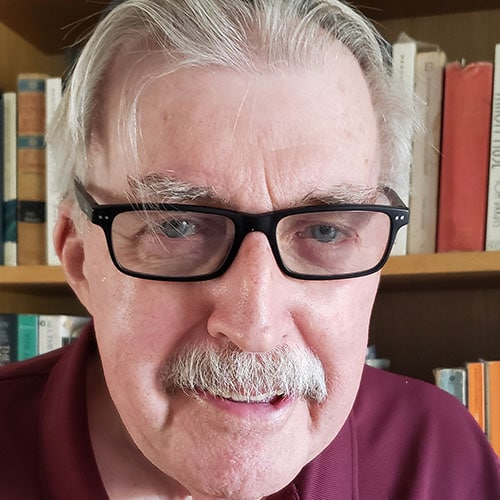

Although he celebrated his 80th birthday two months ago, Rabbi Elliot Dorff has a schedule that would wear out someone a quarter of his age. The author of 29 books covering a wide range of interests, including bioethics, epistemology, and the depth and breadth of Jewish law, Dorff teaches at UCLA School of Law and American Jewish University (where he is the Sol & Anne Dorff Distinguished Professor in Philosophy) and is involved in a multitude of local and national organizations.

But when asked what had the biggest influence in his life, the answer is surprising: “Camp Ramah has had a really important impact on my life.”

Sitting in his sun-filled home, Dorff explained that “in the beginning – I started when I was 12 years old in 1955 – it was simply because it was just joyous. It showed. We sang a lot together, we danced together, we put on plays together, we played sports, we also learned. We had two hours of study every morning.” Ramah, he said, “is in my blood.”

There were two features at camp that shaped his life. “Number one was the sense of meaning and joy in the Jewish tradition it fostered through all kinds of activities that were just fun as well as some serious discussions.” The second was that “it set up the structure for thinking seriously about life and moral issues.”

Ramah would also influence his personal life. In 1961, when he was 18, he attended a Ramah conference in the Poconos for counselors, where he met his wife, Marlynn. “She was from Philadelphia, and I dragged her back to Wisconsin, where we were counselors until 1964.” When Dorff and Marlynn moved to Los Angeles, he became the professor-in-residence at Ramah, where he stayed for 16 years.

One lesson that especially influenced him occurred when Dorff was 15. Rabbi David Mogilner, director of the Wisconsin camp, would meet with 15 and 16 year old campers every Monday. He asked how many keep kosher at home and out, then how many don’t keep kosher at all and finally, how many keep kosher at home but not out. The Dorff family fell into the last category. “It’s you people I don’t understand,” the rabbi said, “because you are inconsistent.” Reminiscing about this, Dorff said the rabbi “was basically saying why would anybody in his or her right mind do any of these Jewish things or believe in these Jewish things?” What truly impressed him was that “a rabbi who had devoted his life to Jewish tradition was not afraid, but eager to ask all kinds of questions that would undermine the system. Until then, I had assumed Judaism was something you did because your family did it, tradition.”

At home, he was raised in Milwaukee, Wisconsin by supportive parents he described as “typical second-generation” Jews. Both grew up in Orthodox synagogues and later joined Conservative synagogues. “My father put it this way,” said Rabbi Dorff. “‘I didn’t leave Orthodoxy, it left me because it wasn’t modern.’”

But at 15, he made a decision that would change his life. “If I was going to be religiously Jewish, it came at a real social cost,” he said. Friday night basketball games vanished. After a Saturday night movie, everyone would head to the Big Boy, with its famous cheeseburgers. Dorff ordered salad or a fish sandwich. His non-Jewish friends thought it was cool, showing he had principles. His Jewish friends told him it was medieval.

By college, he had made up his mind to become a congregational rabbi and teach on the side. After gaining a doctorate in philosophy, Rabbi Dorff was thinking about his first congregation. When a teaching position beckoned at the University of Judaism, the president, Rabbi David Lieber, convinced Dorff to come out and interview. “Before Marlynn and I came out in November 1969, I never had been west of the Mississippi,” Dorff said. “After Rabbi Lieber had me teach a few classes, he asked what I thought.” When the young rabbi repeated his intention of being a congregational rabbi and teaching on the side, Lieber had a two-tiered response.

He told Dorff he should start with the academic piece because academics earn less than congregational rabbis, and it’s always easier to go from less to more. Finally, Lieber told him, in congregations many will compliment you while in academia they are rare. Better to start with fewer. “Those,” said Rabbi Dorff, “were the two winning arguments that brought us to Los Angeles in 1971. I figured I would be here two or three years, then take a congregation in the Midwest. Fifty-three years later, I have yet to get serious.”

“To be a serious Conservative Jew, you need a serious commitment to the tradition and also a serious commitment to the modern world, and you have to integrate them.”

He did get serious when asked what people don’t understand about Conservative Judaism. “It’s not Goldilocks, not too warm, not too cold,” Dorff said. “It is the middle movement, but it is a serious commitment to a form of Judaism that is traditional and also open to the outside world so that the way we practice our tradition is informed by science, literature, economics, politics and everything else. To be a serious Conservative Jew, you need to understand both, a serious commitment to the tradition and also a serious commitment to the modern world, and you have to integrate them.”

Fast Takes with Rabbi Dorff

Jewish Journal: Your favorite time of the Jewish year?

Rabbi Dorff: Shabbat.

JJ: What superpower would you like to have?

Rabbi Dorff: To make this the Messianic world in which there is no war or want or fear or sickness.

JJ: Your favorite Jewish food?

Rabbi Dorff: Potato kugel.