Ever since the days of the Free Speech Movement at Berkeley in the 1960s, when college students protested the Vietnam War, fought for racial justice and camped out at the Woodstock Music Festival, the rebellious spirit on college campuses symbolized the essence of cool– the antidote to a stuffy and conservative older generation.

To a certain extent, that still holds true today. The liberal hippies from the 60s took over our major cultural pillars, and they likely still consider themselves part of the “cool club.”

Charlie Kirk, the conservative firebrand who was murdered on Wednesday while talking to college kids at Utah Valley University, wanted to change that. He took his old-school conservative message to college campuses and dared to make it cool.

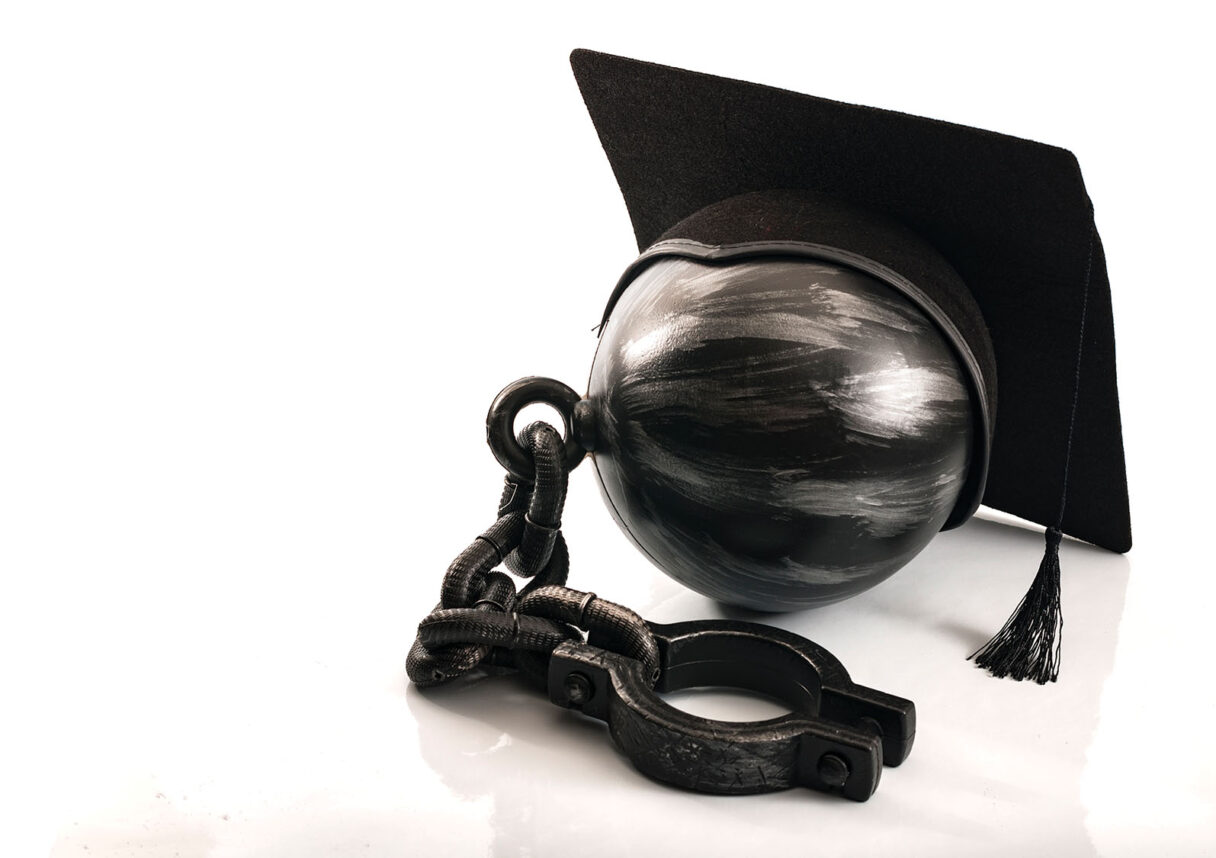

“He seemed like a guy who would be popular on campus, who would be invited to the good parties, who would have friends outside of political activism, who wouldn’t just show up in a bow tie plotting how to take over the Young Republicans,” Ross Douthat writes in The New York Times. “The fact that he was himself a college dropout, leaving college early to found Turning Point USA, was almost the perfect touch: There is nothing more normally American than choosing a really good entrepreneurial opportunity over the full undergraduate four years.”

Kirk, at only 31, became so successful and influential within the conservative world he could have received a high-level position in the Trump administration. But he aimed higher.

“We want to transform the culture,” he said in an interview in February.

Transform from what to what?

“Conservatism on college campuses has traditionally mixed tweedy intellectualism, shock-value provocation and ruthless training for future G.O.P. operatives,” writes Douthat. “All of these forms… have tended to attract nerds and dorks and oddballs, campus outsiders, the inherently uncool.”

Kirk may have had conservative views, but he was far from uncool. As Douthat writes, he “built his career and reputation organizing a different kind of campus conservatism — fun-loving, masculine, rowdy, mainstream, even faintly cool.”

We rarely talk about the cool factor when discussing the politics of power. It feels nebulous. It’s hard to measure. It doesn’t fit the talking points of policies and ideologies.

Indeed, it transcends all of that.

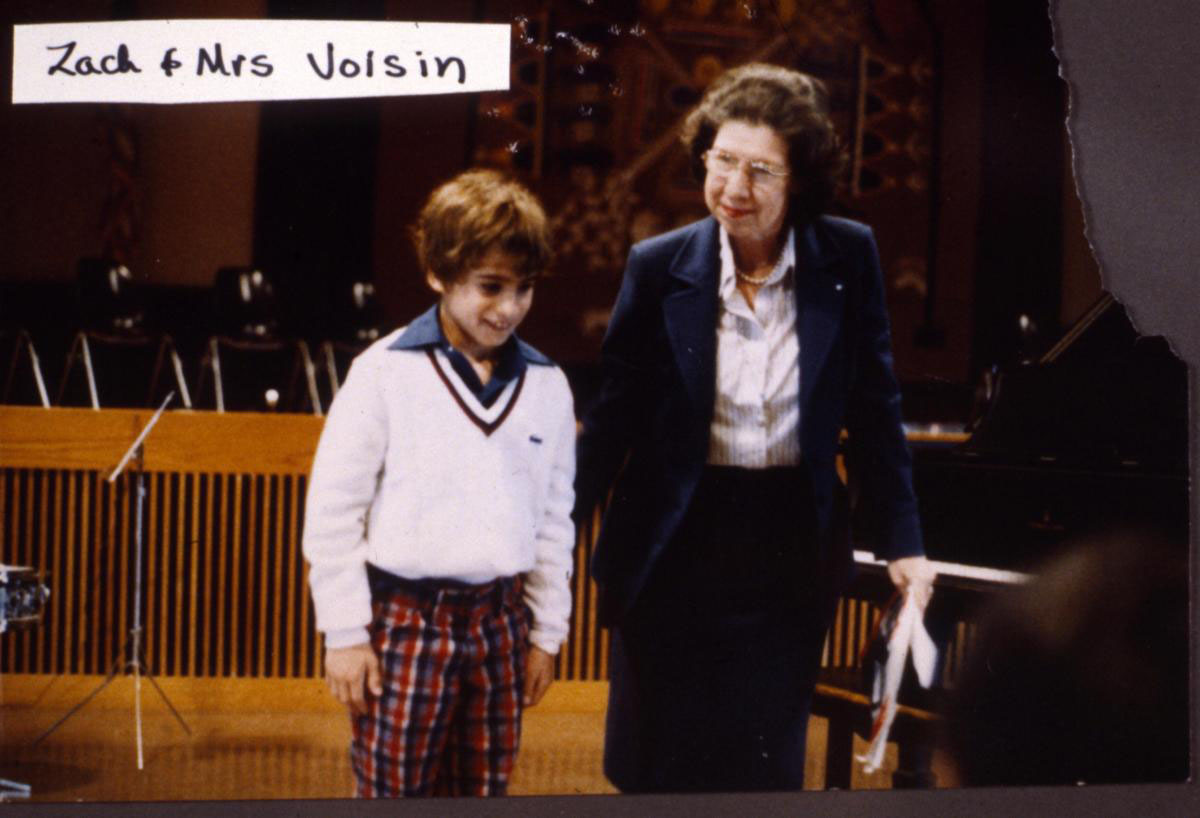

Cool is that intangible trait we internalized during our most formative years in high school. I have distinct memories of the cool kids in my high school in Montreal. I remember their names. I remember their swagger. Some were athletes, some were musicians, some were rebels, and others were just cool-looking.

President Barack Obama was the essence of cool. He had the whole package—the look, the ideas, the delivery. He was against the Iraq War, he could speak to any audience, and he never lost his cool.

The Democratic party, almost by default, became the natural home of the cool people since those days in the 60s when the nation was listening to anthems like Crosby, Stills and Nash’s “Four Dead in Ohio,” about the police killing of college students at Kent State.

The Democratic hold on cool began to loosen with the arrival of the woke movement, which featured a growing intolerance for anything that might hurt people’s feelings, otherwise known as “microaggressions.” Although this was rooted in compassion and empathy, it undermined the cool factor. How cool can a fragile scold be?

Charlie Kirk saw an opening and barged right through.

He engaged with tens of thousands of college students in hundreds of campuses over more than a decade and stood tall with his coolness and his arguments. He wanted to make loving America cool again.

“He was a harbinger and then an embodiment of Trump-era populism,” Douthat writes, adding that he “became a spokesman for a youthful right that seemed both more rebellious and more relaxed (like a good college hangout) as progressivism became more institutionally dominant and uptight.”

The shift of cool away from Democrats was most evident in the 2024 elections, when the party of Hollywood and rebellious college students became the party of the elite and the uptight. If you want to win a national election today, you’re much better off with Joe Rogan than with George Clooney or the billionaire Oprah.

Why did Kirk become so threatening that someone felt compelled to assassinate him? I’m no psychologist, but it could well be that Kirk’s very coolness, his ability to express controversial views in disarming ways, was seen as the ultimate threat precisely because it helped him reach new people.

Of course, conservatives have a long way to go before they can hope to grab the cool mantle, especially with the loss of their campus hero. Maybe, in our fragmented and frenetic social media ecosystem, no party can grab it.

But Charlie Kirk, by being earnest rather than smug, polite rather than condescending, and cool in an old-school kind of way, has made the elusive cool label up for grabs, or at least broadened its definition.

In doing so, Kirk also managed to gain the respect of icons of the left like Cenk Uygur, who posted on X yesterday, “Charlie and I disagreed a lot about really important things. But somehow, we didn’t lose our humanity. We were still fellow Americans.”

Not losing our humanity may be the coolest thing I can think of.

What a singular tragedy, for us and for his family, that Kirk was stopped from continuing that mission.