“Spiritual Surgery: A Journey of Healing Mind, Body and Spirit” by Eva Robbins draws on all of her skills, experiences and roles in life. Robbins is both the cantor and a rabbi at N’vay Shalom synagogue (which she co-founded with her spouse, Rabbi Stephen Robbins), a teacher of meditation and a fine artist.

“Through words, spiritual practice music and art, I knew there was a fundamental connection to healing in Judaism,” declares Robbins, who yearned “to weave spiritual yearning with creative energy,” a process of “repair and mending” that she calls “spiritual surgery.”

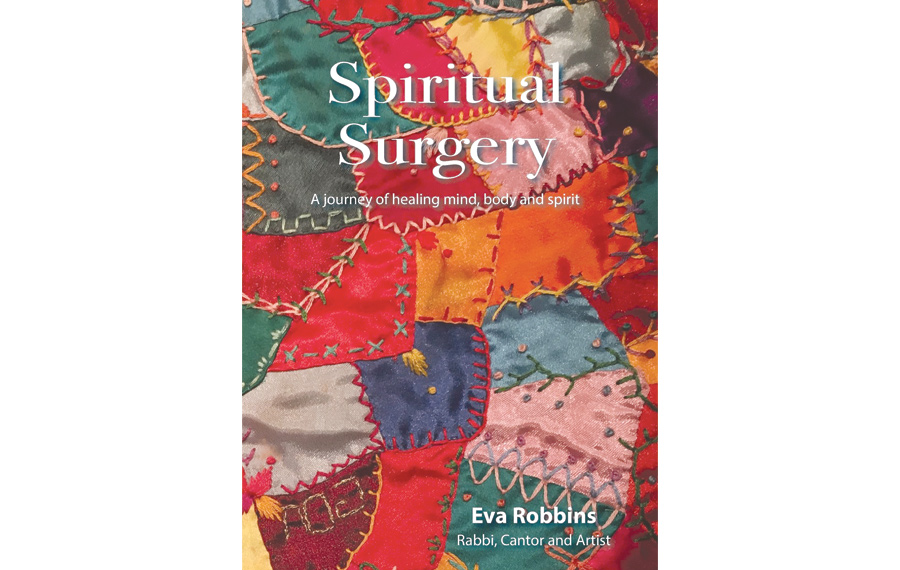

The carefully chosen words in the mission statement for her book, which is published by the author and available on Amazon.com, allow us to see what matters most to Robbins. Another clue is found on the cover of the book — a detail from a work of hand-stitched textile art fashioned by the author herself. Just as a surgeon uses needle and thread to close an incision, Robbins seeks to do something similar for the heart and soul.

Thus does Robbins prepare us for the many-faceted jewel that is the core of her book — an extraordinarily rich and well-informed contemplation of the Mishkan, the tent-like mobile sanctuary that is described and discussed in no less than 13 of the 40 chapters of the Book of Exodus. “Torah presents one chapter on the creation of the world, which is to be a home for humankind,” she points out, “while it dedicates thirteen chapters to the creation of the Mishkan, which is to be a home for God.”

Her artist’s eye enables Robbins to perceive the Mishkan as a physical object, and she wants to know what it was made of and how it was assembled. “It was a large oblong structure with three central areas, consisting of fifteen different materials,” the author explains. “It boggles the mind that such a structure was put together and taken apart on a regular basis as the Israelites traveled through the desert, not to mention the sheer weight of all the metals, fabrics, woods and skins that were carried and used.”

Eva Robbins looks beyond the “simple or literal,” as she puts it, and seeks to find the “interpretative, metaphorical, psycho-spiritual … secret or mystical” meanings of the Mishkan.

Drawing on the specifications that we find in the Torah, Robbins offers a site plan of the Mishkan, complete with linear measurements and placement of the Ark, the altars, the menorah, the bread table and the water basin. She provides a list of building materials — gold, silver, copper, bronze and wood — and the furnishings and tools that were used inside the Mishkan: tables, lampstands, pails, scrapers, basins, flesh hooks and fire pans. As a

textile artist, she pays special attention to “the fabric hangings of fine twisted linen in an open weave pattern” and the

screen fashioned of “blue, purple and crimson wool.”

But she also looks beyond the “simple or literal,” as she puts it, and seeks to find the “interpretative, metaphorical, psycho-spiritual … secret or mystical” meanings of the Mishkan. Expertly reviewing the writings of the commentators — ancient, medieval and contemporary — she considers both the practical uses and the higher symbolism of the structure. Ramban regarded the Mishkan as “the place where sacrifices are to be offered and the perpetual fire is to burn.” Avivah Zornberg suggests that the divine command to build the Mishkan was a test of Israel’s repentance for the sin of worshipping the Golden Calf.

Drawing on the work of Mircea Eliade, Robbins sees a commonality between the Mishkan and all sacred sanctuaries in the ancient world, each of which was “a place … for cultic observance where space and ritual intersected.” The Mishkan and all that it contained, she writes, “created a ‘world in miniature,’ a universe encompassing all the many facets of Divine grace, becoming that ‘axis mundi’ where heaven and earth touched and God and man embraced.”

For Robbins, however, another explanation stands out.

“[I] believe the Mishkan was a necessary healing instrument,” she affirms. “Living and working in the dark and painful environment in Egypt created an empty space, bereft of beauty and grace.” The experience of the Israelites in the Sinai, where God manifested as thunder and lightning, was terrifying: “Sinai was like plugging into a nuclear power plant — it felt as if their lives could be destroyed.” By contrast, “[t]he Mishkan would provide, among other things, a new path, a transformative experience, bringing light, glowing color, beauty and sanctity into their lives.”

A secular reader might wonder if the Mishkan as it is described in the Torah ever actually existed. Robbins herself does not go there. But she readily acknowledges that both the Mishkan and the Temple in Jerusalem are now long gone, and she insists that the biblical account provided Judaism with divine guidance on how to replace both of them.

“The irony is that God uses the words Chochmat Lev, heart of wisdom, as the essential requirement for the building of the Mishkan, whose main focus was the Sacrificial Cult,” she writes, “which would morph into a religion based on the true essence of what these words would come to represent — deep understanding, Torah and prayer.”

Or, as Robbins puts it in her own authentic words: “We were created to create,” she concludes. “Creativity, in all of its many forms, has the potential to open a pathway to wholeness and healing.” Exactly here we find the author’s most accurate and precise definition of the phrase that she uses as a title for a book that is both wise and enchanting.

Jonathan Kirsch, attorney and author, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.