If there’s one theme that’s come to dominate the rhetoric of the past few years it’s the notion of the binary, that way of looking at the world through a prism of only two possibilities. Nowhere is this impulse more pronounced than in questions of identity. It’s a lens through which one’s ethnic, racial, or national identity places them in the rigid categories of oppressed or oppressor, and it follows that these two categories are respectively good and evil. There is no middle ground, no dialogue, no murky gray zone—no uncomfortable space.

It’s an anti-intellectual sleight of hand, the trickery of which eludes even some of the most careful thinkers—because, after all, our world is not an easy world these days, and it’s much simpler to consider only two options and be done with it. We have traded complexity and nuance for something less philosophically cumbersome.

The trouble with this thinking is that everything in our world defies its illogic. People are no longer just one thing, if they ever were to begin with. For one, the migration and movement of people along with the fluidity of national borders make it impossible, even nonsensical, to assign immovable meaning to one facet of a person’s identity.

A new art exhibition at the Jewish Museum in the old ghetto of Venice, Italy, urgently reminds us that there is forgotten value in the nuances of identity, and brings to the forefront the possibility for “stories and cultures to meet and exchange.” In conjunction with Opera Laboratori and Shifting Vision, the exhibition, “The Contours of Otherness,” which opened April 21 and runs in conjunction with the Venice Biennale (through October 27), is curated by Jemma Elliott-Israelson who works with Shifting Vision. It’s the first exhibition for which Elliott-Israelson is lead curator, and for her, the idea of identity and migration, and how one’s “identity dissolves or resolves over time when you migrate” was key in coming up with the premise of the show.

“Migration can be many things,” Elliott-Israelson told me in a conversation I had with her and two of the artists whose work is featured in the show: Amit Berman and Elisheva Reva. Elliott-Israelson is both Israeli and Canadian, and has lived freely in many places around the world though she now resides primarily in Italy. But migration isn’t always voluntary. Sometimes we’re forced to migrate because of famine and poverty, or political or social issues. There are “many different reasons why we move,” she says, “but the fact is that everybody does move now, so how do we reconcile issues related to our identity,” whether social, cultural or religious? And what does it mean to explore the otherness of ourselves in addition to those around us?

There could hardly be a better space to respond to these questions than in the old Jewish ghetto of Venice.

For Elliott-Israelson, the ghetto is a “kind of encasement for holding that kind of identity, that otherness.” And certainly Jews are no strangers to the sensation of being different, and to the nuances of identity that come along with that. Jewishness is an identity that’s always in flux, in movement. Throughout history, Jewish identity both remains the same and changes wherever it is found. American Jews, for example, are different from European Jews, and Jews from Morocco or Ethiopia are different from South American or South African Jews. And yet we all read from the same Torah and eat the same bread on Shabbat. Iranian Jews may put scallions at their Seder table and Jews from Yemen may not use a Seder plate at all, but every Jew says “Next year in Jerusalem” at the end of the Passover Seder: difference conjoined with sameness.

“You take the essence of yourself wherever you go,” says Elliott-Israelson, and “that can be preserved in certain instances and also attacked … and maybe you accept this changing of yourself through language and customs or culture.” Perhaps this is why Jewish identity can be hard for outsiders to grasp: It is constantly moving and shifting, even as it stays the same. Though Jews are adept at assimilating into other cultures, we seem to always keep a large part of our cultural and religious identity with us.

Perhaps this is why Jewish identity can be hard for outsiders to grasp: It is constantly moving and shifting, even as it stays the same.

The Venetian Ghetto, established in 1516 when it was decreed that Jews must be segregated from the rest of the population, was Italy’s (and Europe’s) first ghetto. It’s a place where the history of people “othering” Jews is old and dark. And nearly 500 years later in the 21st century, it stands not only as a reminder of how ancient is the othering of Jews, but also as a touchstone to today’s growing antisemitism. The ghetto embodies both past and future. But the present, as this exhibition shows, is full of possibility and hope. There’s “a lot of youth in the show,” says Elliott-Israelson, “and it’s a great juxtaposition.”

The show features the work of ten artists including Jonathan Prince, Amit Berman, Elisheva Reva, Flora Temnouche, Danny Avidan, Lucas and Tyra Morten, Lihi Turjeman, Deborah Werblud, Laure Prouvost, and Yael Toren. All works address the themes of migration, identity and cultural memory, and despite the fact that many reference Jewish identity in some way, the show has a deeply universal appeal and also reflects the broader theme of the Biennale, which is “Strangers Everywhere” (“Stranieri Ovunque”).

As Elliott-Israelson points out, migration and ghettoization often go hand in hand. The shape of otherness is sometimes molded by those who migrate. From Toronto to San Francisco to London to Los Angeles, every major city has communities that have recognized their difference and chosen to segregate themselves into ethnic neighborhoods. “It’s not always a bad thing,” said Elliott-Israelson. “It’s not that they don’t engage with the larger world, but there is an aspect of wanting to preserve their cultural identity through living in the same area.”

Sometimes it’s about survival. When you migrate to a foreign country you adapt quicker when you have a community of people who speak your language and who can help navigate bureaucracies. It’s also about community. Being close to those who share your traditions and foods and way of seeing the world makes it easier to navigate otherness. In Los Angeles, for example, you’ll find Chinatown, Little Armenia, Little Ethiopia, Koreatown and Croatia Place among many others. These are enclaves of both otherness and belonging. And don’t forget the Pico-Robertson and Fairfax-Hancock Park communities, populated by large clusters of Jews, mostly Orthodox (another layer of identity).

Jewish identity, especially for those Jews who take it seriously, is about being the perpetual other, about being both at home and not at home wherever we are. It’s about being separated, literally and metaphorically, even when we have successfully integrated into another culture or country. There’s a kind of movement inherent in the relationship between the Jew and the place where he or she lives. It’s a constant negotiation, a tension and a pulling back and forth.

Jewish identity, especially for those Jews who take it seriously, is about being the perpetual other, about being both at home and not at home wherever we are.

One of the dark ironies of Jewish history is that Jewish identity is often imposed on those Jews who crave its erasure. We’re seeing that phenomenon at work today with the surge in antisemitism. Those who hate Jews don’t discriminate between Jews who take their identities seriously and those who don’t.

Historically, Jews often enact a kind of “self ghettoization … it’s not a religion that wants people to convert to it,” she says. “It’s not inclusive by nature, and we have to know that about ourselves. It’s part of the religion and culture,” and the show plays with its identity and borders and contours.

With “The Contours of Otherness,” Elliott-Israelson wants us to reflect on “when otherness is imposed and when we take it on ourselves to feel different.” Sometimes “we don’t want to be accepted and sometimes we do but it’s complicated, so I wanted this show to be something artists could approach through their work from that lens and not necessarily have to speak to the Jewish aspect of it, though some did in a meaningful way … but that’s also Jewish identity.” Elliott-Israelson sees the show as “holding space for all of those things.”

The question of whether all art is political is one that will never be fully resolved. The tendency to immediately associate a set of political beliefs with where a person, especially an artist, comes from is especially pronounced right now, especially when it comes to Israel. But for Elisheva Revah, who lives and works between Tel Aviv and Paris and was raised in the Judah Mountains of Israel, it’s not just about where you were born; it’s about all the complex strands of identity that are woven together.

“I’m not only Jewish,” she says, “my father is Moroccan, my mom is German, very German, and those two cultures have so much beauty and wisdom in them. I was born in Israel, my parents were artists, hippies, and they became religious so I went through Orthodox school and I was nourished from so many different cultures and I have so many roots.” All of these roots are part of her everyday life and creative work. “I gain a lot of power and strength from connecting to my roots,” she says.

The exhibition features Revah’s “Challah,” a performance in which she recreates the feminine act of weaving bread for Shabbat. Revah was trained as a professional dancer, and while much of her work involves the body, the focus is primarily on the mystery of femininity and womanhood as a particular form of otherness. For Revah, there’s a mystery to femininity, and that’s not a bad thing because, as she says, not everything needs to be known.

The performance plays on a screen during the exhibition, but I was able to watch it live in the garden of the ghetto’s Spanish synagogue. Revah brings new life into the space with this performance in which we see four women, dressed in white with long braided hair, kneading a giant mound of dough for challah, sometimes even using their bodies to push and pull against it, molding and forming it with urgency and intensity. As they finally braid the challah, we realize that the mundane has been the sacred all along. The feminine act is a spiritual one. There is a sense of mystery and longing as we watch the women move their bodies as if in a dance while they continue to braid. The performance is a prayer of sorts. The act of making challah is, on the surface, simple. But Revah reveals the spirituality of this ritual.

Shabbat is one thing that sets Jews apart from the world, but while Revah’s work performs this otherness, it simultaneously insists that we, “all have the same rituals that are happening in slightly different ways.” “Challah” is “about femininity, it’s about nourishment, it’s about the mystery of the woman … and that can relate to any woman, and even men.” It’s about bringing something “that has an essence that anyone can relate to,” through the lens of her own culture. “Because I come from a blend of very different cultures, I see that all cultures are the same.”

Watching the performance of “Challah” is truly a special experience. But the artist’s reflections on the performance add an important layer of understanding. In our conversation, Revah recounted the days leading up to the performance at the show’s opening as she considered what she had chosen to perform. It’s a quiet performance. Rather than listening to sounds, we listen to the absence of sound as we watch the women work. Before, she said, “I had done performances that were very powerful, like birth. I would shout and give birth to something, something that is more dramatic and expressive. And I panicked because I said, ‘I’m going to Venice, to the Jewish museum, and I’m working on dough? This is what I’m going to do? I’m going to just sit there and work with the dough? And I had moments of panic, but then the answer came to me and I realized that, yes, especially now the only thing I have to do is to bring something that is a symbol of what I have to bring to the world. I don’t have to shout.”

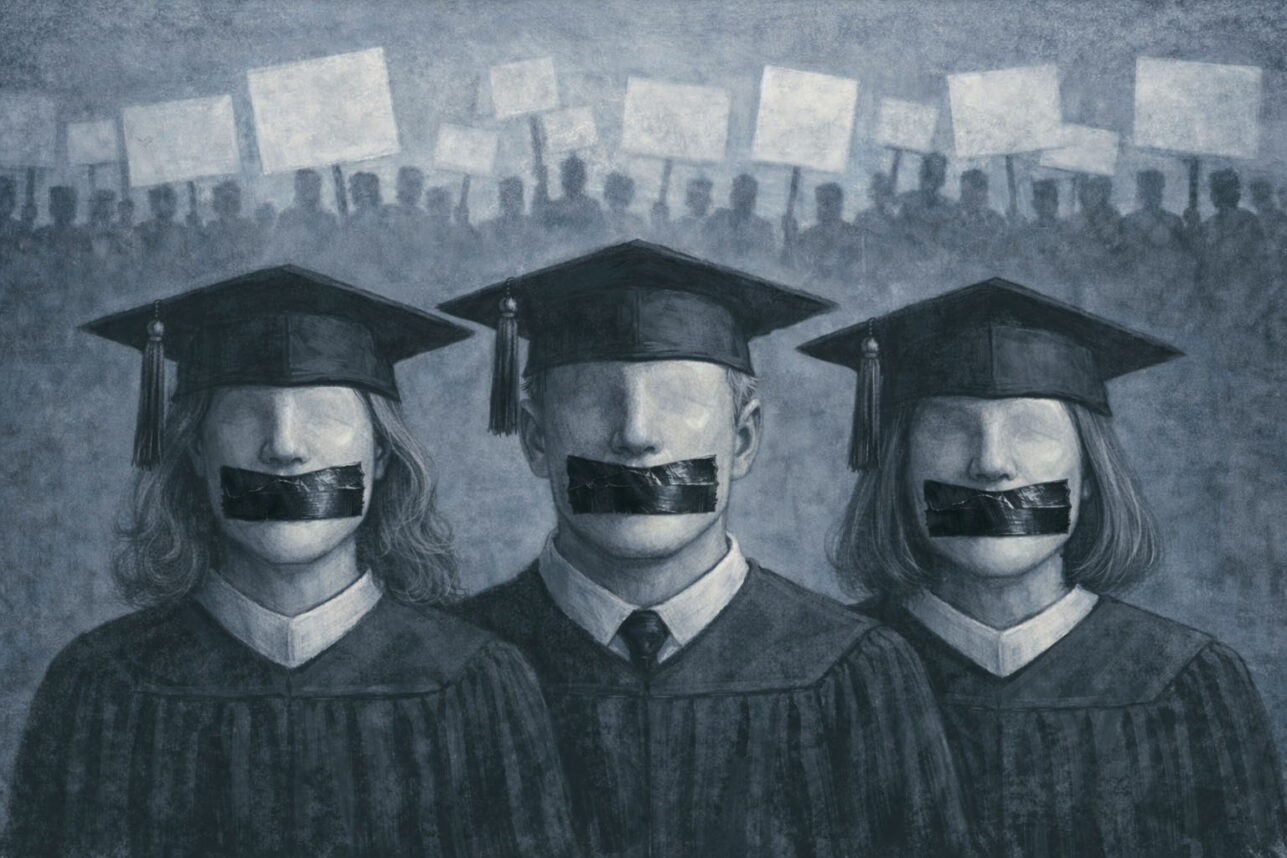

There is a lot of shouting today: on campuses, on social media, all around the world. The noise is deafening. “There is much less power in shouting,” says Revah. But “I see a lot of potential in women’s energy. It’s not out there. It’s not loud. And especially today, with what is going on in the world, I feel there is so much need for this inner process and there is so much power in the quiet.” But it’s not just about being quiet; it’s also about mystery.

There is a lot of shouting today: on campuses, on social media, all around the world. The noise is deafening.

“I think we are lacking mystery today,” says Revah. Considering the social media obsession with airing everything from the latest meal eaten to the most offensive grievances, I can’t help but agree. “Not everyone needs to know everything all the time,” says Revah. “The symbol for the woman is the moon, which is not out there all the time. It must be revealed, and it comes and it goes and it’s the light that keeps shining in the dark.”

Identity doesn’t need to be screamed to be real.

Art can whisper its agenda without having to be political. It can be about healing the world, about connecting to one’s history, memory, and tradition and then drawing on those things to create rather than destroy. The process of creating is also about drawing from the past, from everything that is already present. It’s about reflecting on who we are and where we have been, and bringing those insights to the world in a new way. Revah does this in a way that is magical.

Throughout history, despite endless persecution and discrimination, Jews have insisted on creating rather than complaining. Consider Hollywood: In the early-twentieth century, men like Louis B. Mayer, the Warner brothers, Adolph Zucker and Carl Laemmle who were first- and second-generation Jewish immigrants were drawn to the film industry because it was one of the only avenues open to them given the rampant antisemitism in the U.S. With the advent of World War II and the Holocaust, things only got worse for Jews. But these creators, artists and visionaries kept putting art and entertainment into the world. In a post-Oct. 7 world, with echoes of past tragedies loud than ever, the artists of “The Contours of Otherness” are doing the same thing.

I hope that “when people meet me,” says Elliott-Israelson, “they meet an Israeli that they see is open and kind and cares for humanity and I don’t have to be labeled as any one thing. But through my work I’m doing something good and it’s enough, it’s enough. I’m contributing something positive to the world as an Israeli: the quietness and just doing your own work. But it’s a difficult moment because there’s a lot of noise and it can feel like you’re being constantly misunderstood and misrepresented, being spoken for by people who don’t know anything about the situation.”

Art can of course be political, it can be about healing, it can be about beauty for the sake of beauty; but it can also educate. It can draw us into a space of dialogue even with images of everyday things. Amit Berman, a painter and photographer based between Tel Aviv and Italy, is a master at this. He typically begins with photography, and these photographs become inspiration for his paintings. His piece for the show is called “A Transferable Safe Space.” The title is evocative of a history in which Jews have often had to migrate, to bring with them their places of safety and recreate them wherever they find themselves.

But part of the beauty of Berman’s piece is its universality. There’s nothing definitively Jewish about the painting, at least not on the surface. A white shirt that happens to be the shirt Berman paints in every day hangs, empty, against a wall. I see “a body in the empty shirt,” writes Elliott-Israelson, “either a shell of a former self or a self that’s waiting to be inhabited with something new.” Or perhaps it’s both.

We know that we are looking at an artist’s space because there are brushes and paint visible—not placed carefully away, but in use. We see both stillness and motion, a visual metaphor of “the tension between the need to preserve one’s roots and the need to adapt to a new context.” The title answers the question of what kind of space we are looking at: It’s one that is safe, and it’s one that travels with the artist.

At first, the idea of a safe space being transferable feels antithetical to the idea of feeling safe. But Berman’s painting depicts an unstable moment in his life when he found stability in creating. “The whole idea of safe spaces for me is about my rituals, my habits, my passions and the ability to preserve it,” says Berman, who grew up in Israel, but as a child traveled extensively. As an adult, he became a flight attendant for three years. For him, moving around the world was familiar, and whenever he stopped in a city during a layover, he wanted to be alone and to look at things, “to feel the place.” He would establish rituals that kept him safe wherever he went. “I felt very stable everywhere, I felt like it was my home.” Having been based much of the time in Italy, he has a strong connection to the country and to the people. Berman remembers being in Milan during the beginning of the COVID pandemic, and “it was very dramatic and very hectic and it was the beginning of it in the western world, and I made a decision to stay by myself there.” At the time he was working for Israeli Ministry of Foreign affairs, in security, and he decided to stay even though everyone was told to go. “I decided to stay because I felt safe in my space and what you see in the painting is my apartment in Milan when it started to become my home studio and when I found serenity and harmony and sense of stability and safety in that space.”

“The whole idea of safe spaces for me is about my rituals, my habits, my passions and the ability to preserve it,” says Berman.

But if there’s harmony and stability in this piece, there’s also a sense of tension. Berman resumed working on this piece—he’ll often start something and return to it much later—around the time he had to change his studio in Tel Aviv, and the finished product is a reflection of the tension between two different moments—one of change and one of stability. “For me, it’s very important to have this sense of movement in every work I do, in every painting I want to preserve this sense of movement,” says Berman. It can be “physical movement, if you can see a body, or if you can feel that the space has just been visited or left behind or the sense of anticipation, the sense that something is arising.”

I spent some time looking at Berman’s other work, and was especially struck by the titles of his pieces, which are often in contrast to what we see in the image. A title can keep us in or out of a work of art. But Berman’s invite us in and guides us in how to see his work. They ask us to see his work in a way we otherwise might not have. They invite us into a conversation.

One painting, “By the rocks of doubt,” depicts two men embracing against the sharp lines of the sky, sea and sand. There is a disconnect between what we see and what the title asks us to see. We’re asked to look beyond the image in which a feeling of doubt is not readily apparent. Likewise, in “sometimes I feel sadness for no apparent reason,” bright and vibrant flowers stand against a bright blue background. There’s nothing inherently sad about the image, but it is something to which many people can relate. “Sometimes,” says Elliott-Israelson of Berman’s drawing, “I’ll be in the most beautiful place and a wave of anxiety or dread or sadness comes over me, and I think this is a very real and very universal thing.”

“I don’t want to feed the meaning to the viewer or tell them what it’s about,” says Berman, “I want to have this dialogue.”

As I perused Berman’s work I played a game with myself in which I would look at the painting before the title and decide what it was about. Then I would return to the title, and every time I was surprised because there was a disruption of what I thought I was seeing. But that’s where real dialogue comes in—it disrupts and compels us to think and question and grapple with meaning and truth.

I asked the artists and curator what they would like people to carry away with them after the show. “I want them to take the fact that we are, even with this beautiful otherness, even with different identities and origins … all human and very much similar,” says Berman. “For me, half of my life is in Italy and my friends there aren’t Jewish but Italian and Christian. I felt a sense of isolation in the beginning, but it’s important to have this interaction, to show the similarity. It’s about building the safe space.” As an Israeli, he wants to build a bridge for people “who may feel intimidated by contacting us or being by our side because being by our side doesn’t mean to support any ideology or political statement. It’s just being human and being a friend … that’s the kind of interaction I’m looking for.”

“When I create my performance in the video art,” says Revah, “I’m searching for other women to participate. Everywhere, even in Venice I was looking for women, and they were ready to take part. None of my Venice performers were Jewish. There was a Korean girl, a Ukrainian girl, one Italian who lives in Paris, and one Italian from Venice but they were all feeling very connected to my work and were willing to take part. I believe that even if I’m using my own roots and my own world to create something, the essence is femininity and every woman can relate … I want people to feel that power of the feminine.”

“The point of the show,” says Elliott-Israelson, “is that not everything is so binary. That’s the whole point. These concepts are not binary, your identity is not binary, most people are not from one place. I could feel more Israeli on one day and much more Canadian on another day and it’s all fine. That’s really what we are trying to communicate with the show in many ways.”

“The point of the show,” says Elliott-Israelson, “is that not everything is so binary. That’s the whole point.

It’s a complicated time to put together a show like this; perhaps it’s also the moment where it’s most necessary. “I know people will view this show through the prism of October 7,” says Elliott-Israelson, “but, and this is personal to me, I’m not making constant explanations for what’s happening in a war where I don’t have control over anything. I do want to be positive about being Jewish, about being Israeli. I think Israel is a beautiful country with beautiful people and it has very hard parts, but I want to spread my joy. This is who I am and these are the artists who I know and these are the beautiful things that they are creating and there’s a pure positivity about this that has nothing to do with politics. And I’m just trying to make a difference in my own corner by saying I am a young, international Jewish Israeli curator and these are the things I’m trying to create. And I hope that people can enjoy them just through that, through the prism that is coming from a really good place. I tried really hard to make this show as non-political as possible … I tried to make it something that anybody could come to and see some of these works and feel something.”

Monica Osborne is a former professor of literature, critical theory, and Jewish studies. She is Editor at Large at The Jewish Journal and is author of “The Midrashic Impulse.” X @DrMonicaOsborne