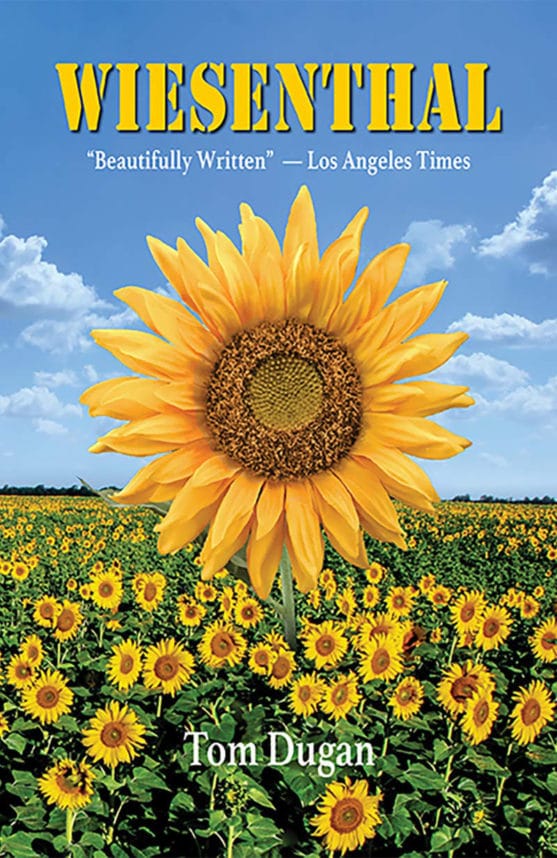

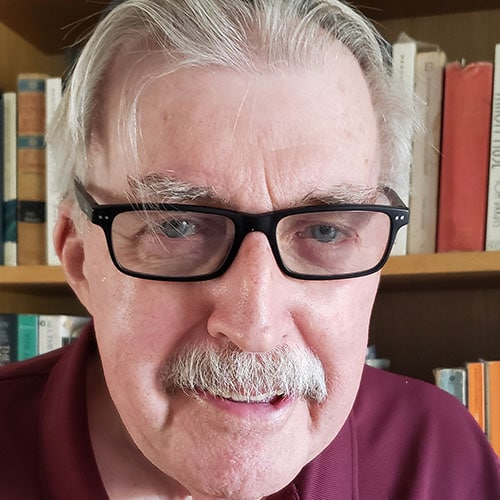

As nightfall approached, an airy, modest-sized space at the Skirball Cultural Center formed an ideal quiet setting last Monday for playwright and actor Tom Dugan to introduce his new book, “Wiesenthal,” to a cozy, invitation-only crowd.

Simon Wiesenthal, history’s most successful pursuer of Nazis, bringing almost 1,100 criminals to justice, lives again in Dugan’s talented hands. “Wiesenthal” is based on the one-man play Dugan has been performing around the world since 2009 at the Torrance Cultural Center.

To quote the book: “Wiesenthal was a Polish Jewish Holocaust survivor, Nazi hunter and writer. After World War II, he dedicated his life to the search for and legal prosecution of Nazi criminals, and to the promotion of Holocaust memory and education.”

Sixteen years after Wiesenthal’s death at the age of 96, his unprecedented accomplishments, reminding Jews and non-Jews about the Holocaust more than a thousand times, are polished to a brilliant gloss by Dugan.

Secondarily, the drama behind the curtains—how a nice Irish Catholic boy from New Jersey came to bring a broad, intense focus to a modern-day Jewish hero—is also fascinating.

“Writing about Wiesenthal resonated with me,” Dugan said, “because of the important lessons my father taught me and also because my wife, Amy, and our two boys, Eli and Miles, are Jewish.

“My father’s generation did a great job of passing down to my generation the valuable lessons of the Holocaust. It was incumbent on me to pass those lessons to later generations. Writing and performing ‘Wiesenthal’ is my way of doing that.”

Dugan’s father, a World War II veteran, “was a liberator,” the author said. “I have always had the idea of honoring his participation in the war. When Wiesenthal passed away in 2005, I immediately started asking people, ‘Would you see a play about Simon Wiesenthal?’ The answer was ‘yes’ in every case. So I figured I had something.”

Dugan writes that “tolerance plays a big part in my life. Teaching the value of tolerance was, I believe, Simon Wiesenthal’s greatest achievement.”

“Wiesenthal” is a photo-laden volume enhanced by a study guide and questions that can serve as educational tools for teachers and students.

Not that this happened overnight. Two years of research and one year of writing built the script. The book was published by Deborah Herman of Bashert Books, Stockbridge, Mass.

Herman, Dugan’s collaborator, told the Journal she fell in love with “Wiesenthal” the play shortly after it debuted off-Broadway in November 2014. “After the play, I told Tom ‘If you ever want to do a book, call me,’” she said.

“Hopped right on it,” cracked the witty 60-year-old Woodland Hills-based Dugan, standing nearby. “Called her five years later,” in 2019, not long before COVID-19 exploded. Throughout the pandemic, Herman and Dugan spent their Southern California-to-Massachusetts days on Zoom. “I am so impressed by his attention to detail,” Herman says.

Dugan was asked about areas of Wiesenthal’s legacy that should be known but are not.

“His entire career was about the future, not the past,” he said, “how the lessons we have learned from the Holocaust must be applied today.

“His entire career was about the future, not the past,” he said, “how the lessons we have learned from the Holocaust must be applied today.

“The most important message is that people cannot understand the evil that the Nazis represented until they can recognize the potential for evil in themselves. That is tough for people to swallow.”

Dugan said teaching was a crucial Wiesenthal contribution to society. “Nazi hunting was heroic and necessary,” he acknowledged. “But as a teacher of the psychology of man, and of sociology, that was Wiesenthal’s most valuable legacy. He broke down how these things could have happened in an understandable, human way that the masses can wrap their head around in present times.”

Wiesenthal talked about “the human savage,” Dugan said. “I have seen a lot of people in the audience going ‘ohhh, ohhh.’ When Wiesenthal said we must recognize the human savage in ourselves, that’s a tough pill to swallow. People get very offended. ‘There is nothing in me that would be in a Nazi,’ they say. ‘Nazis are monsters.’

“My answer is, ‘Monsters are make-believe. Nazis were real. They were human beings.’

“People don’t like to hear that. The danger is that if you make the Nazis like vampires, there is no danger there. The savage inside of us is very real. Unless you look at it and understand it, you might be moved by it.”

Herman, the publisher, said that what she loves “about this project is that while Jews may be the canaries in the coal mine, we are just a sign things are getting tough. This can happen to any marginalized, disenfranchised group. We have seen so much since the pandemic began.”

Cutting to the heart of his work, “this is why Wiesenthal was quite specific,” said Dugan. “His story was not a Jewish story, it was a human story.”

“Wiesenthal” is available in bookstores. For bulk discounts for educational institutions, museums, libraries and book clubs, contact deborah@ micropublishingmedia.com

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.