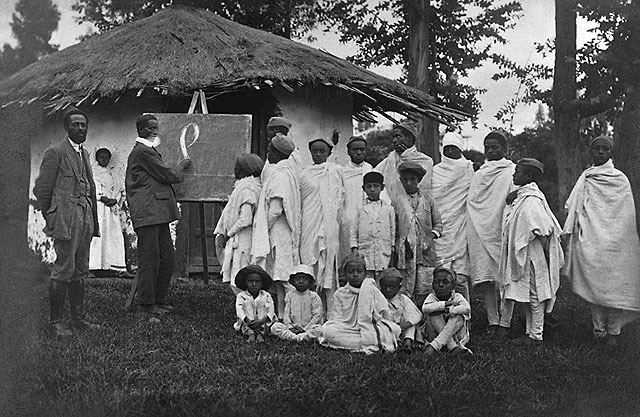

Araro’s great grandfather, Armias Asias, writing on the board during one of his classes at the first Jewish school in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

He was a prominent leader in the Ethiopian Jewish community. (Courtesy of Shalva Weil.)

Araro’s great grandfather, Armias Asias, writing on the board during one of his classes at the first Jewish school in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

He was a prominent leader in the Ethiopian Jewish community. (Courtesy of Shalva Weil.) Being Black and Jewish, I was always very aware of anti-Semitism and racism. My life will always be characterized by the separation, the hatred and “the othering” of my people.

I was born in Ethiopia. I came to Israel as an infant, but my upbringing was filled with asides about the way Jews were discriminated against in Ethiopia. My parents never said it outright; they barely spoke about their life in Ethiopia. For them, Africa was the past. Israel is the future — and a hard-fought one at that. But every now and then, if I catch them in the right mood, they will tell me about Ethiopia, the beautiful scenery, the simple lifestyle and the Jewish community.

Hiding in these happy stories were small comments about the neighbors. You wouldn’t notice them if you didn’t listen carefully. My parents said they never walked alone at night because “it was dangerous for Jews to walk by themselves,” and that they never stayed in the same place for a long time because it wasn’t legal for Jews to own land. The nickname the neighbors gave them was “Falasha,” a derogatory term which means “landless, wanderers, strangers.”

Only under pressure, after I asked several times, “How did my grandfather die?” did my mom look at me with tears streaming down her face, and say, “They murdered him. They murdered him because he was a Jew.”

My parents view these horrors as simple hate against their community. They didn’t know there was a term for that: anti-Semitism.

My family’s story defines a lot of who I am today. It is the reason why Zionism is such a big part of my identity and why I vigorously fight for the right of Israel to exist. While I was growing up in Israel, anti-Semitism wasn’t a problem but I needed to learn a new term: racism.

One of my most vivid childhood memories was when my English teacher decided to put me in a separate classroom. This classroom had fewer students who covered the material at a much slower pace. Everyone in this classroom was Ethiopian. I presumed we were put there to help us out, give us more attention and make sure we would be able to keep up with the other students. This policy was fine in principle. However, it turned out, the only characteristic that determined if you ended up in the remedial class was your ethnicity.

Growing up in Israel, anti-Semitism wasn’t a problem, but I needed to learn a new term: racism.

I wasn’t judged according to my potential, but rather by the color of my skin. And even though this decision may have come from “a good place,” it delivered the message to Ethiopian students that we were incapable of doing things by ourselves; we could not measure up to others and would always need extra help.

The @womensmarch movement didn’t stop me from supporting #feminism, the #BLM movement won’t stop me from supporting the black community in their fight for equality.

I stand behind causes & values I believe in, regardless of organizations that take ownership on them. pic.twitter.com/OkzmdHZ214— Ashager Araro (@AshagerAraro) June 9, 2020

This messaging can outlast one’s childhood and permanently taint one’s self-esteem. Thankfully, I come from a very strong family that always reassured me that I could do anything I set my mind to. While this act of discrimination didn’t permanently damage me, I’m sure it damaged others.

In my adult life, I continuously feel that people expect me to choose which group I’m going to side with: Jewish or Black people. I don’t understand that, as these are not mutually exclusive struggles. My parents lived in a majority Black country. Still, their Black skin didn’t protect them from anti-Semitic persecution. I live in a majority Jewish country, but my Jewish identity doesn’t shield me from racism. We need to fight both of those fights.

The fight against racism and anti-Semitism is ongoing; we need to fight both battles. It’s our responsibility to do so. To choose one without the other not only harms people like me but erases us from both the communities I love.

Ashager Araro is the founder of the Bettae Ethiopian Israeli Heritage Center in Tel Aviv.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.