As Jesse Eisenberg sat down at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts to talk about his play, “The Revisionist,” the actor and playwright noticed that members of a camera crew from a previous interview were struggling to rearrange the furniture in the room. “Can I help?” Eisenberg asked, immediately jumping up to assist in shlepping the heavy tables and chairs.

When Eisenberg returned, he was warm, cerebral and at times self-effacing, in particular about what he perceives as his own quirks and foibles. The 32-year-old actor, who earned an Oscar nomination for his portrayal of Facebook mogul Mark Zuckerberg in “The Social Network,” said he never watches his own movies — even the upcoming “Batman vs. Superman: Dawn of Justice,” in which he stars as the arch-villain Lex Luthor, “because I’m just very self critical.” He said he often feels like he’ll never get another movie role or write another play.

When he’s standing next to his “Batman vs. Superman” co-star, the Israeli actress Gal Gadot, he added, “The only thing I can’t believe when I crane my head up to make eye contact is that we’re from the same gene pool.” And Eisenberg doesn’t read reviews of his own work because “even if they say this is the greatest thing on Earth, I’m like, ‘What about the other planets?’ ”

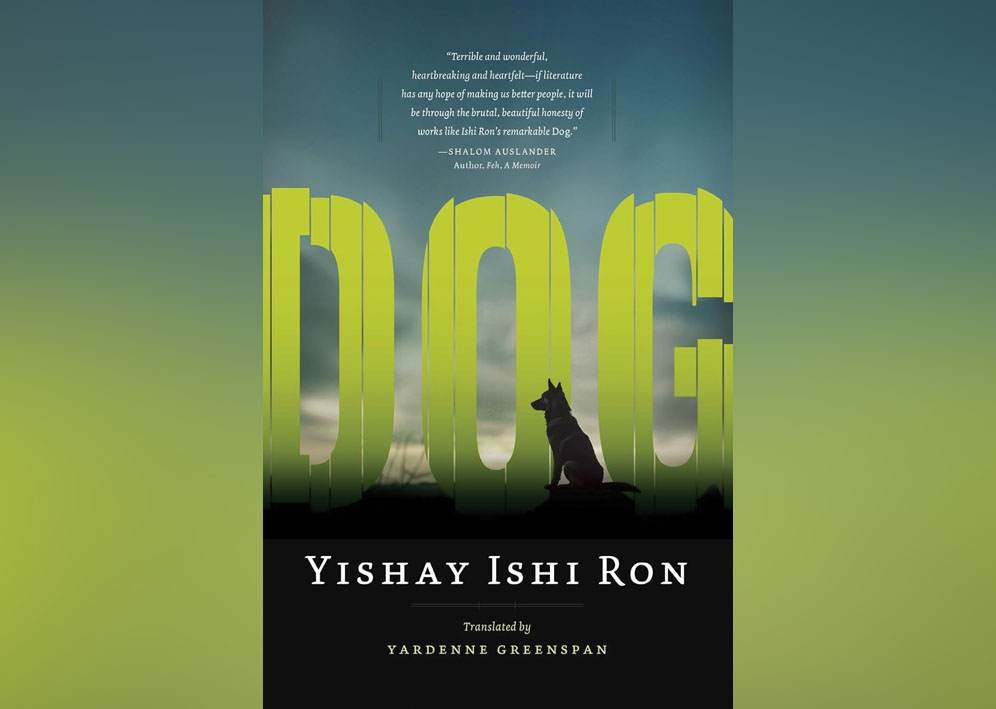

“The Revisionist,” the first play written by Eisenberg, who also contributes regularly to The New Yorker, tells the story of David, a callous 20-something Jew from Manhattan who visits an elderly cousin in Poland seeking a quiet place to revise his ill-received science fiction novel. His cousin, Maria, lives alone in a tiny apartment whose walls are covered with photographs of her American relatives, whereas David rarely sees his own New York family. While in Poland, however, he learns how Maria survived the Holocaust by passing as a Catholic girl, and he leaves her home a somewhat changed man.

“The Revisionist” premiered off-Broadway in 2013, and starred Vanessa Redgrave as Maria and Eisenberg (“Adventureland,” “Zombieland,” “The End of the Tour”) as David. The play will open with a new cast (that doesn’t include Eisenberg) this week in Los Angeles.

“David is feeling a kind of quarter-life existential crisis,” Eisenberg, who lives in New York, said of the character, who in a way is his alter ego. “He has an unconscious need to have some kind of grounding in his life and to learn what it truly means to suffer. He’s part of a generation of American white men who have a lot of convenience but a lack of meaning, and if we’re interested, we search for that meaning through people whose lives have been more difficult than ours.”

When Eisenberg began writing the play about nine years ago, he, too, was “also feeling a bit of an existential crisis,” he said. “I had just started becoming someone in the public eye, and I was getting scrutinized in a way that made me feel self-conscious and embarrassed as well as curious about myself. I was eager to have something to hold onto besides being a movie actor, and exploring my heritage gave me a feeling of grounding that I was missing.”

Eisenberg’s journey to write “The Revisionist” actually began with his own great-aunt Doris, now 104, a Polish-Jewish immigrant who lives in New York whom he has visited every week since he was 17. “In a strange way, the inspiration was this kind of oddly contentious and ultimately fraught relationship between a young man and an older woman,” he said. “At her worst, Doris is passive aggressive, and at best she’s a great heroic inspiration. And at my worst, I’m probably catty, narcissistic, self-involved and bratty, [while] at my best I’m a kind of dutiful student of her teaching. I would say that if she weren’t such a good person, she’d be a cult leader. She has a strangely positive and militant life philosophy.”

Before Eisenberg set off to shoot the film “The Hunting Party” in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2006, he mentioned to Doris that he would like to visit her hometown village of Krasnystaw after production wrapped. “She seemed uninterested,” he recalled. “But I wanted to explore my family’s heritage, probably as an extension of my own narcissism.”

Before Eisenberg traveled to Doris’ former home in Krasnystaw, he drove across Poland to visit her first cousin, Maria, who lived alone in a tiny, decrepit apartment in the rural village of Szczecin. After camping out with her for a week, he recalled, she “guilted” him into staying longer. “She said something along the lines of, ‘Thank you for coming; I know I’ll never see you again,’ and it was heartbreaking,”Eisenberg said. “This was a woman who had had so much loss in her life that even the comparatively small gesture of me leaving was painful.”

And so, after going off to visit Doris’ hometown, the actor returned to stay with Maria for two more weeks, during which time he learned details about Maria’s devastating experiences during the Holocaust — including witnessing a Nazi kill her brother by shooting him in the face. “I would kind of pry into the more salacious elements of her story, because as an American who had read ‘Night’ and watched ‘Schindler’s List,’ that was the stuff that jumped out at me,” he admitted. “When I was with Maria, I still had those desires to learn about the more shocking, dramatic parts of her horrific story, but that wasn’t the appropriate thing to do.”

The play’s David, as well, “has what I would say is an unethical interest in exclusively the salacious parts of his cousin’s story,” Eisenberg said. “Like many American Jews of his generation, this comes from being removed enough to not have to worry or think about [the Holocaust], but connected enough to feel the confidence in prying. That’s a dangerous combination I know I personally have experienced, and it’s something I’m ashamed of.”

And yet, after hearing his cousin’s story, Eisenberg also came to question his own emotions: “How can I have so many sad feelings about things that are petty, like what movie roles I get, when there is real suffering in the world?”

The actor decided to turn the experience into a play, in part, because he was feeling pigeonholed as an actor. While “The Hunting Party” was a good movie, he said, “I felt like I was almost portraying a kind of Jewish stereotype — the smart but frantic, nervous person who is sheepish. I did not want to continue doing that. I’m an ambitious person, so I felt I had something to prove and I wanted to do something that was different than acting as a nervous sidekick in a movie.”

When “The Revisionist” was performed in Israel during the Gaza conflict in 2014, Eisenberg said he traveled to see the performance and to tour the Jewish state, even though he often had to scuttle into bomb shelters; once, while driving on a highway, he said, he “saw bombs explode over my head from the Iron Dome.”

These days, Eisenberg’s career has evolved far beyond his previous typecasting, especially with his performance as Lex Luthor. “He’s probably the most exciting role I’ll ever get to play in my life,” Eisenberg said. “The screenwriter, Chris Terrio, was able to infuse the character with a modern psychology that we would recognize in dangerous people today; [Luthor] is absolutely not a campy, one-note villain. I would say he’s either a sociopath or an incredibly emotional person, but never on behalf of anybody else.”

For Eisenberg, taunting the characters of Batman and Superman was a blast. “I’m yelling and torturing these two Adonises, played by Ben Affleck and Henry Cavill, so I had license to hit them and tease them and make fun of them — all under the safe umbrella of the movie,” he said.

“The Revisionist” starts previews on March 29 and opens April 1 at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills, where it will run through April 17. For information, visit thewallis.org. “Batman vs. Superman” opens in theaters March 25.