bilhagolan/Getty Images

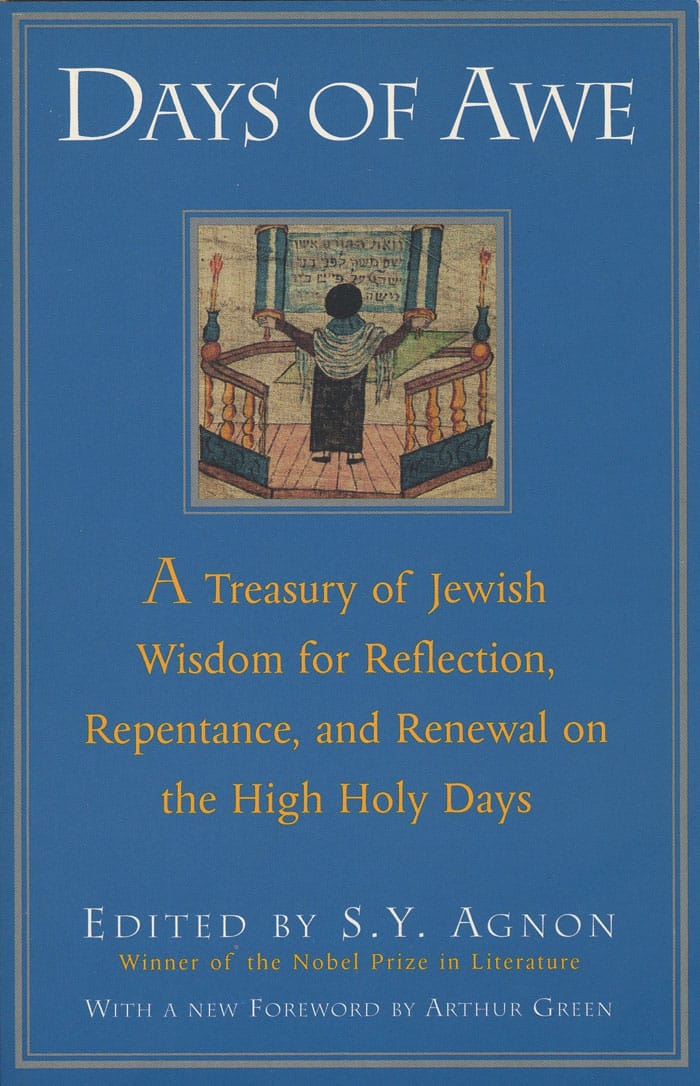

bilhagolan/Getty Images It was a Rosh Hashanah like no other. It was the Rosh Hashanah when I felt as if I held a “Book of Life” in my hands. On that day, for the very first time, I opened S.Y. Agnon’s beautiful High Holy Days book “Yamim Noraim — Days of Awe.”

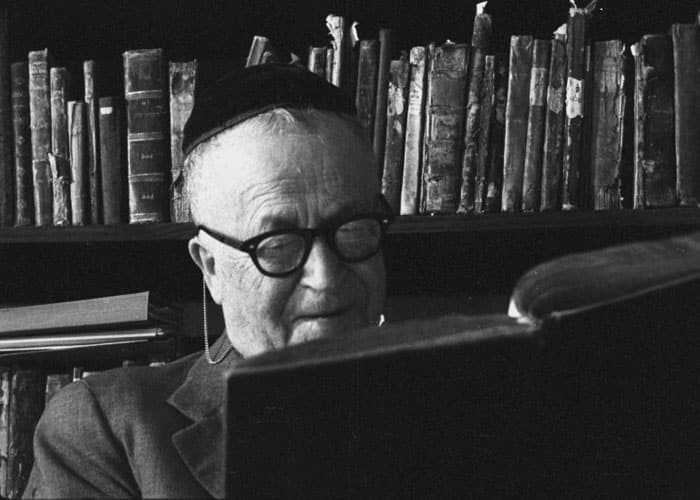

Eighteen years ago, just one week prior to that same Rosh Hashanah, I started my journey into the literary world of Nobel laureate S.Y. Agnon. I had just turned forty, a birthday traditionally marked as the age when one may start studying Kabbalah. I opted for Agnon’s books instead. After reading a few short stories, I called Professor Arnold Band, my beloved teacher from UCLA and one of the world’s foremost scholars in Agnon’s writings.

“I want to start reading Agnon. Where should I begin?” I asked Professor Band.

“I want to start reading Agnon. Where should I begin?” I asked Professor Band.

“Next week is Rosh Hashanah” he replied, “so start by bringing Agnon’s book ‘Yamim Noraim’ (‘Days of Awe’) with you to shul. Keep it by your side throughout services. It’s what Agnon would want you to do.”

I followed Professor Band’s advice, and having Agnon’s “Days of Awe” by my side elevated my Rosh Hashanah experience to another level.

The first time I opened “Days of Awe” that day, I felt as if I entered a room where a fascinating array of classical Jewish sources were having a lively conversation about Rosh Hashanah.

The first time I opened “Days of Awe” that day, I felt as if I entered a room where a fascinating array of classical Jewish sources were having a lively conversation about Rosh Hashanah. Talmudic rabbis, medieval Kabbalists, Sephardic philosophers, Hasidic rebbes and Halakhic scholars all seemed to be sitting around the same table. They came from different places and lived at different times, but the creative manner in which Agnon arranged them brought them to life in an interactive dialogue that transcended time and geography. Words that were originally spoken hundreds of years apart poetically flowed into one another. They shared ideas about Rosh Hashanah’s unique customs, its prayers, the power of repentance, the sounds of the shofar and the symbolism of the Book of Life. When reading their words, I was transported into their world. I could hear their voices. It was as if Agnon had invited me into a timeless and ongoing Beit Midrash about the High Holy Days.

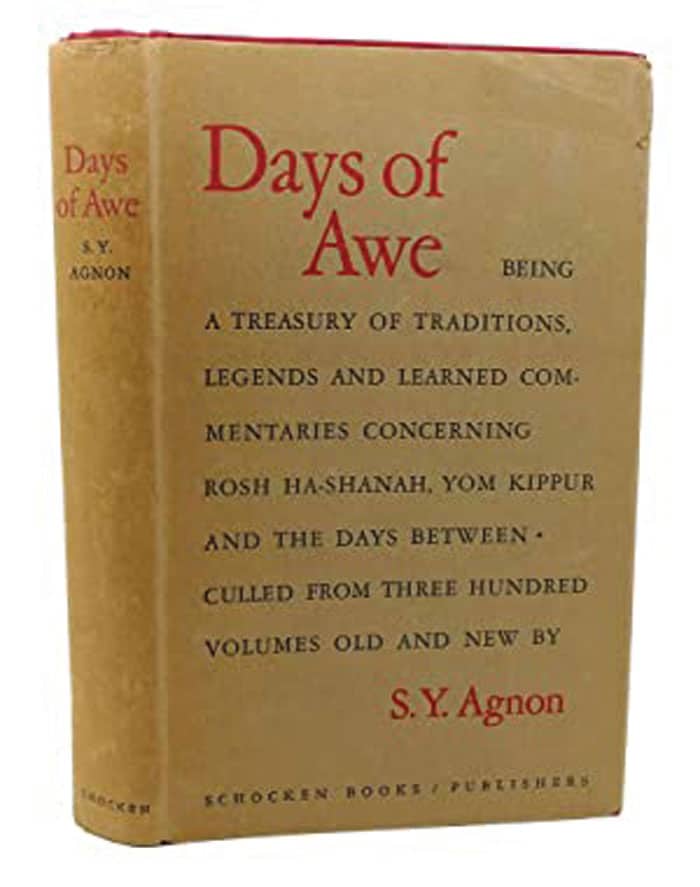

Many refer to “Days of Awe” as an anthology edited by Agnon, but I don’t think that paints an accurate picture. It’s much more than just an anthology. In “Days of Awe,” Agnon’s artistic talent is not expressed in conceiving a plot or inventing imagined characters. Using his masterful storytelling skills, Agnon composed “Days of Awe” by creatively arranging a treasure trove of Jewish sources about the High Holy Days, letting them tell us the epic story of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

Many refer to “Days of Awe” as an anthology edited by Agnon, but I don’t think that paints an accurate picture. It’s much more than just an anthology. In “Days of Awe,” Agnon’s artistic talent is not expressed in conceiving a plot or inventing imagined characters. Using his masterful storytelling skills, Agnon composed “Days of Awe” by creatively arranging a treasure trove of Jewish sources about the High Holy Days, letting them tell us the epic story of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur.

One of the first reviews of “Days of Awe” was written like a letter to Agnon, praising him for fostering Jewish unity through his book: “All of the sources in this book are like good neighbors to one another, one united family. You successfully bound them within one book and breathed life into all of them as one unified soul.”

“Days of Awe” is not Sephardi or Ashkenazi, Hasidic or Mitnagdic, Halakhic or philosophical. It’s all of those voices together, and many more, joined in harmony by Agnon’s literary magic.

Indeed, “Days of Awe” is not Sephardi or Ashkenazi, Hasidic or Mitnagdic, Halakhic or philosophical. It’s all of those voices together, and many more, joined in harmony by Agnon’s literary magic. On Rosh Hashanah we pray to become “Agudah Achat”—one unified body. In “Days of Awe,” Agnon fulfilled that prayer for us, even if only in a book.

On my first Rosh Hashanah with “Days of Awe,” its deepest impact came during my most physically and emotionally challenging moment of the day: the blowing of the shofar. It’s always a lonely experience blowing the shofar. You’re all alone and on your own, with everyone else just listening. I usually spend the moments beforehand meditating on fulfilling the mitzvah properly, and doing breathing exercises.

But that year, I spent those moments reading Agnon’s selections about the shofar. My entire experience was transformed. I scratched my pre-shofar remarks and instead shared with the congregation the beautiful passages in “Days of Awe,” where Agnon’s “characters” discuss both the story and deeper purpose of the shofar blasts.

The Sephardic Rabbi David Abudraham links the shofar to Rosh Hashanah as the anniversary of creation, and the blasts resemble a royal ceremony when we celebrate God’s sovereignty over the universe.

The Talmudic Rabbi Abahu takes us back to the first-ever shofar blowing, when Abraham blew the ram’s horn in place of sacrificing his son.

The Hasidic Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berdichev speaks passionately about the shofar blasts as a reenactment of the shofar the Jewish people heard upon receiving God’s Torah at Mount Sinai.

In storytelling worthy of Agnon’s Nobel Prize, these three rabbis told me that the shofar’s different notes tell us various stories.

“Days of Awe” also taught me that the shofar is endowed with a deeper meaning and message.

For Maimonides, the shofar blasts awaken our souls and stir us toward improving our actions.

Ancient philosopher Philo of Alexandria contrasts musical horns as instruments of war vs. the shofar as an instrument of peace.

Chabad Hasidism founder Rav Shneur Zalman of Liadi emphasizes that the shape of the shofar must be bent, as it resembles a person bent in prayer before God.

When I blew the shofar that day, the long regal blasts (Tekiah) took us back to the six days of creation, the broken notes (Shevarim) appropriately sent us to the Akedah, and the staccato notes (Truah) transported us to the trembling aura of Mount Sinai. As we journeyed through these epic moments, I also felt the blasts pierce our souls in the Maimonidean sense, and inspired by Philo and Rav Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the shofar became our vehicle of prayer for world peace.

Among many other things, Agnon’s book is a soulful tribute to the wonders of Jewish diversity.

“Days of Awe” magically turned my shofar into a musical storytelling instrument, where multiple Jewish voices harmoniously opened our hearts to an uplifting shofar experience. Among many other things, Agnon’s book is a soulful tribute to the wonders of Jewish diversity.

What motivated Agnon to create this book, and who was its intended audience? Why did Professor Band tell me that having “Days of Awe” by my side on Rosh Hashanah is what Agnon would want me to do?

Agnon tells a poetic story from his childhood, when at the tender age of four, his father and grandfather walked him to what may have been his first-ever High Holiday service. “The heavens radiated a sense of purity, quiet filled the earth, and all of the streets were clean,” Agnon lovingly recounts.

Dressed in his special holiday clothes, the curious young Agnon approached what he calls the “House of Prayer” (Beit Ha-Tefillah). He looked through the window and was astonished by the sight of everyone dressed in white, wrapped in prayer shawls adorned with silver crowns. A warm light radiated throughout the room, and the young boy who “was not yet able to contemplate deep ideas” nonetheless felt that this House of Prayer permeated an aura of sacred beauty.

The sight of worshippers engaged in heartfelt prayer, along with the sweet sounds of their voices chanting liturgical poems, mesmerized the young lad. Nothing else in the world mattered: “It seemed as if the ground I walked upon and the streets I passed through, and indeed the world in its entirety, were nothing but a corridor leading me to this house.”

The young Agnon loved everyone and everything he saw in the House of Prayer, and hoped this magical scene would never come to an end.

But alas, it did come to an end. Something suddenly changed in the House of Prayer, and the young lad was saddened by what he saw. “My soul suddenly felt wrinkled,” he recounts, “and I burst out crying.”

What happened that caused him to cry?

“The congregants shattered their pleasant appearance,” recalls Agnon, “as well as the appearance of the House of Prayer and of the day itself.”

The sweet sounds of prayers and chanting abruptly gave way to the noise of idle chatter. The same people who were praying so beautifully took a break and began chatting. What Agnon had called the “House of Prayer” (Beit Ha-Tefillah) suddenly became the less spiritual “House of Gathering” (Beit Ha-Knesset).

“My heart was heavy over this, and I burst out into tears.”

This experience was embedded in Agnon’s heart for many years. Growing up, he witnessed this scene again and again, and the same feelings overtook him.

As a learned Jew with a deep sense of piety, Agnon was determined to come up with a creative solution that would inspire a deeper, more meaningful and more fulfilling experience for Jews on the High Holy Days. The wholeness he wanted for every Jew mirrors the search for wholeness in his own invented characters.

“I wondered,” asked Agnon, “is there nothing other than the prayers and liturgical poems through which the Jewish people can connect to God on the High Holidays?”

“I wondered,” asked Agnon, “is there nothing other than the prayers and liturgical poems through which the Jewish people can connect to God on the High Holy Days?”

In other words, can those moments when the prayer services seem long or when we close the Machzor and step out into the lobby for a breather also be endowed with meaning?

Year after year, Agnon prepared for the High Holy Days by looking through various books from the Jewish tradition, pulling out the gems as pieces to study on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. It dawned on him that these gems of wisdom would make a great book that could help address the phenomenon that brought him to tears when he was four.

He put pen to paper, and after two-and-a-half years of labor, Agnon gave birth to “Days of Awe.” He called it “a new book filled with ancient wisdom,” and said “it’s a book to be read [in synagogue] in-between prayers.” As Professor Band told me, Agnon wants us to take this book to shul. The Machzor helps facilitate a spiritual talk with God, while “Days of Awe” helps stimulate a meaningful conversation with our fellow congregants.

The circumstances under which Agnon created “Days of Awe” infuses it with deeper meaning. He first started working on it in 1935, two years after Hitler came to power.

“I wrote this book during troubled years” said Agnon, “when our violent enemies stood up to destroy us.”

This was painful for Agnon, for while he now made his home in Jerusalem, he was born and raised in Europe. In many ways, his heart was still in his birthplace of Buczacz, where he first experienced High Holy Day prayers with his father and grandfather.

As the winds of war raged in Europe, violent Arab riots plagued the streets of Jerusalem, including in the Talpiot neighborhood where Agnon lived.

“While working on this book, there were many times at night when I was forced to turn off my lamp and lay down on the floor, so as to avoid stray bullets that flew by my house” recalls Agnon. “Thankfully, God granted me life so that I can do my work and complete my labor.”

The troubled circumstances in Europe and Jerusalem were “Yamim Noraim” for the Jewish people. In modern Hebrew, the word “nora” also means awful, and typical of the multiple meanings in Agnon’s story titles, Agnon may have had these awful events in mind when naming this book “Yamim Noraim.” More than just a collection of sources, “Days of Awe” is an offering from the depths, mi’ma’amakim, of Agnon’s soul.

“Thank God, many Jews around the world now read my book on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur” wrote Agnon.

As a writer, he was a Nobel laureate, but as a Jew on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, S.Y. Agnon remained that four-year-old boy who gazed with astonishment into the House of Prayer.

In his Nobel Prize address, Agnon mentioned only three of his own books by name. One of them was “Days of Awe,” because the High Holy Days held a special place in his heart. As a writer, he was a Nobel laureate, but as a Jew on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, S.Y. Agnon remained that four-year-old boy who gazed with astonishment into the House of Prayer.

Shanah Tovah.

Rabbi Daniel Bouskila is the director of the Sephardic Educational Center and the rabbi of the Westwood Village Synagogue. In the spirit of Agnon’s “Days of Awe,” he proudly works with both Sephardic and Ashkenazic communities.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.