perspective of settler colonialism, Native Americans aren’t just an instrument in the orchestra; they are more like the rightful owners of the land on which the concert hall stands. To do justice would mean putting the orchestra out of business.”

Many technological advances have emerged from non-Natives. Should those be somehow dialed back? Should billions of humans decide to relinquish cars, electricity and cheap consumer goods produced by extracting natural resources left untouched by the original denizens? Would we be better off? Would the environment? (As Kirsch documents, Vietnam, which liberated itself from French and American control, tripled its CO2 emissions in the past decade.)

Shifting his focus back to Israel, Kirsch helpfully notes that the characteristics of the theory don’t actually apply. Unlike European settlers who expanded over a continent, destroying indigenous people and cultures in their wake, modern Zionism emerged as Palestine was a province of the Ottoman Empire, and later Britain. Jews settled there only by permission and had no recourse when immigration was curtailed. The country is roughly the size of New Jersey, surrounded by 22 Arab countries in the rest of the Middle East. The population growth in Gaza and the West Bank despite population displacement during the 1948 war; the Arab doctors, Supreme Court justices and countless Arabic street signs in Israel: “the persistence of the conflict in Israel-Palestine is due precisely to the coexistence of two peoples in the same land — as opposed to the classic sites of settler colonialism, where the conflict between European settlers and native peoples ended with the destruction of the latter.”

Additionally and fundamentally, of course, the Jews were native to the land millennia before the rise of Islam. Returning to our homeland was an unfulfilled prayer for a hundred generations. “Recognizing Jews as aboriginal to the land of Israel would turn one of settler colonial studies’ key rhetorical weapons against itself,” so its proponents decline to engage with this well-documented fact and its implications.

“As far back as we can see, there is no terra nullius [territory without a master] and no true indigeneity. Every people that occupies a territory took it from another people, who took it from someone else.”

Kirsch concludes by stating what is obvious but unfortunately too often ignored. Every nation has its flaws and its challenges. “There is not a single country whose history does not provoke horror, if seen through the eyes of the victims rather than the victors.” While that is no doubt tragic, it is part of the messiness of life. “As far back as we can see, there is no terra nullius [territory without a master] and no true indigeneity. Every people that occupies a territory took it from another people, who took it from someone else.” While reality might not ring of ultimate justice, the “past can’t be rectified so easily, because history cannot stop and restart.” Instead, we must recognize that “the wounds we inherit can’t be undone.” All we can do is try to navigate the messiness of the future together in a spirit of healing, even as scars remain.

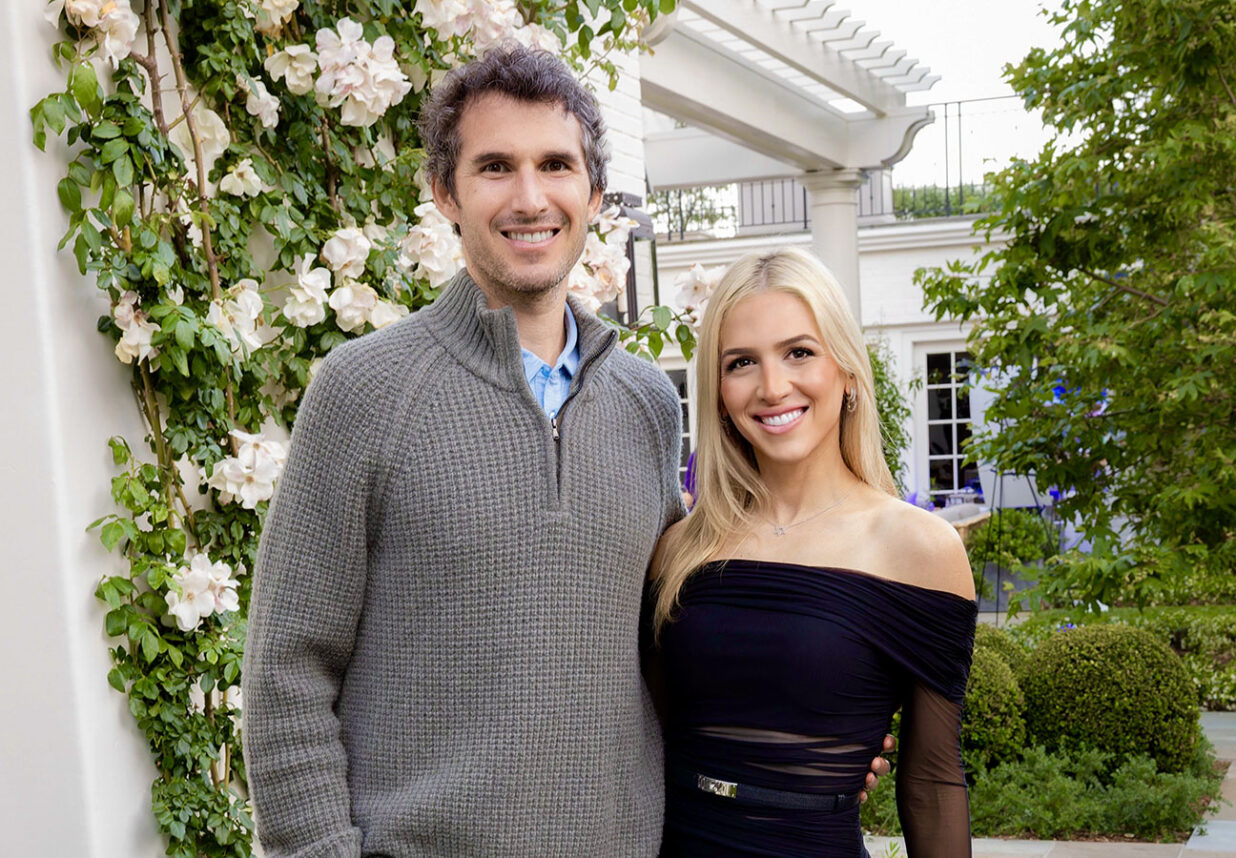

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include “The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada,” which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, “Esther in America,” “Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth” and “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.”