“If we’re only relying on written history, what stories do we miss?” our Yemenite protagonist, Zohara, asks her Ashky husband, Zack. “What happens to the stories of people who were illiterate? To marginalized communities?” Zohara has important questions. She wants to know “whose stories are written in history books? And who decides which stories to include?”

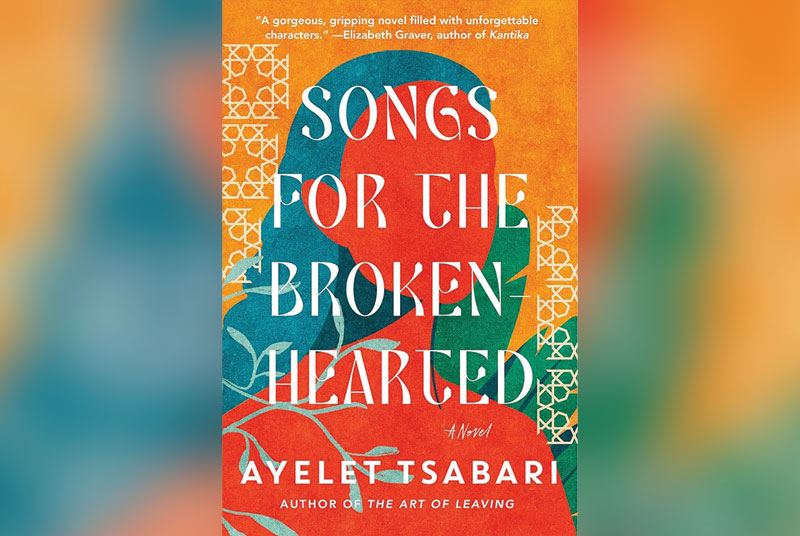

These are not new questions; they are the questions that have formed the basis for a groundswell of literature that has emerged since the 1960s, literature that has challenged History (with a capital H) and historical ways of knowing. Yet, every story in this groundswell is different. Each insists on its own imagining, its own visions and revisions of those told before. All are important. When we are lucky, these new stories are masterfully written, gripping, beautiful, tender, complicated—like Ayelet Tsabari’s debut novel, “Songs for the Brokenhearted.”

I’ve been fangirling Tsabari since her publication, more than ten years ago, of “The Best Place on Earth,” a short story collection that won numerous prizes. Her 2019 memoir, “The Art of Leaving” was equally superb. I still think, a lot, about her chapter on Ofra Haza, a compelling and thoughtful examination of racism against Mizrahim in Israel. I suppose this racism was something I already knew a little about. I knew that when people asked where my father was from and I replied “Bat Yam,” I could expect snickers, and I knew, too, that the big gold jewelry he wore was embarrassing. I knew that “Lehiot Ita,” a bourekas-style Israeli television series, tellingly called “Baker and the Beauty” in English, pulled its laughs from the ridiculous pairing of working-class, dark-skinned, Yemenite Amos Dahari (Aviv Alush) with super rich supermodel blonde Noa Hollander (Rotem Sela). And maybe somewhere in my mind, I also knew that Ofra Haza’s famous song “Ani Freha” said something about the country’s attitudes toward Mizrahi women. A freha, after all, is not just a ditz; she’s a big-haired, big-earringed, tight-skirted, heavy-makeup-wearing Mizrahi ditz. A freha is poor Vanessa Maimon, Amos’s Moroccan ex-girlfriend on “Baker and the Beauty,” who is made up to embody the racial slur, and for whose character Haza’s album “Hot House” is the soundtrack. Skillfully entwining her own story with Haza’s, Tsabari had readers of her memoir think about whether Haza had internalized racism against Mizrahim or was subverting it, whether she ever wanted to sing a song about being a freha or not, how she cleared a path for other Mizrahi artists (including, we might note, Tsabari).

“Songs for the Brokenhearted,” Tsabari’s first novel, was worth the wait. While Tsabari returns to many of the same themes explored in “The Best Place on Earth” and “The Art of Leaving,” she does so in this sustained work of fiction through a series of fleshed-out characters: Zohara, closest in age (if a decade older) and life story to the author; Yoni, Zohara’s nephew; and Yaqub, the paramour of yore of Zohara’s mother, Saida. All the characters are lost in one way or another, unable to see how they fit into the world around them. Zohara is recently divorced and newly orphaned, Yoni is struggling with the death of his grandmother and lured by political fanatics, and Yaqub loves a married woman.

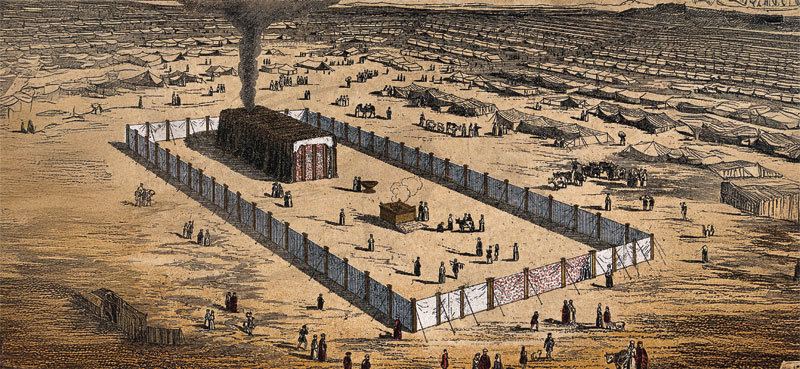

The story shifts among the three points of view, though the only first-person narration is Zohara’s, the dominant voice. It shuttles readers between two moments in time: the lead-up to Yitzhak Rabin’s assassination in 1995 and the arrival of Yemenites in Operation “On Wings of Eagles” to Mahane Olim Rosh HaAyin in 1950. Tracking these two moments, Tsabari is informative almost to the point of didacticism. She writes about the dire conditions in the immigrant camps; the Yemenite Children Affair; the Orphans’ Decree; polygamy; racism against Yemenites and Mizrahim more widely; shadism (also known as colorism) within the Yemenite community; the aftermath of the Oslo Peace Accords; the rise of Mizrahi scholarship; and, perhaps most fascinatingly, the incredible, collaborative tradition of Yemenite women’s songs, or “the stories of people who were illiterate” but still wanted to share their experiences, artfully, for generations to come. Bringing the reader completely into her world, Tsabari weaves Hebrew and Arabic words into the English-language book—makolet, ma’abarot, lahuh. I stumbled on the word “mishtaknezet” and texted an Israeli friend to ask its meaning. She answered, “to become more urbane, sophisticated.” And then I caught the root: Ashkenaz. To become more Ashkenazi. Of course.

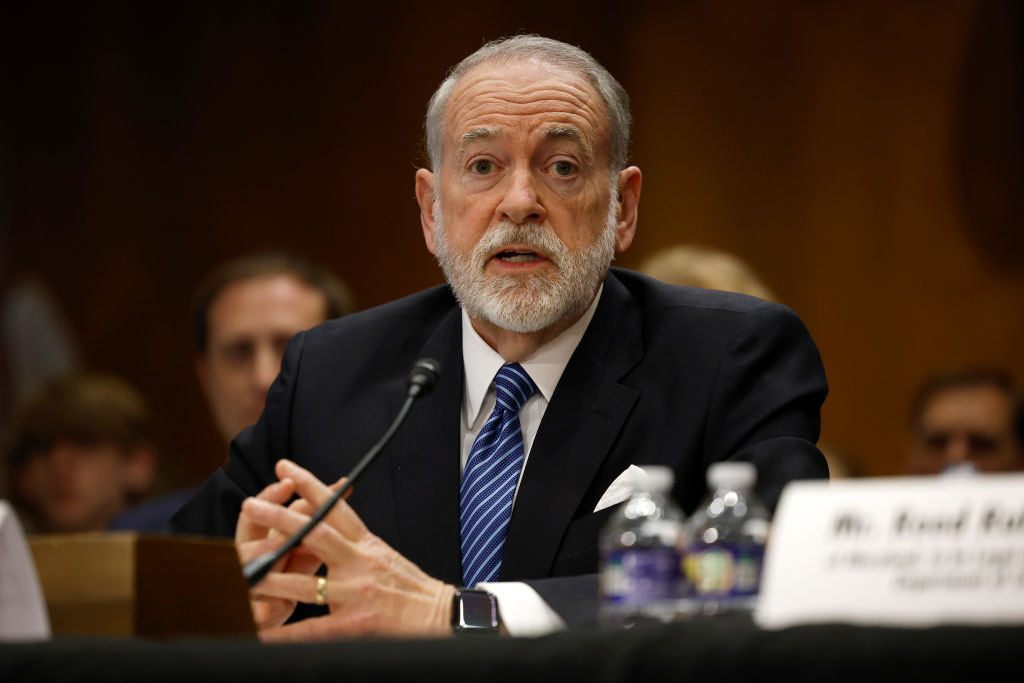

Despite neither time period of the novel being the present, we see how the long tail of the beastly past endures. At a rally Yoni attends, a young guy “pulled the hood ornament off Rabin’s car … He held it up and said it proves they can get to Rabin just as easily.” Tsabari doesn’t name the young man, but it’s impossible not to clock that the man is today’s Minister of National Security, Itamar Ben-Gvir.

Despite neither time period of the novel being the present, we see how the long tail of the beastly past endures.

“Songs for the Brokenhearted” does more than inform; it also explores relationships deeply and achingly. There are multiple romantic relationships in the novel, but the relationships that fuel the narrative are familial ones between women: mother and daughter, mother and sister. These feel painfully real. Tsabari knows what it means to love but not understand someone—which is exactly what such familial relationships are so often like. Because how do we see someone for who they are, as a whole human, when we are pressed up so close to them? Only when she’s cleaning her dead mother’s house, following a trail made of old papers and recorded songs, can Zohara begin to make sense of the woman whom she looked down upon for being illiterate and superstitious and resented for having shipped her off to boarding school. And only then can she find some peace in her own life.

Like the protagonist Zohara, who decides to change her PhD dissertation topic from Eastern European poets to Yemenite women singers, I have found myself increasingly drawn to the lesser-known Jewish stories, like those of immigrants and descendants of Yemen. I’m grateful to Tsabari for telling these stories in a way that is captivating, moving, and lyrical—a song for our time.

Karen Skinazi, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of “Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.