To view previous dispatches, click here.

SPRINGFIELD, Ohio – Earlier this year, a young Haitian-American walked through the doors of First Diversity Staffing Company LLC here on E. High Street, angry. To her shock, the IRS claimed that the U.S. citizen had earned about $20,000 during her employment with First Diversity. But, in reality, she had only worked two-and-a-half weeks as a Haitian Creole translator on the assembly line at KTH Parts Industries Inc. in nearby Saint Paris, Ohio, earning much less in wages with a pay of $19.90 per hour. Someone at First Diversity had allegedly stolen her social security number and used it for another employee without a number, say people familiar with the situation.

Before that, one Friday morning in early 2021, about a dozen Haitian migrant workers stormed through the doors of the staffing agency, shouting angrily in their native French Creole.

“Nap vòlè kob mwen!” one worker shouted. “You are stealing my money!”

“First Diversity, nou vòlè!” another yelled. “First Diversity, you are thieves!”

They demanded answers for why they hadn’t been paid their full wages for making sandwiches, like turkey cheese subs, in near-freezing conditions at the Classic Delight LLC factory, an hour away off I-75 North in little St. Paris, Ohio.

The workers, desperate and distraught, showed front-desk staffers photos of their time cards and the hours they had worked that had not been paid.

Instead of a quick resolution, the workers were met with empty promises, deflection and outright dismissals by senior leaders, sources say — a pattern in a larger, unchecked system of alleged abuse and greed that has allowed First Diversity to thrive off the backs of vulnerable Haitians. In reporting for the Pearl Project, a nonprofit investigative reporting initiative, I have learned that federal and state investigators from the FBI and the office of Ohio Attorney General David Yost have now widened their probes into alleged human trafficking by the company to also look into alleged identity theft, with the apparent theft of social security numbers, and alleged immigration, tax, wage and employment fraud.

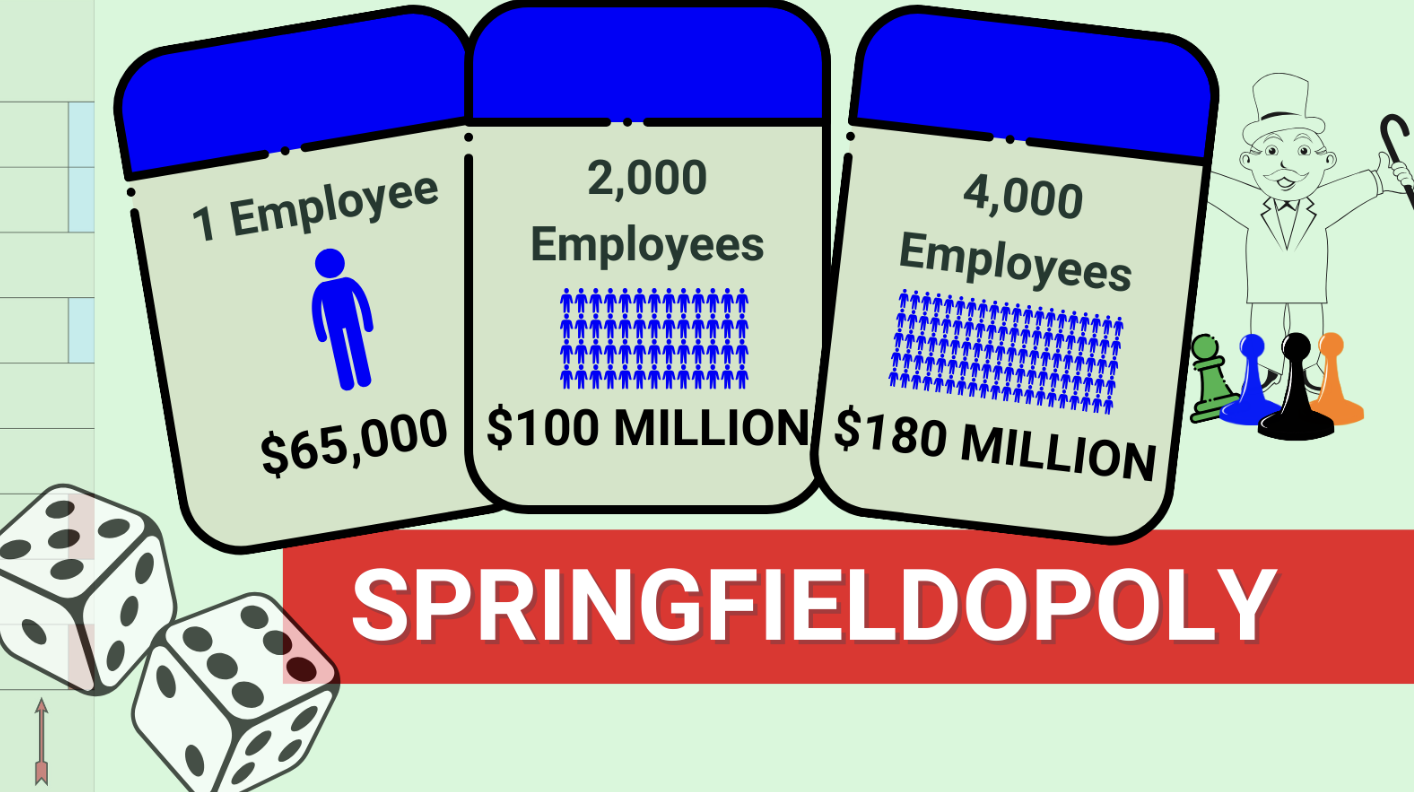

Among other exclusive details, sources tell me that the president of the company, George Ten, nicknamed “King George” for his lavish lifestyle, has built an empire off the backs of mostly migrant workers, raking in a shocking amount of annual gross revenues: an estimated $180 million – almost four times the city’s annual revenues.

I’ve learned that Springfield City Manager Bryan Heck was warned about the alleged trafficking as far back as the summer of 2019 at a meeting at Winans Coffee and Chocolate on N. Fountain Avenue, but he told me via email that he doesn’t remember such a meeting. By late 2019, the warnings also reached Mike McDorman, the longtime president of the Greater Springfield Chamber of Commerce, and he similarly took no action. The Chamber of Commerce president didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Byran said he does remember getting a warning from a former First Diversity employee in September 2023 and took action. For this story, a hometown where people are on first-name basis, I’ve chosen to use the same naming convention.

“An investigation of illicit business practices and potential human trafficking began in September of 2023,” Bryan said, “and a formal request for additional support and resources was made to the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation on October 25th per my direction.”

Today, however, it is business as usual at First Diversity, according to sources. What workers don’t know: behind the front desk is an open office space, named the “Monopoly Room,” where First Diversity staffers tally “orders” from employers who have vacant spots for workers. First Diversity officials call workers “products,” say sources. Last week, I sat in the “Monopoly Room” as the company defended its business practices.

Indeed, First Diversity leaders were so taken with the Monopoly game theme that over the years, they promoted the company’s work on Instagram as a game of “Springfieldopoly,” but for whistleblowers – hopeful when they walked in to work at the company and traumatized when they left – the business has not been a fun family activity around a cozy fireplace with hot chocolate and marshmallows, but rather an allegedly fraudulent business that has gone unchecked and reaped millions from the work of vulnerable migrant workers. Early reporting reveals that the issues in Springfield speak to dynamics of power and alleged exploitation in towns throughout America.

Over five years, a disturbing narrative emerged: a business built on greed and alleged exploitation while business and political leaders ignored the festering problems, resulting in the maelstrom that has upended the city now.

“They knew,” said one whistleblower.

The Play: First Diversity’s ‘Springfielopoly’ Rakes in an Estimated $180 Million

Since arriving in town 10 days ago, I have interviewed about100 people, studied scores of court, property and traffic documents and walked thousands of steps from E. High Street to Ferncliff Cemetery and Arboretum for my ongoing investigation into what’s really happening in Springfield. I began this project through my non-profit investigative group, the Pearl Project, named after my friend, Daniel Pearl, kidnapped and murdered in Pakistan while reporting for the Wall Street Journal. This is the second in the series.

My first piece looked at the allegations by former president Donald Trump and his running mate, J.D. Vance, a Republican senator from Ohio who made the initial claim that Haitian migrants to Springfield are eating the cats and dogs in Springfield. I haven’t found evidence regarding the largely debunked allegations but I learned the story here is not about cats and dogs but about mules who engage in the alleged business of labor trafficking.

After my piece was published in the Jewish Journal, I began to hear from many of the town’s residents, Haitian immigrants, whistleblowers, city and state officials and law enforcement, corroborating my story and offering additional information.

With their help, including two mothers with whom I chat in a text group we call the “Nancy Drew Crew,” I have been able to piece together the minutest details of this intricate alleged underground network of exploitation of Haitian migrants by Haitians who “King George” hired and compensated for their roles as recruiters, transporters and hustlers. But the exploitation went far beyond affinity-based trafficking to include a circle of civic and business leaders who, at best, turned a blind eye to the warnings and, at worst, are potentially complicit, in a scandal from which the city and moneyed business interests profited.

Now, thanks to these brave whistleblowers coming forward through this investigation, state and federal officials have launched probes into the alleged human trafficking and fraud operation built by George and his cronies.The full impact of First Diversity’s alleged exploitation is felt far beyond its offices. Some of the whistleblowers cried, recounting their experiences working at First Diversity. Workers spoke of paychecks that never arrived, long hours with no overtime and promises of stability that quickly turned to dust. Some, like the 24-year-old woman and her mother, had their Social Security numbers allegedly stolen, while others found their I-9 forms and drug test results faked to keep them in the system.

Ignorance is no excuse for the town’s leaders, say many of the whistleblowers.

Last week, after publishing my first dispatch from Springfield, chronicling allegations of human trafficking, George and three of his senior executives sat down with me in an extensive interview in their offices on E. High Street, walking through the history of the company, George pushing my chair in when I went to sit down. This week, George answered questions via email, taking a slightly more aggressive tone. On the expanded investigations by state and federal authorities, he wrote: “These are false, unverified, libelous allegations of criminal activity. We have not been notified of an investigation by the AG,” Attorney General Yost. That’s typical because investigations can take weeks if not months.

Company representatives told me the average contract worker at First Diversity works 44 hours a week, earns an average pay of about $1,000 per week, and the company employs “between 1,800 and 2,000 associates,” with an average number of 1,870 employees.

Throwing Doubles and Advance to Go: Funny Math At First Diversity

The math doesn’t add up: $17 x 40 hours = $680. The average pay of $1,000 – $680 = $320. Overtime is time-and-a-half, or $25.50. So, $320 ÷ $25.50 = 12.5 hours overtime hours.

What is little discussed is the “fee” staffing firms charge for their recruiting and placement services, which is about 30 percent of wages – not to mention revenue from housing, transportation and other services that George arranged through First Diversity and contractors.

At an average wage of $17 per hour and an average of four hours of overtime paid at the usual rate of a time-and-a-half, or an average of $25.50, it would only take 4,000 workers to build an empire with the estimated annual gross revenues of $180 million. Either George is underreporting his number of workers, their pay and overtime or another revenue stream.

Asked about criticism that the company grew off the backs of vulnerable Haitian migrant workers, George responded via email: “We are a successful business that connects people with jobs. We improve the lives of Haitian migrant workers, which is why they keep working with us.”

In response to the criticism by the former employee that she didn’t earn as much money as reported by First Diversity to the IRS, George responded: “The average salary our employees receives [sic] is $17 on the hour. We are committed to our employees and when issues arise, we always work with our employees to resolve them…as quickly and completely as possible.”

George offered an identical response on the complaints by the Classic Delight employees. The average salary our employees receives [sic] is $17 on the hour. When there are issues, we do our best to resolve them as quickly and completely as possible.

First Diversity’s Perspective: ‘We’re Truly Helping this Community’

After I published my first column last week, First Diversity defended their hiring and payment practices and launched a public relations charm offensive that included the sit-down interview with me. Unable to reach George by phone, I walked into First Diversity’s offices on E. High Street to ask for an interview. George’s team – led by his wife, Rachael Ten, invited me to return for an interview the next day at noon. Earlier this week, George invited reporters from the Dayton Daily News to the office, and they just published George’s denials of “mistreatment in work, housing realms,” along with photos of a beaming George and Rachael Ten. The Springfield News-Sun reprinted the story.

I arrived, passing a worker fixing a stone wall that a Haitian driver, new to the United States and unfamiliar with its roads, had crashed into, cementing the stereotypes of critics. George met me in the reception room with a warm smile. He is 5’4 and 190 pounds, according to his driver’s license data from a parking ticket. He led me through a short hallway that runs through the middle of the office to a glass conference room and a seat in the middle of a small conference table, helping to then guide my chair under the table.

The glass conference room sat across the hall from a larger room where several staffers work: the Monopoly room with posters from the game.

Keen to reshape the narrative around their company, Rachael, an executive at First Diversity and George’s wife, sat to my left. Later, via email, when I asked George her title, he responded: “Back Office Operations.”

Raising some concerns, amid the allegations of labor trafficking, identity theft and employment, immigration and tax fraud, Rachael has been a member of the Ohio Air National Guard since 2004, according to an Ohio Air National Guard spokesperson. She is a master sergeant in the Ohio Air National Guard and serves as a drill status guard member, the spokesperson said.

Also at the table, Bruce W. Smith, 54, his senior executive vice president, sat across from me. Bruce said his children, now adults, were “surprised” and “confused’ by the allegations their father’s company is orchestrating an alleged trafficking operation. A Springfield native, sources say Bruce and George are the yin and yang of First Diversity: Bruce presents himself as the softer “good Christian” to George’s more hard-edged demeanor, butting heads often with George but remaining loyal to him and the company and using his connections and good will to smooth over any issues that might disrupt George’s operations.

An executive who just introduced himself as “Jay,” sat off a bit in the corner, taking notes. “Jay” arrived in Springfield in 2007 and worked at a “large big box staffing company” for 14 years until January 2020 when he was let go, arriving then at First Diversity in March 2020 from a “very compliant background,” Bruce said. When I asked for his full name later, George responded via email: “Out of respect for our employees privacy, we are declining to answer.”

George gave me permission to record the interview but not videotape it, and he didn’t want me to take pictures of them but I was allowed to take photos of community awards they got over the years. George said, “We’d love to be able to share our side and how we’re truly helping this community,” “how this community came to be and how we continue to help this community.”

I asked George about his origin story, first sharing mine, arriving in New Jersey as an immigrant from India and then moving to Morgantown, W.V., another small town in America, very similar to Springfield. Soft spoken and measured, George said he was born at Union Hospital in the Bronx, growing up in New York, “running around Jersey, Route 1, northern Jersey, the Oranges,” his parents immigrants to the U.S. from Puerto Rico, living in the Bronx and working in the garment district in Manhattan in the 1940s and 1950s.

His father, Miguel, moved to Delaware to work for a manufacturer and then moved to Springfield to work human resources for Dole. Earning a BA and MA in human resources at a local Christian college, Cedarville, George described his own rise from a humble background to a leadership role in the Army, where he served in Iraq handling logistics. A U.S. Army spokesperson said George was a motor transport operator in the U.S. Army Reserve from August 1999 to March 2008, deploying to Iraq from January 2004 to January 2005 and leaving the U.S. Army Reserve with the rank of sergeant.

On Sept. 20, 2002, Miguel incorporated First Diversity Staffing Group Inc. in Delaware with an address on another part of E. High Street. In 2008, he incorporated it in Ohio, records show, and Miguel told me earlier that he gave George the business around 2010 “because the Lord called me to be a pastor.”

“Most immigrants, they were told that the streets in New York City were paved with gold,” he said, leaning forward and looking me in the eye. “Not only were they not paved with gold, they were not paved, and they were the ones going to be doing the paving.”

George added,“We get the immigrant story because my family’s a big part of that, coming from another country, coming to a new city, a new culture, not speaking the language, being abused for not speaking the language. He concluded by saying, “So we get it. I’m first-generation immigrant to an immigrant family.”

George and his team carefully calibrated their responses to my questions, presenting him as a community benefactor not an alleged human trafficker.

His wife and the two executives nodded in agreement as he painted the picture of benevolence and opportunity. They offered a series of curated success stories about workers who had supposedly thrived under First Diversity’s guidance.

‘Make Positivity Louder’ and ‘Look for the ‘Yes’

George portrayed himself as a savior, positioning his company as the bridge between marginalized communities and the American dream.

“We understand the immigrant plight. We’re not here to take advantage of that anyway. We’re here to assist, make opportunities louder, make positivity louder. And that’s why you continue to see people always stop at First Diversity. We’re the first stop for employment for this community because of the…way we speak to them and the dignity, I think, they feel while working with us. We’ve lived it ourselves. My parents, my grandparents lived it.”

However, the whistleblowers said that inside First Diversity, exploitation allegedly extended beyond low pay and long hours. They alleged that a staffer had stolen Social Security numbers from workers, compromising their identities and using their information without consent. Other staffers told me they faked drug test results and a form called the “I-9,” which the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services uses to verify a person’s eligibility to work in the United States.

George denied the charges, saying: “Every individual that we hire is documented,” to legally work in the U.S. Rachel denied any falsification of records. “That’s not something we’re aware of or have record of.”

The staffers told me they would be coerced to accept false documents to keep undocumented workers in the company’s electronic database, powered by Avionté Staffing Software, a global platform based in Bloomington, Minn. Sometimes a translator would help a worker fill the I-9 form with fraudulent documents, and company leaders intimidated and coerced recruiters to sign off on the I-9, knowing the documentation was fraudulent.

In Ohio, companies aren’t obligated to upload documents to E-Verify, a system run by the Department of Homeland Security that is supposed to confirm a person’s employment eligibility through the Social Security Administration. A state legislative effort, H.B. 327, to mandate E-Verify passed the state House in June but didn’t get through the state Senate. First Diversity workers don’t get paid through direct deposit into bank accounts, but rather through a debit card system called “rapid! PayCard,” run by Rapid Finance, based in Bethesda, Md.

Bruce said: “The folks we send out, we have E-Verify receipts on.” Whistleblowers say those “receipts” have false information. “What we do now is we find companies that need a workforce. We build programs.” He continued: “If you are legally allowed to work in the United States and you pass the background checks that the client has given us – the filters, we are more than happy to give you an assignment, be it from Springfield, Ohio, be it from Port de Prince,” Haiti.

Waiting his turn to speak, George said he was proud of a program that hires people formerly in prison for crimes. “We look for the yes,” he said, earnestly. “We’re looking for the yes in people.”

I was confused and asked: “What does that mean: ‘the yes’?”

“We’re looking past their past. We’re looking for reasons to hire them, not reasons not to hire them.”

“So that they’ll say, ‘Yes,’ or you’ll say, ‘Yes’?” I asked.

“So, we’ll say yes and maybe place ‘em somewhere,” he said. “We’re looking to make positivity louder. We’re looking to help these folks.”

Speed Die Rules: Allegedly Stolen Data, Faked Identities, False Drug Results

Inside First Diversity, exploitation allegedly extended beyond low pay and long hours. Monopoly was both their theme and ethos. “Speed die” is a way to play the game faster with quicker payouts, and that is what they did, whistleblowers say.

Multiple whistleblowers alleged that a staffer had stolen Social Security numbers from workers, compromising their identities and using their information without consent. Other staffers told me they faked drug test results and a form called the “I-9,” which the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services uses to verify a person’s eligibility to work in the United States.

George denied the charges, saying: “Every individual that we hire is documented,” to legally work in the U.S. Rachel denied any falsification of records. “That’s not something we’re aware of or have record of.”

What George was relating was in stark contrast to testimonials I heard from many former employees, many of them young women hired in their early 20s, still processing months and years later serious trauma they said they experienced being coerced to break the law and punished when they pushed back.

An Abrupt Shift: From Local ‘Nightmare’ Hires to Compliant Migrant Pool

In early 2019, First Diversity had a lot of Hispanic clients, but it also seemed to hire consistently from the local Springfield community, featuring a stock image on its social media feed of a man who could have been a Springfield native with the simple message: “Get HIRED today!”

The target market for workers changed abruptly that year, sources tell me, as the company started tapping a new earnings potential: migrant workers from Haiti, people familiar with the company told me.

Rachael took exception to that characterization. “Let’s be clear with that, please,” she said. “The focus has always been the community of Springfield. Our focus is here.”

Except company executives admit that a shift to Haitian workers happened in 2019. They said they were responding to a call by the Springfield Chamber of Commerce for workers and “orders” by employers for employees and, as one First Diversity executive, “Jay,” put it, local hires were a “nightmare.”

Rachael explained that an Indianapolis client started laying off First Diversity’s Haitian workers after an acquisition, sending the workers to Springfield to look for work. “We had to find more business,” she said. “And this is where we started working with the Haitian community.”

Bruce named the company – Kyoto or Cato or something similar – during the interview but when I checked back to confirm its spelling, George responded, via email: “We do not release the names of our past or current clients.”

“That’s the genesis of the story,” said George. “So, there’s a small group of Haitians working in Springfield. They’re gainfully employed. And then what happened next would be political or be policy.”

He turned it over to “Jay.” First Diversity was focused on “what we would call locals,” Jay said.. “So people that lived here locally. It was a nightmare.”

“Trying to get people to go to work. We would get somebody to go to work, they would turn over to 50 percent rate attendance every day. We’d have 20 percent of our population missing. We couldn’t build jobs because of background problems. A lot of it was drug screening problems. They wouldn’t go to work,” said “Jay.”.

The vilification of the local worker had begun. Maybe there was some truth to it, but this narrative had become the callous go-to to explain why First Diversity officials and other business leaders churned migrant workers from Haiti through jobs.

Call for Jobs from a ‘Fantastic’ Chamber of Commerce

Around then, in April 2019, George attended the Springfield Chamber of Commerce Business Expo, snapping a photo of himself with the president of the Greater Springfield Chamber of Commerce, Mike McDorman, a bouquet of red, gold and silver balloons floating behind them.

“So there’s all this uproar in the community about how we need better jobs in Springfield, right?” “Jay” asked. “Springfield has a fantastic Chamber [of Commerce]. One of the best in the nation.”

“Mike McDorman is fantastic,” “Jay” continued.

McDorman wanted jobs for new businesses in the area. He knew First Diversity was filling them, say people familiar with the hiring.

Indeed, “Jay” said, about the time when Haitian workers were coming here from the Indianapolis assignment and employers were unable to fill jobs with local workers, “the Chamber [of Commerce] goes out and says, ‘Fine, we’re going to get the jobs.’”

George interjected: “And they did that.”

This started in 2019 as men in unmarked white vans started heading to Florida from First Diversity’s offices to bring workers from Haiti to Springfield, say sources.

“Jay” continued: “Chamber brings the jobs to Springfield. The locals still did not go to work.”

Among the employers, “Jay” said, were Topre America Ohio, which opened a facility on Reaper Avenue in the manufacturing section and Gabriel Brothers Inc., a discount clothing distributor, which opened a distribution center on E. Battlefield Road. (Interestingly, Gabe’s as it’s called was started by the family of one of my high school classmates in Morgantown, W.V.).

Empty Community Chest: “They are Suffering Terribly.”

In a new church on Troy Road, on the northwest edge of Springfield, Jean André, a Haitian American pastor, took a visibly deep breath when I asked him about First Diversity. Pastor Jean started the first Haitian church in nearby Columbus some years ago before the new migrant workers arrived, and he told me that newly arriving Haitian workers, working with immigration, employment, housing and transportation insecurity, have faced abysmal rental conditions and little power with First Diversity.

When he drove to Springfield, starting in 2019, to pick up First Diversity’s new migrant workers for church services in Columbus, he saw cramped, overcrowded housing conditions with rooms subdivided into sections, numerous men sharing one bathroom.

He said: “It is really a shame to see how they treat people as paid slavery. This is what I call it.”

“They are in hell while living on earth,” Pastor Jean continued. “You get my word? So that means they are suffering terribly. And the bad thing about it, when you are suffering terribly, you cannot do anything about it…when you are suffering, you don’t see how you can take yourself out of the situation, and you have to live it. This is horrible. This is what happened.”

For the Haitians migrant workers experiencing indignities, Pastor Jean said: “I call them heroes.”

In recent months, Springfield City Planner Bryan Heck has told the media and citizens, angry about traffic accidents and other issues by the new Haitian migrants, that he didn’t know how the new migrants had arrived in Springfield. However, as reported in my first dispatch, First Diversity started hiring migrant workers from Haiti in plain sight in 2019 in a new business strategy to build its coffers, and locals started warning city leaders that the new hiring wasn’t above board.

‘King George’ Demands: Fill the ‘Orders’ in the Monopoly Room

“Jay” said that “the perfect storm” was created with COVID and President Joe Biden’s election in 2020 and the renewal of the Temporary Protected Status program, which allowed workers to arrive from Haiti. “All these jobs are now open, but no one is going to work. Meanwhile, the population that was over in Indianapolis now doesn’t have work anymore. And they are displaced. They learn of a few people that are living here and working and they start coming” to Springfield.

George said, “The explosion really occurred when Biden’s policies enabled people to call their loved ones here. And that’s when…it just went vertical,” with an explosion in business.

George said with the Temporary Protected Status program, “People here really then started petitioning for their family members. There’s work here. There’s jobs. Not only there’s jobs, there’s affordable housing. So all those confluence of factors kind of created the situation we see now, which…”

“…the locals are calling the influx,” says Bruce, finishing the thought.

One day, “Jay” recalled, George called him into the conference room, with “orders out there on the board,” in the room called the Monopoly Room, of employers seeking workers. George said, “We got to figure out a way to get all these orders filled.”

“It came with finding the yes,” said “Jay.”

“You had a whole lobby full of people out there that have good paperwork,” who “want to go to work.”

Bruce continued: “And we have clients that need workers, clients that need people. So then we come up with a way to marry the two.”

They started a program to get the jobs filled but won’t tell me the name, citing “intellectual property.”

One reason the Haitians were quickly assimilated into the workforce is their discipline, drive and work ethic, First Diversity employees say. According to “Jay” when you compare the Haitian workforce to your local workforce, the turnover is minimal,” losing one or two Haitaian workers a month, versus losing 40 to 50 local hires a month.

“On any given day, about 20 of your workforce is sick, has a car problem hung over, whatever. I don’t know,” Jay continued. “But they’re not there. But this workforce, on any given day, 99 percent of our folks are at work and the turnover rate is between three and five percent.”

Advance to Go: Leveraging Christ and ‘The Gathering’

In late May 2019, as First Diversity was making a strategic switch to bringing Haitian workers to Springfield, George bought a table at a high-profile event for a new organization that had come to town: “The Gathering,” or more specifically “The Gathering of the Miami Valley,” an exclusive club started for “men who have been transformed by Christ,” according to its mission statement. Its members include many of Springfield’s most powerful city officials, business tycoons and community leaders, meeting in exclusive “Locker Rooms” where men form “deeper relationships.”

In a photo posted to First Diversity’s Instagram page, George beamed with his wife, Rachael, as they stood next to a former NBA basketball player, Clark Kellogg, and George’s senior executive vice president, Bruce W. Harris, stood on the other side of the former NBA star, grinning.

King George’s empire-building didn’t just rely on the staff he hired to bring in Haitians workers. It was allegedly fortified by a well-connected network of political and business elites – mostly men – who insulated him and his business from scrutiny.

Years earlier, the Springfield Chamber of Commerce president, McDorman, shared a LinkedIn post from The Gathering’s Fall Breakfast, featuring a talk by the author of a book, “Lead…for God’s Sake.” McDorman didn’t return requests for comment.

First Diversity’s certified public accountant, Steve Stuckey – business partners with the company’s senior executive vice president, Bruce, in a rare coins enterprise – is one of The Gathering’s “governing board members” along with Springfield’s city manager, Bryan. Years later, the city’s mayor, Rob, a member of The Gathering, filmed a short YouTube video for the group, putting on a Burger King paper crown to share that he was “the king of misunderstanding my capacity.” Steve didn’t return a request for comment. The Gathering’s executive director, Jeff Pinkleton, didn’t return a request for comment.

Asked if Bruce and Steve were able to leverage their friendships and community clout to deflect scrutiny of First Diversity’s operations, George answered, via email: “The question hints at, [sic] some unspecified illegal activity and is therefore libelous.”

Bryan, the city manager, said in a written statement, “I have served on the Board of the Gathering since January 2023. This is a non-titled board position to discuss the ministry which is about connecting men to men and men to God. I have never discussed First Diversity with Mr. Stuckey. I do not have any personal affiliation or friendship with Bruce Smith and the assertion around leveraging their connections to protect illicit business practices through this organization or Board is completely untrue.”

Karen Graves, strategic engagement manager for the City of Springfield, wrote back to my query, and said: “I was able to reach the Mayor and he confirmed that he does participate in a Gathering Group of Christian fellowship but his particular group does not include Bruce, Bryan or Steve. There are various gathering groups (around 10).”

Karen added: “Mayor Rue also wants to stress that he has not acted in any way to protect any illicit business practices. It is absolutely baseless and untrue.”

By the summer of 2019, employees at First Diversity started swapping stories about the shady work they were expected to do, through alleged bullying, coercion and intimidation, sources said. That’s when Bryan, the city manager, was warned about alleged labor trafficking by First Diversity, although he doesn’t recall the meeting at Winans Coffee and Chocolate.

Through a spokeswoman, he sent me a written statement, saying, “I am not aware of a meeting at Winans in the summer of 2019 regarding this topic or matter. Additional context would be needed to understand who the conversation was with.”

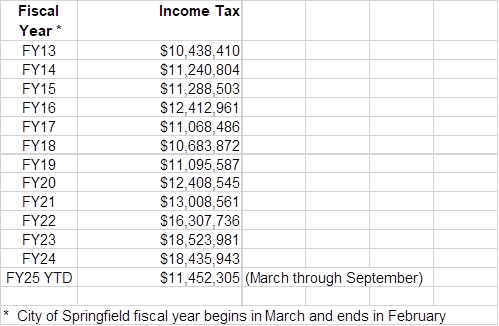

Income Tax: Catnip for City Leaders, Turning a Blind Eye

One of the reasons city leaders may not have wanted to question the new hiring boom: most of the city’s revenues come from income tax that employers pay the city.

In a 2019 report, the city’s then-finance director, Mark Beckdahl, explained the city levies a tax on “all wages, salaries, commissions and other compensation paid by employers,” as well as the net profits of businesses or professionals. City residents also must pay city income tax on income earned outside Springfield.

Indeed, after three years of declines, income tax revenue collected by the city steadily increased every year, except for in 2024, when it stayed about even, according to a chart that Ramona Metzger, director of the city’s office of budget and management, sent to me.

By November 2020, Bryan released a 2021 preliminary budget report and wrote that the “largest source of revenue” for the city’s general fund “continues to be income tax,” accounting for 75 percent of the city’s general fund.

Bryan wrote that year that “it is expected” the city would see “revenues from employment gains at Topre America Corp. and Silfex, Inc., and general improvement in the Springfield economy.” The next year, he made the same prediction, adding an employer, Gabriel, to the list, with the opening of a distribution facility not far from Dole.

Who provided many of the workers for these jobs? First Diversity. A spokeswoman for Silfex said: “Silfex does not have, and has never had, any direct association with First Diversity Staffing.”

Rental Properties: Getting the Haitians Coming and Going

In the game of “Springfieldopoly,” just like the real monopoly, the name of the game seems to be buying rental properties.

Between June 10, 2021, and June 30, 2021, as Haitian workers flooded into town, the town’s mayor, Rob Rue, bought seven properties on N. Limestone Street, E. Madison Avenue and Mason Street for a total cost of $1.78 million through a company, Littleton Properties of Springfield LLC, according to property records.

In recent weeks, as the purchases became public, raising criticism in the community, Mayor Rob said he rents the homes to Haitians, but says he rents them at market rates. Whatever the case, he, too, has been quietly profiting from the influx of low-wage labor. He has said he has done nothing wrong.

It was a growing pattern in Springfield.

Landlords have benefited from the cheap, exploitable workforce while publicly distancing themselves from the harsh realities faced by the workers.

For George and Bruce, the new wealth meant new prosperity for them. After the boom in business from the Haitian workers, George gave Bruce a used Maserati sports car as a gift.

On Jan. 19, 2022, George bought a mansion for $1.35 million on Pawleys Plantation Court in nearby Beavercreek, Ohio, using an LLC with the address of the house in its name. In our sit-down interview, George said he bought it for his family and parents as a “dual family home.”

Some months later, on June 21, 2022, Bruce bought a 35.3-acre farm just outside Springfield for $580,000.

Asked about this new wealth, George responded via email: “We are a successful business that connects people with jobs.”

There was not one peep about the new migrants from Haiti in the city’s annual reports until the 2023 annual report, which included a short article about the Clark County Department of Job and Family Services, headlined, “Demand Increased With Haitian Influx.”

The report said the agency, which is funded by taxpayer dollars, “saw the caseload of Haitian Creole immigrants increase dramatically, presenting new challenges for agency staff and resources.”

It noted that the “BenefitsPlus division saw more than 1,400 individuals receive Refugee Cash Assistance worth more than $2.2 million,” or about $1,571 per person.

A Town at a Crossroads: Empty Promises and Dwindling Paychecks

Despite the billions flowing through the staffing industry, safeguards for workers are alarmingly weak. Federal and state labor laws exist, but they are rarely enforced against staffing firms operating in this shadowy space. Instead, local officials often look the other way — or worse, they are complicit in the alleged racket.

In Springfield, where railroad crossings dot the town, much like the game of Monopoly, this cozy relationship between local elites and staffing firms raises uncomfortable questions.

Who is protecting these workers?

Why are the laws meant to safeguard against exploitation failing so completely?

It’s a system where everyone profits — except the workers, who bear the brunt of the abuse. The staffing firms get their markups, the companies get cheap labor, and the local landlords collect rent. The workers, meanwhile, are left with empty promises, dwindling paychecks, and little hope for a better future.

The staffing industry is a hidden behemoth within the American economy, generating billions in revenue while trying to satiate the seemingly unending labor needs of companies located in Springfield and nationwide, fueled by a burgeoning economy and lack of sufficient manpower. And it highlights an oxymoron: while some want to stem the tide of immigrants, the country’s economy – as it is currently set up – would suffer immeasurably without them.

The industry thrives on a simple model: companies turn to staffing firms to meet their labor demands, often for low-skill, high-turnover jobs in manufacturing, assembly lines, and distribution centers. When a company says it needs 100 workers, a staffing firm like First Diversity steps in, promising to deliver the workforce and signing a lucrative contract that ensures a steady flow of labor.

The financial arrangement is straightforward but can quickly turn exploitative: staffing firms charge a markup—typically around 30 percent—on each worker. For example, for every worker paid $12 per hour, the staffing firm charges the client company $15.60, pocketing the difference. This markup allows firms to generate substantial profits. But for companies like First Diversity, the markup is just the beginning of the slippery slope to breaking the law. They routinely shave off hours, manipulate timecards and find every possible way to cut costs, all at the expense of their employees, sources say.

For those Haitian workers who were yelling in the office, demanding their rightful wages, the promise of opportunity turned into a nightmare. They were lured into a system that preyed on their vulnerabilities, exploiting their lack of legal status and limited English proficiency. That’s the definition of human trafficking. It’s no longer about chaining men and women in the hulls of ships. It’s about using coercion, intimidation, persuasion and affinity to build trust, then trick workers.

First Diversity offered jobs that seemed like a lifeline but quickly became chains of exploitation, say sources. George denies the allegation.

Complex Logistics, Clandestine Transactions, Shell Companies

In the interview, George said “at one point we did control” transporting Haitians to work. It became “too much” so “we outsource that to third parties.” He said: “We now farm that out to third parties to transport people to and from work.”

George claimed: “So, all these people are being paid via check. We’re paying taxes…”

Indeed, George’s company, First Diversity, undergirds Springfield’s shadow economy, which benefits everyone but the Haitians. In the conference room, where the executives met me, George showed me a Chamber of Commerce award the company got in 2010 for being the “Minority Owned Business of the Year,” next to a wooden turtle from Haiti.

However, at a city commission meeting in August 2023, when a local father, Mark Sanders, raised questions about alleged “indentured servitude” by First Diversity and George, one of the commissioners, David Estrop, asked him to share tips with Bryan, the city manager, who nodded in acknowledgment and fumbled with his microphone, saying nothing. With growing frustration over Bryan’s lack of explanations for how Springfield got into this mess, local citizens started using the moniker “Lyin’ Bryan,” for the city player. They then called Mayor Rue, “Mayor Rude” for his alleged stonewalling.

Around then, after the controversy had long emerged, Mike, the president of the Springfield Chamber of Commerce issued a statement from the Chamber of Commerce, saying, “We stand with the City of Springfield and Clark County amid the Haitian population surge to ensure the continued safety, stability and economic success of our community. Businesses are thriving in Clark County through collaboration with our members and local leaders.”

It was a punt.

Soon after, city officials finally responded to questions by locals and uploaded two PDFs on their website last year: “Clark County, Ohio Haitian Influx FAQs” and “Clark County, Ohio Haitian Entrant Benefits Fact Sheet.”

Last September, Bryan, the city manager, was warned again about First Diversity and alleged human trafficking after the citizens were in an uproar. He acknowledged that meeting.

He said, “I met with a former employee of First Diversity (who requests to be anonymous) in September of 2023 to discuss concerns with First Diversity practices after First Diversity was named after a Commission meeting. An investigation of illicit business practices and potential human trafficking began in September of 2023 and a formal request for additional support and resources was made to the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation on October 25th per my direction.”

By September of this year, the town turned upside down from alleged political and business malpractice, the narrative that city leaders wanted to build emerged unscathed. In an article headlined, “How Haitian immigrants fueled Springfield’s growth,” Reuters asked, “Why Springfield?” but only offered vague answers of “friends,” a “brother” and “word of good job prospects.”

Across town in his home, Sanders, the retired engineer, continues to gather information after ringing the alarm bell about First Diversity the year before.

He put his assessment bluntly: “King George is the Monopoly man. The question now is: will he go straight to jail?”

Fear and Hope: The Church Next Door

Throughout my reporting, trying to understand what the political and business elite knew and when they knew it, I have been deeply moved by the resilience of Springfield’s most vulnerable residents. Time and again, I have seen people who, despite having every reason to despair, remain doggedly hopeful, determined to bring their town right side up. Whether it’s the quiet strength of Haitian and American whistleblowers speaking their witness to me in long conversations in phone calls, dining table chats, churches, local cemeteries and the Kroger parking lot on E. Main Street.

One day, my phone dinged with a text from Charlie Drummond, a Springfield resident who has been living in quiet fear from the headlines he sees about voodoo, cats and dogs and bad driving. Haitians had just bought the church next door to his house on Troy Road on the west edge of town, and a flow of unfamiliar faces had him on edge.

Charlie has seen the darkest of events. In my second day of reporting, standing on his paved driveway, across from the church, he told me about the death of his younger brother to a fentanyl overdose and the suicide of his father on the eve of surgery that would have amputated his right leg. You can see his life in the etchings of the wrinkles on his face. He was terrified that this church would be another extension of the exploitation and confusion happening around him. In his text, he told me Haitians were moving into the church. I zipped over to find out more , walking to the door of the church to ask if I could meet their pastor.

That’s where I met the pastor, and spoke to him about the realities whistleblowers had witnessed. As we ended, I asked if Charlie could come over for a visit. He said yes. I walked with Charlie to meet the pastor, who greeted Charlie with open arms. The pastor didn’t shy away from the truth; he called out the labor market in Springfield for what he believes is: “paid slavery.” He spoke openly about the conditions he’d seen, the stories of his congregants who had been caught up in the trafficking ring, and the urgent need for change.

Charlie’s girlfriend, Cassie, joined us, and soon, the pastor’s wife, Josiane Andre, came over, welcoming them both with warmth and understanding. In a simple but powerful moment, the four of them shook hands and smiled widely, bridging the divide that fear had built, a gray-and-white cat, Pepples, strolling by. It was a reminder that even in the darkest of situations, human connection and community can spark hope. The courage of people like Charlie and the pastor, who faced their fears and reached out, is what keeps them going.

Each handshake, smile and story of resilience I’ve encountered along the way has reaffirmed my belief that the people of Springfield will survive the bomb threats, non-stop media coverage and pre-election political exploitation. Amid the chaos and corruption, there is still hope — a stubborn, unyielding hope that refuses to let this town be defined by scandal, whether it’s political or economic.

What is left to be seen is whether state and federal authorities will be able to stop the cycle of exploitation and corruption and land First Diversity in the “Go Directly to Jail” space of the high-risk game of Springfieldopoly or will First Diversity and King George invoke the “Get out of Jail Free” card and remain a dubious pillar of the Springfield economy?

Asra Q. Nomani is a former Wall Street Journal reporter and the founder of the Pearl Project, a nonprofit journalism initiative named for friend and colleague, Daniel Pearl. If you want to support this continued coverage, please donate to the Pearl Project at this link. Asra can be reached at asra@asranomani.com and @AsraNomani on the X platform and other social media platforms. She invites your tips, suggestions and feedback. She can also be reached at 304-685-2189. She is reporting on labor trafficking and immigration issues nationally and invites your tips. She will protect the confidentially of all sources. To read her collection of dispatches, go to JewishJournal.com/DispatchesFrom.

Exclusive: In a Game of ‘Springfieldopoly,’ ‘King George’ Built an Empire with Estimated Revenues of $180M, and Feds and State AG Now Expand Human Trafficking Probe into Alleged Identity Theft and Tax Fraud

Asra Q. Nomani

To view previous dispatches, click here.

SPRINGFIELD, Ohio – Earlier this year, a young Haitian-American walked through the doors of First Diversity Staffing Company LLC here on E. High Street, angry. To her shock, the IRS claimed that the U.S. citizen had earned about $20,000 during her employment with First Diversity. But, in reality, she had only worked two-and-a-half weeks as a Haitian Creole translator on the assembly line at KTH Parts Industries Inc. in nearby Saint Paris, Ohio, earning much less in wages with a pay of $19.90 per hour. Someone at First Diversity had allegedly stolen her social security number and used it for another employee without a number, say people familiar with the situation.

Before that, one Friday morning in early 2021, about a dozen Haitian migrant workers stormed through the doors of the staffing agency, shouting angrily in their native French Creole.

“Nap vòlè kob mwen!” one worker shouted. “You are stealing my money!”

“First Diversity, nou vòlè!” another yelled. “First Diversity, you are thieves!”

They demanded answers for why they hadn’t been paid their full wages for making sandwiches, like turkey cheese subs, in near-freezing conditions at the Classic Delight LLC factory, an hour away off I-75 North in little St. Paris, Ohio.

The workers, desperate and distraught, showed front-desk staffers photos of their time cards and the hours they had worked that had not been paid.

Instead of a quick resolution, the workers were met with empty promises, deflection and outright dismissals by senior leaders, sources say — a pattern in a larger, unchecked system of alleged abuse and greed that has allowed First Diversity to thrive off the backs of vulnerable Haitians. In reporting for the Pearl Project, a nonprofit investigative reporting initiative, I have learned that federal and state investigators from the FBI and the office of Ohio Attorney General David Yost have now widened their probes into alleged human trafficking by the company to also look into alleged identity theft, with the apparent theft of social security numbers, and alleged immigration, tax, wage and employment fraud.

Among other exclusive details, sources tell me that the president of the company, George Ten, nicknamed “King George” for his lavish lifestyle, has built an empire off the backs of mostly migrant workers, raking in a shocking amount of annual gross revenues: an estimated $180 million – almost four times the city’s annual revenues.

I’ve learned that Springfield City Manager Bryan Heck was warned about the alleged trafficking as far back as the summer of 2019 at a meeting at Winans Coffee and Chocolate on N. Fountain Avenue, but he told me via email that he doesn’t remember such a meeting. By late 2019, the warnings also reached Mike McDorman, the longtime president of the Greater Springfield Chamber of Commerce, and he similarly took no action. The Chamber of Commerce president didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Byran said he does remember getting a warning from a former First Diversity employee in September 2023 and took action. For this story, a hometown where people are on first-name basis, I’ve chosen to use the same naming convention.

“An investigation of illicit business practices and potential human trafficking began in September of 2023,” Bryan said, “and a formal request for additional support and resources was made to the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation on October 25th per my direction.”

Today, however, it is business as usual at First Diversity, according to sources. What workers don’t know: behind the front desk is an open office space, named the “Monopoly Room,” where First Diversity staffers tally “orders” from employers who have vacant spots for workers. First Diversity officials call workers “products,” say sources. Last week, I sat in the “Monopoly Room” as the company defended its business practices.

Indeed, First Diversity leaders were so taken with the Monopoly game theme that over the years, they promoted the company’s work on Instagram as a game of “Springfieldopoly,” but for whistleblowers – hopeful when they walked in to work at the company and traumatized when they left – the business has not been a fun family activity around a cozy fireplace with hot chocolate and marshmallows, but rather an allegedly fraudulent business that has gone unchecked and reaped millions from the work of vulnerable migrant workers. Early reporting reveals that the issues in Springfield speak to dynamics of power and alleged exploitation in towns throughout America.

Over five years, a disturbing narrative emerged: a business built on greed and alleged exploitation while business and political leaders ignored the festering problems, resulting in the maelstrom that has upended the city now.

“They knew,” said one whistleblower.

The Play: First Diversity’s ‘Springfielopoly’ Rakes in an Estimated $180 Million

Since arriving in town 10 days ago, I have interviewed about100 people, studied scores of court, property and traffic documents and walked thousands of steps from E. High Street to Ferncliff Cemetery and Arboretum for my ongoing investigation into what’s really happening in Springfield. I began this project through my non-profit investigative group, the Pearl Project, named after my friend, Daniel Pearl, kidnapped and murdered in Pakistan while reporting for the Wall Street Journal. This is the second in the series.

My first piece looked at the allegations by former president Donald Trump and his running mate, J.D. Vance, a Republican senator from Ohio who made the initial claim that Haitian migrants to Springfield are eating the cats and dogs in Springfield. I haven’t found evidence regarding the largely debunked allegations but I learned the story here is not about cats and dogs but about mules who engage in the alleged business of labor trafficking.

After my piece was published in the Jewish Journal, I began to hear from many of the town’s residents, Haitian immigrants, whistleblowers, city and state officials and law enforcement, corroborating my story and offering additional information.

With their help, including two mothers with whom I chat in a text group we call the “Nancy Drew Crew,” I have been able to piece together the minutest details of this intricate alleged underground network of exploitation of Haitian migrants by Haitians who “King George” hired and compensated for their roles as recruiters, transporters and hustlers. But the exploitation went far beyond affinity-based trafficking to include a circle of civic and business leaders who, at best, turned a blind eye to the warnings and, at worst, are potentially complicit, in a scandal from which the city and moneyed business interests profited.

Now, thanks to these brave whistleblowers coming forward through this investigation, state and federal officials have launched probes into the alleged human trafficking and fraud operation built by George and his cronies.The full impact of First Diversity’s alleged exploitation is felt far beyond its offices. Some of the whistleblowers cried, recounting their experiences working at First Diversity. Workers spoke of paychecks that never arrived, long hours with no overtime and promises of stability that quickly turned to dust. Some, like the 24-year-old woman and her mother, had their Social Security numbers allegedly stolen, while others found their I-9 forms and drug test results faked to keep them in the system.

Ignorance is no excuse for the town’s leaders, say many of the whistleblowers.

Last week, after publishing my first dispatch from Springfield, chronicling allegations of human trafficking, George and three of his senior executives sat down with me in an extensive interview in their offices on E. High Street, walking through the history of the company, George pushing my chair in when I went to sit down. This week, George answered questions via email, taking a slightly more aggressive tone. On the expanded investigations by state and federal authorities, he wrote: “These are false, unverified, libelous allegations of criminal activity. We have not been notified of an investigation by the AG,” Attorney General Yost. That’s typical because investigations can take weeks if not months.

Company representatives told me the average contract worker at First Diversity works 44 hours a week, earns an average pay of about $1,000 per week, and the company employs “between 1,800 and 2,000 associates,” with an average number of 1,870 employees.

Throwing Doubles and Advance to Go: Funny Math At First Diversity

The math doesn’t add up: $17 x 40 hours = $680. The average pay of $1,000 – $680 = $320. Overtime is time-and-a-half, or $25.50. So, $320 ÷ $25.50 = 12.5 hours overtime hours.

What is little discussed is the “fee” staffing firms charge for their recruiting and placement services, which is about 30 percent of wages – not to mention revenue from housing, transportation and other services that George arranged through First Diversity and contractors.

At an average wage of $17 per hour and an average of four hours of overtime paid at the usual rate of a time-and-a-half, or an average of $25.50, it would only take 4,000 workers to build an empire with the estimated annual gross revenues of $180 million. Either George is underreporting his number of workers, their pay and overtime or another revenue stream.

Asked about criticism that the company grew off the backs of vulnerable Haitian migrant workers, George responded via email: “We are a successful business that connects people with jobs. We improve the lives of Haitian migrant workers, which is why they keep working with us.”

In response to the criticism by the former employee that she didn’t earn as much money as reported by First Diversity to the IRS, George responded: “The average salary our employees receives [sic] is $17 on the hour. We are committed to our employees and when issues arise, we always work with our employees to resolve them…as quickly and completely as possible.”

George offered an identical response on the complaints by the Classic Delight employees. The average salary our employees receives [sic] is $17 on the hour. When there are issues, we do our best to resolve them as quickly and completely as possible.

First Diversity’s Perspective: ‘We’re Truly Helping this Community’

After I published my first column last week, First Diversity defended their hiring and payment practices and launched a public relations charm offensive that included the sit-down interview with me. Unable to reach George by phone, I walked into First Diversity’s offices on E. High Street to ask for an interview. George’s team – led by his wife, Rachael Ten, invited me to return for an interview the next day at noon. Earlier this week, George invited reporters from the Dayton Daily News to the office, and they just published George’s denials of “mistreatment in work, housing realms,” along with photos of a beaming George and Rachael Ten. The Springfield News-Sun reprinted the story.

I arrived, passing a worker fixing a stone wall that a Haitian driver, new to the United States and unfamiliar with its roads, had crashed into, cementing the stereotypes of critics. George met me in the reception room with a warm smile. He is 5’4 and 190 pounds, according to his driver’s license data from a parking ticket. He led me through a short hallway that runs through the middle of the office to a glass conference room and a seat in the middle of a small conference table, helping to then guide my chair under the table.

The glass conference room sat across the hall from a larger room where several staffers work: the Monopoly room with posters from the game.

Keen to reshape the narrative around their company, Rachael, an executive at First Diversity and George’s wife, sat to my left. Later, via email, when I asked George her title, he responded: “Back Office Operations.”

Raising some concerns, amid the allegations of labor trafficking, identity theft and employment, immigration and tax fraud, Rachael has been a member of the Ohio Air National Guard since 2004, according to an Ohio Air National Guard spokesperson. She is a master sergeant in the Ohio Air National Guard and serves as a drill status guard member, the spokesperson said.

Also at the table, Bruce W. Smith, 54, his senior executive vice president, sat across from me. Bruce said his children, now adults, were “surprised” and “confused’ by the allegations their father’s company is orchestrating an alleged trafficking operation. A Springfield native, sources say Bruce and George are the yin and yang of First Diversity: Bruce presents himself as the softer “good Christian” to George’s more hard-edged demeanor, butting heads often with George but remaining loyal to him and the company and using his connections and good will to smooth over any issues that might disrupt George’s operations.

An executive who just introduced himself as “Jay,” sat off a bit in the corner, taking notes. “Jay” arrived in Springfield in 2007 and worked at a “large big box staffing company” for 14 years until January 2020 when he was let go, arriving then at First Diversity in March 2020 from a “very compliant background,” Bruce said. When I asked for his full name later, George responded via email: “Out of respect for our employees privacy, we are declining to answer.”

George gave me permission to record the interview but not videotape it, and he didn’t want me to take pictures of them but I was allowed to take photos of community awards they got over the years. George said, “We’d love to be able to share our side and how we’re truly helping this community,” “how this community came to be and how we continue to help this community.”

I asked George about his origin story, first sharing mine, arriving in New Jersey as an immigrant from India and then moving to Morgantown, W.V., another small town in America, very similar to Springfield. Soft spoken and measured, George said he was born at Union Hospital in the Bronx, growing up in New York, “running around Jersey, Route 1, northern Jersey, the Oranges,” his parents immigrants to the U.S. from Puerto Rico, living in the Bronx and working in the garment district in Manhattan in the 1940s and 1950s.

His father, Miguel, moved to Delaware to work for a manufacturer and then moved to Springfield to work human resources for Dole. Earning a BA and MA in human resources at a local Christian college, Cedarville, George described his own rise from a humble background to a leadership role in the Army, where he served in Iraq handling logistics. A U.S. Army spokesperson said George was a motor transport operator in the U.S. Army Reserve from August 1999 to March 2008, deploying to Iraq from January 2004 to January 2005 and leaving the U.S. Army Reserve with the rank of sergeant.

On Sept. 20, 2002, Miguel incorporated First Diversity Staffing Group Inc. in Delaware with an address on another part of E. High Street. In 2008, he incorporated it in Ohio, records show, and Miguel told me earlier that he gave George the business around 2010 “because the Lord called me to be a pastor.”

“Most immigrants, they were told that the streets in New York City were paved with gold,” he said, leaning forward and looking me in the eye. “Not only were they not paved with gold, they were not paved, and they were the ones going to be doing the paving.”

George added,“We get the immigrant story because my family’s a big part of that, coming from another country, coming to a new city, a new culture, not speaking the language, being abused for not speaking the language. He concluded by saying, “So we get it. I’m first-generation immigrant to an immigrant family.”

George and his team carefully calibrated their responses to my questions, presenting him as a community benefactor not an alleged human trafficker.

His wife and the two executives nodded in agreement as he painted the picture of benevolence and opportunity. They offered a series of curated success stories about workers who had supposedly thrived under First Diversity’s guidance.

‘Make Positivity Louder’ and ‘Look for the ‘Yes’

George portrayed himself as a savior, positioning his company as the bridge between marginalized communities and the American dream.

“We understand the immigrant plight. We’re not here to take advantage of that anyway. We’re here to assist, make opportunities louder, make positivity louder. And that’s why you continue to see people always stop at First Diversity. We’re the first stop for employment for this community because of the…way we speak to them and the dignity, I think, they feel while working with us. We’ve lived it ourselves. My parents, my grandparents lived it.”

However, the whistleblowers said that inside First Diversity, exploitation allegedly extended beyond low pay and long hours. They alleged that a staffer had stolen Social Security numbers from workers, compromising their identities and using their information without consent. Other staffers told me they faked drug test results and a form called the “I-9,” which the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services uses to verify a person’s eligibility to work in the United States.

George denied the charges, saying: “Every individual that we hire is documented,” to legally work in the U.S. Rachel denied any falsification of records. “That’s not something we’re aware of or have record of.”

The staffers told me they would be coerced to accept false documents to keep undocumented workers in the company’s electronic database, powered by Avionté Staffing Software, a global platform based in Bloomington, Minn. Sometimes a translator would help a worker fill the I-9 form with fraudulent documents, and company leaders intimidated and coerced recruiters to sign off on the I-9, knowing the documentation was fraudulent.

In Ohio, companies aren’t obligated to upload documents to E-Verify, a system run by the Department of Homeland Security that is supposed to confirm a person’s employment eligibility through the Social Security Administration. A state legislative effort, H.B. 327, to mandate E-Verify passed the state House in June but didn’t get through the state Senate. First Diversity workers don’t get paid through direct deposit into bank accounts, but rather through a debit card system called “rapid! PayCard,” run by Rapid Finance, based in Bethesda, Md.

Bruce said: “The folks we send out, we have E-Verify receipts on.” Whistleblowers say those “receipts” have false information. “What we do now is we find companies that need a workforce. We build programs.” He continued: “If you are legally allowed to work in the United States and you pass the background checks that the client has given us – the filters, we are more than happy to give you an assignment, be it from Springfield, Ohio, be it from Port de Prince,” Haiti.

Waiting his turn to speak, George said he was proud of a program that hires people formerly in prison for crimes. “We look for the yes,” he said, earnestly. “We’re looking for the yes in people.”

I was confused and asked: “What does that mean: ‘the yes’?”

“We’re looking past their past. We’re looking for reasons to hire them, not reasons not to hire them.”

“So that they’ll say, ‘Yes,’ or you’ll say, ‘Yes’?” I asked.

“So, we’ll say yes and maybe place ‘em somewhere,” he said. “We’re looking to make positivity louder. We’re looking to help these folks.”

Speed Die Rules: Allegedly Stolen Data, Faked Identities, False Drug Results

Inside First Diversity, exploitation allegedly extended beyond low pay and long hours. Monopoly was both their theme and ethos. “Speed die” is a way to play the game faster with quicker payouts, and that is what they did, whistleblowers say.

Multiple whistleblowers alleged that a staffer had stolen Social Security numbers from workers, compromising their identities and using their information without consent. Other staffers told me they faked drug test results and a form called the “I-9,” which the Department of Homeland Security’s U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services uses to verify a person’s eligibility to work in the United States.

George denied the charges, saying: “Every individual that we hire is documented,” to legally work in the U.S. Rachel denied any falsification of records. “That’s not something we’re aware of or have record of.”

What George was relating was in stark contrast to testimonials I heard from many former employees, many of them young women hired in their early 20s, still processing months and years later serious trauma they said they experienced being coerced to break the law and punished when they pushed back.

An Abrupt Shift: From Local ‘Nightmare’ Hires to Compliant Migrant Pool

In early 2019, First Diversity had a lot of Hispanic clients, but it also seemed to hire consistently from the local Springfield community, featuring a stock image on its social media feed of a man who could have been a Springfield native with the simple message: “Get HIRED today!”

The target market for workers changed abruptly that year, sources tell me, as the company started tapping a new earnings potential: migrant workers from Haiti, people familiar with the company told me.

Rachael took exception to that characterization. “Let’s be clear with that, please,” she said. “The focus has always been the community of Springfield. Our focus is here.”

Except company executives admit that a shift to Haitian workers happened in 2019. They said they were responding to a call by the Springfield Chamber of Commerce for workers and “orders” by employers for employees and, as one First Diversity executive, “Jay,” put it, local hires were a “nightmare.”

Rachael explained that an Indianapolis client started laying off First Diversity’s Haitian workers after an acquisition, sending the workers to Springfield to look for work. “We had to find more business,” she said. “And this is where we started working with the Haitian community.”

Bruce named the company – Kyoto or Cato or something similar – during the interview but when I checked back to confirm its spelling, George responded, via email: “We do not release the names of our past or current clients.”

“That’s the genesis of the story,” said George. “So, there’s a small group of Haitians working in Springfield. They’re gainfully employed. And then what happened next would be political or be policy.”

He turned it over to “Jay.” First Diversity was focused on “what we would call locals,” Jay said.. “So people that lived here locally. It was a nightmare.”

“Trying to get people to go to work. We would get somebody to go to work, they would turn over to 50 percent rate attendance every day. We’d have 20 percent of our population missing. We couldn’t build jobs because of background problems. A lot of it was drug screening problems. They wouldn’t go to work,” said “Jay.”.

The vilification of the local worker had begun. Maybe there was some truth to it, but this narrative had become the callous go-to to explain why First Diversity officials and other business leaders churned migrant workers from Haiti through jobs.

Call for Jobs from a ‘Fantastic’ Chamber of Commerce

Around then, in April 2019, George attended the Springfield Chamber of Commerce Business Expo, snapping a photo of himself with the president of the Greater Springfield Chamber of Commerce, Mike McDorman, a bouquet of red, gold and silver balloons floating behind them.

“So there’s all this uproar in the community about how we need better jobs in Springfield, right?” “Jay” asked. “Springfield has a fantastic Chamber [of Commerce]. One of the best in the nation.”

“Mike McDorman is fantastic,” “Jay” continued.

McDorman wanted jobs for new businesses in the area. He knew First Diversity was filling them, say people familiar with the hiring.

Indeed, “Jay” said, about the time when Haitian workers were coming here from the Indianapolis assignment and employers were unable to fill jobs with local workers, “the Chamber [of Commerce] goes out and says, ‘Fine, we’re going to get the jobs.’”

George interjected: “And they did that.”

This started in 2019 as men in unmarked white vans started heading to Florida from First Diversity’s offices to bring workers from Haiti to Springfield, say sources.

“Jay” continued: “Chamber brings the jobs to Springfield. The locals still did not go to work.”

Among the employers, “Jay” said, were Topre America Ohio, which opened a facility on Reaper Avenue in the manufacturing section and Gabriel Brothers Inc., a discount clothing distributor, which opened a distribution center on E. Battlefield Road. (Interestingly, Gabe’s as it’s called was started by the family of one of my high school classmates in Morgantown, W.V.).

Empty Community Chest: “They are Suffering Terribly.”

In a new church on Troy Road, on the northwest edge of Springfield, Jean André, a Haitian American pastor, took a visibly deep breath when I asked him about First Diversity. Pastor Jean started the first Haitian church in nearby Columbus some years ago before the new migrant workers arrived, and he told me that newly arriving Haitian workers, working with immigration, employment, housing and transportation insecurity, have faced abysmal rental conditions and little power with First Diversity.

When he drove to Springfield, starting in 2019, to pick up First Diversity’s new migrant workers for church services in Columbus, he saw cramped, overcrowded housing conditions with rooms subdivided into sections, numerous men sharing one bathroom.

He said: “It is really a shame to see how they treat people as paid slavery. This is what I call it.”

“They are in hell while living on earth,” Pastor Jean continued. “You get my word? So that means they are suffering terribly. And the bad thing about it, when you are suffering terribly, you cannot do anything about it…when you are suffering, you don’t see how you can take yourself out of the situation, and you have to live it. This is horrible. This is what happened.”

For the Haitians migrant workers experiencing indignities, Pastor Jean said: “I call them heroes.”

In recent months, Springfield City Planner Bryan Heck has told the media and citizens, angry about traffic accidents and other issues by the new Haitian migrants, that he didn’t know how the new migrants had arrived in Springfield. However, as reported in my first dispatch, First Diversity started hiring migrant workers from Haiti in plain sight in 2019 in a new business strategy to build its coffers, and locals started warning city leaders that the new hiring wasn’t above board.

‘King George’ Demands: Fill the ‘Orders’ in the Monopoly Room

“Jay” said that “the perfect storm” was created with COVID and President Joe Biden’s election in 2020 and the renewal of the Temporary Protected Status program, which allowed workers to arrive from Haiti. “All these jobs are now open, but no one is going to work. Meanwhile, the population that was over in Indianapolis now doesn’t have work anymore. And they are displaced. They learn of a few people that are living here and working and they start coming” to Springfield.

George said, “The explosion really occurred when Biden’s policies enabled people to call their loved ones here. And that’s when…it just went vertical,” with an explosion in business.

George said with the Temporary Protected Status program, “People here really then started petitioning for their family members. There’s work here. There’s jobs. Not only there’s jobs, there’s affordable housing. So all those confluence of factors kind of created the situation we see now, which…”

“…the locals are calling the influx,” says Bruce, finishing the thought.

One day, “Jay” recalled, George called him into the conference room, with “orders out there on the board,” in the room called the Monopoly Room, of employers seeking workers. George said, “We got to figure out a way to get all these orders filled.”

“It came with finding the yes,” said “Jay.”

“You had a whole lobby full of people out there that have good paperwork,” who “want to go to work.”

Bruce continued: “And we have clients that need workers, clients that need people. So then we come up with a way to marry the two.”

They started a program to get the jobs filled but won’t tell me the name, citing “intellectual property.”

One reason the Haitians were quickly assimilated into the workforce is their discipline, drive and work ethic, First Diversity employees say. According to “Jay” when you compare the Haitian workforce to your local workforce, the turnover is minimal,” losing one or two Haitaian workers a month, versus losing 40 to 50 local hires a month.

“On any given day, about 20 of your workforce is sick, has a car problem hung over, whatever. I don’t know,” Jay continued. “But they’re not there. But this workforce, on any given day, 99 percent of our folks are at work and the turnover rate is between three and five percent.”

Advance to Go: Leveraging Christ and ‘The Gathering’

In late May 2019, as First Diversity was making a strategic switch to bringing Haitian workers to Springfield, George bought a table at a high-profile event for a new organization that had come to town: “The Gathering,” or more specifically “The Gathering of the Miami Valley,” an exclusive club started for “men who have been transformed by Christ,” according to its mission statement. Its members include many of Springfield’s most powerful city officials, business tycoons and community leaders, meeting in exclusive “Locker Rooms” where men form “deeper relationships.”

In a photo posted to First Diversity’s Instagram page, George beamed with his wife, Rachael, as they stood next to a former NBA basketball player, Clark Kellogg, and George’s senior executive vice president, Bruce W. Harris, stood on the other side of the former NBA star, grinning.

King George’s empire-building didn’t just rely on the staff he hired to bring in Haitians workers. It was allegedly fortified by a well-connected network of political and business elites – mostly men – who insulated him and his business from scrutiny.

Years earlier, the Springfield Chamber of Commerce president, McDorman, shared a LinkedIn post from The Gathering’s Fall Breakfast, featuring a talk by the author of a book, “Lead…for God’s Sake.” McDorman didn’t return requests for comment.