Reuven Rubin’s 1950 painting “First Seder in Jerusalem” at first glance seems like a simple but moving representation of a diverse group of Jews at a Passover table. There are secular-looking kibbutzniks, a Hasidic rabbi, two IDF-uniform wearing soldiers, immigrants from Africa, and a young Haredi boy with sidelocks. But at second glance, one notices what makes the assembled group really diverse. Seated to the left, with his palms turned upwards, is, yes, Jesus.

Rubin, né Zelicovici, was born in Romania in 1893, and would later serve as the nascent Jewish state’s first ambassador there. As a child, he demonstrated a precocious artistic ability and at age eighteen the local Zionist leader Dr. Adolf Stander sponsored his studies at the Bezalel school of art in Jerusalem. But, upset at being assigned to an ivory carving workshop, Rubin dropped out and continued his artistic studies in France before returning to Romania. In 1923, he returned to Mandatory Palestine where, five years later, returning from one of his art shows in New York, he met his wife Esther, a young woman from the Bronx who had won a free trip to Palestine in a Young Judea competition.

Two years after Israel’s founding, Rubin painted “First Seder in Jerusalem,” inspired by the hope and potential of the developing Promised Land. It is steeped in symbolism. Jerusalem’s Old City walls can be seen through the windows. The white-haired figure embracing his son on the right is the artist himself. Behind him stands Esther, pouring some wine. And as even lay art historians might notice, the figures are positioned to mirror Leonardo da Vinci’s “The Last Supper.” That famous image depicts Jesus with his disciples, the evening before his execution by the Romans.

As Tsvi Sadan writes in “Flesh of Our Flesh: Jesus of Nazareth in Zionist Thought,” the revival of the modern Jewish state negated nearly two millennia of Christian thinking that the Jews had been supplanted on the stage of history. Rubin is therefore purposely playing off of the most famous rendering of Jesus’s Paschal meal. As the art historian Gabriel Goldstein has suggested, “the inclusion of the resurrected Jesus is to remind the world that the Jewish people also suffered and died but yet rose again to life in their own land. Rubin’s title stands in contrast to da Vinci’s – this is a first Seder not a last supper.”

The dreamlike aura in the image is no accident. “The peaceful scene,” Goldstein continues, “is just a dream of a peaceful future that has not yet arrived,” an impression strengthened by Rubin’s rendering of himself resting on his hand, staring as if unaware of the others at the table, lost in thought.

Rubin’s painting emerged from the modern-day exodus of Jews from across the globe to build the new state and their stunning defeat of surrounding Arab armies, the Pharaonic forces of their day. As the Rubin Museum curator Carmela Rubin has noted, “the exceptional new reality demanded a didactic mode of expression, one that would elevate his narrative beyond the reality of mundane existence.”

Alas, the full realization of Reuven Rubin’s dream has not yet materialized. Social fissures in Israel and antisemitism worldwide have pushed off the peace of mind, and of Jerusalem, that Rubin hoped for. But the chords of Jewish unity remain strong despite challenges. And Christian Zionists are among the leading supporters of Israel in its fight against those who seek its destruction, with millions offering not supersessionism but support for their Jewish friends.

Rubin’s image, then, is perhaps the perfect painting for our moment, a reminder of how close we are to meriting that era of ultimate redemption the Haggadah hopes for – perhaps even next year, in Jerusalem.

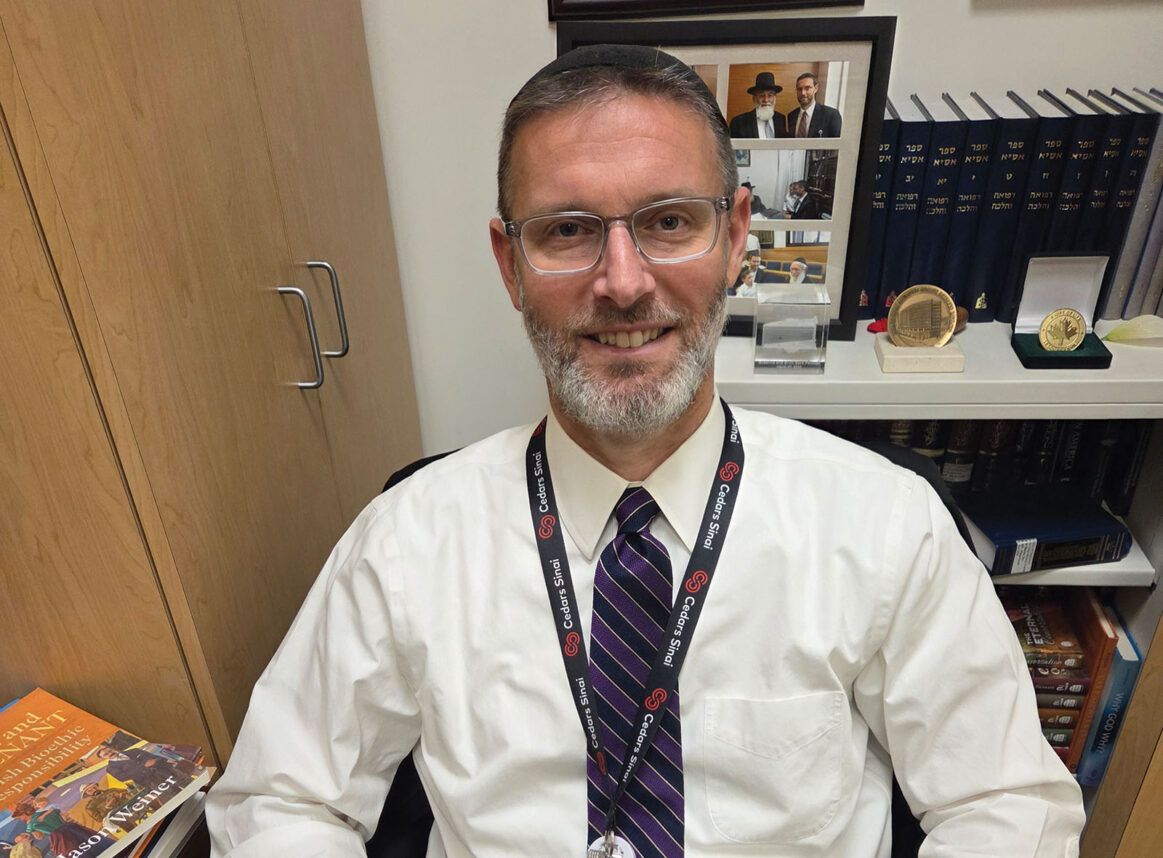

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include “The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada,” which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, “Esther in America,” “Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth” and “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.”