On a cloudy afternoon in Hollywood, Paul and Chris Weitz arerecounting how their late father, legendary fashion designer John Weitz,dressed down a man who dissed their raunchy comedy, “American Pie.”

The elder Weitz had laughed hysterically throughout ascreening of the 1999 film, best known for a scene involving a libidinousteenager and a pastry.

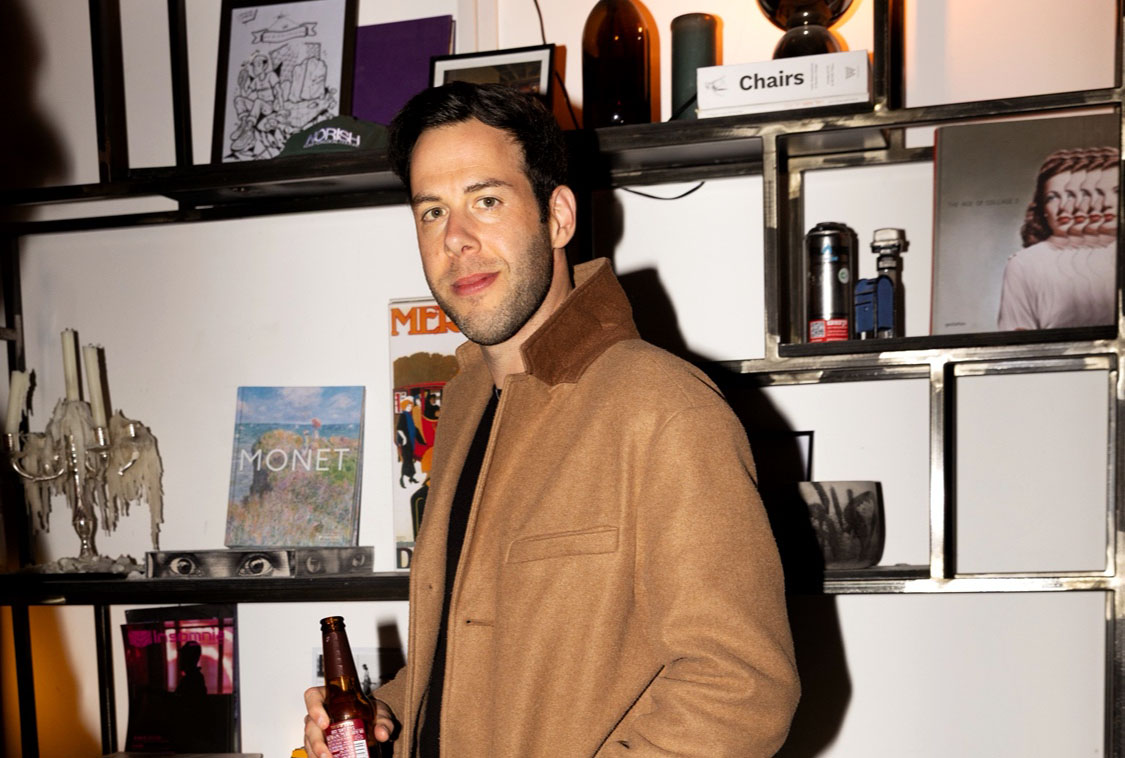

“The next day, an elderly gentleman approached dad in adiner,” says Paul, 37, sprawled in a fuzzy beanbag chair in the brothers’rambling offices.

“He said the movie was vulgar,” adds Chris, 33, who, likehis brother, is dressed in rumpled jeans. “And our father, who was always quickto accept a challenge, even in his 70s, said, ‘Haven’t you ever masturbated inyour life?'”

A photograph of the impeccably groomed pere Weitz dominatesa corner of the casually messy office; father figures loom large, as well, inthe brothers’ comic films. In “Pie,” a well-meaning but dorky dad (Eugene Levy)mortifies his son with overly candid talks about sex. In “About a Boy,” basedon Nick Hornby’s novel, Hugh Grant plays a selfish London bachelor who becomessurrogate father to a bullied, misfit kid.

John Weitz wasn’t required to defend “Boy” from bullies, asthe witty, heartfelt film earned the brothers rave reviews and a 2003 AcademyAward nomination for best adapted screenplay. He never learned about the Oscarnod, however, as he died in October after a long battle with cancer.

“It was sad because one of my first thoughts was that hewould have been so tickled,” Paul says.

“It felt so surreal,” Chris says, quietly. “He was such apowerful figure that he managed to get inside your head to the extent that youfelt like it was possible that if one person on earth could not die, he wasgoing to be the guy.”

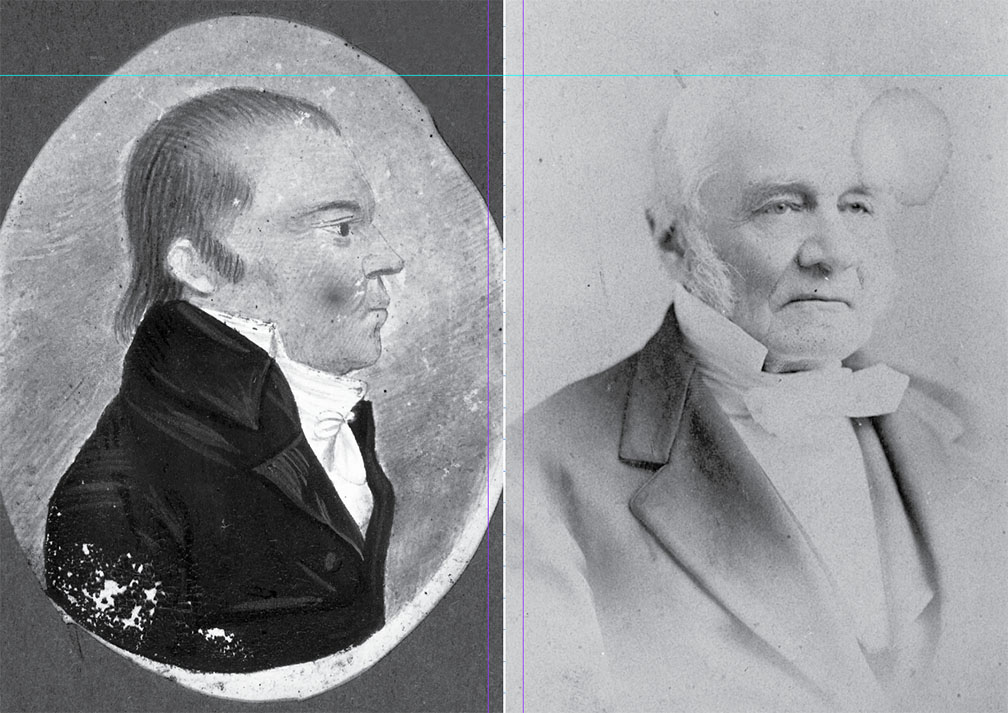

John Weitz, the son of wealthy, assimilated Berlin Jews,fled Hitler to Shanghai and then to New York in the late 1930s, his sons say.By age 19, he was an OSS spy posing as a Nazi officer in that agency’s mostdangerous mission: aiding the German resistance’s plot to kill Hitler. Afterthe war, he helped liberate Dachau, “which forever destroyed a kind ofinnocence for our dad,” Paul says. He subsequently reinvented himself as apioneering designer who starred in his own ads, raced cars professionally, and,in his later years, wrote best-selling novels and non-fiction books aboutHitler’s Germany.

The brothers are the product of his third marriage, toglamorous actress Susan Kohner — daughter of famous Jewish agent Paul Kohnerand Mexican Catholic actress Lupita Tovar. While the Weitz’s Park Avenuehousehold was nonreligious, it was not entirely assimilated: “Our fatheridentified as Jewish almost out of spite toward [anti-Semites],” Chris says.

“He was always scornful of people who changed their names,”Paul says. “The only people he thought should change their names were thefamily members of ex-Nazis.”

The brothers inherited his subversive streak, sometimes tohis chagrin. Dad wanted them to wear twin Navy blazers with insignias; theypreferred shlumpy jeans. When John Weitz hired a German nanny to watch theboys, then 7 and 11, during a vacation, “We tortured her,” Paul says. “We keptasking her what she thought of Hitler until she finally said, ‘He made thecountry work.’ We were like little OSS guys undermining her authority andquestioning her politics until she got so aggravated that she left.”

When Kohner’s famous clients came calling (Ingmar Bergmaneven took them to the circus), the brothers remained cheerfully oblivious.Chris’ recollection of Billy Wilder, now one of the Weitzs’ cinematic heroes:”He didn’t know us from Adam, but he was nice to us because of ourgrandparents.”

By the 1990s, Paul and Chris Weitz, graduates of Wesleyanand Cambridge University, respectively, were determined to launch their ownfilmmaking careers. Their father initially had his own idea of how they shouldproceed: “He kept suggesting that we ring up Merchant Ivory Productions,” Chrissays with a laugh. Instead, the boisterous, bookish brothers snagged scriptdoctoring assignments and persuaded DreamWorks to let them write the 1998animated film, “Antz.”

For their directorial debut, they latched onto Adam Herz’s”American Pie,” which placed them among a growing list of filmmaking brothers(Coens, Farrellys, Wachowskis) whose perspective is not only shared butgenetic. They don’t think it’s surprising that the scions of all that JohnWeitz breeding grew up to make a ribald teen classic: “There is a kind of oldBerlin, knockabout bawdy sense of humor in ‘American Pie,’ which was our dad’s senseof humor, actually,” Chris says.

Nevertheless — in part to counter the raunchy image — theysought to make a more sophisticated, Billy Wilder-ish comedy after “AmericanPie.” They knew they’d found it upon reading “About a Boy”: Hornby’sprotagonist “reminded us of Jack Lemmon’s character in ‘The Apartment,'” Chrissays. “The story is unerringly optimistic, but there’s enough cynicism and acidin it not to make you gag.”

When Hornby and Grant balked at hiring the “pie guys,” thebrothers won them over during a series of social calls (they bonded with Grantwhile getting falling-down drunk in London). They begged Universal for twoyears before landing the project.

Grant, for one, was impressed: “As it turns out, Chris andPaul are probably the most highbrow directors I’ve ever worked with,” he toldNewsweek. “Bizarrely so. They sit around on the set reading Freud andDostoyevsky.”

Since receiving the Oscar nomination, and other “Boy” kudos,the brothers no longer have to beg to direct projects of their choice. They’vetoyed with the idea of filming their father’s story, although they haverejected that idea, for the time being, because “you don’t want tosensationalize it or mess it up,” according to Paul. Instead, they’re workingon another comedy, “The Making of a Chef,” about the escapades of culinaryschool students. Their father would have liked it, they think.

Even though the cooking saga will not feature a pie.

The Academy Awards air March 23 on ABC.