PowerSiege/Getty Images

PowerSiege/Getty Images Let’s drop politics for one week. Let’s talk about something that isn’t politics. Well – it is about politics, and it isn’t. A new finding marks a significant, lasting change, which could have many consequences. It marks the distancing of a large public from everything that smells of “Judaism” and from everything that might imply a Jewish connection. That’s a social trend that has more than one political meaning.

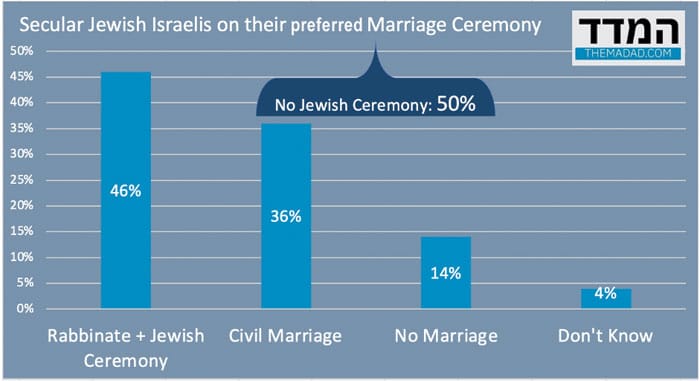

The data (from a survey by themadad.com) provides the starting point: we asked what Israeli secularists would do if they were given the legal option to marry as they see fit. And note that the wording is important: We asked about a hypothetical situation — “what would you do in case of” — which is currently not in sight. The current government is unlikely to be the government that legalizes civil marriages in Israel. On the other hand, the question of what people would do if there were a certain possibility still teaches us a lot about their state of mind.

Look at the graph below in “A Week’s Numbers.” About 40% of Israeli Jews self-define as secular. What do these secularists tell us? Two things. First, they don’t like the rabbinate. Only a few of them (12%) would like to have a marriage certified by the Rabbinate. A reminder: In Israel today, that’s the only marriage that counts as legal. Thirty-four percent of seculars would still like to have a Jewish wedding, but not one that’s connected to the Rabbinate. And so, the combined share of secular Israelis who’d choose a Jewish wedding, Rabbinate or not, is less than 50%. In other words, more than half of the seculars in Israel would not choose a Jewish wedding.

That’s a big deal. But why do seculars not want a Jewish wedding? Good question. Maybe because they understand a “Jewish” wedding as a wedding that has a rabbinical connection, and they don’t like rabbinical connections. Maybe because the very context of Jewishness is no longer something they feel comfortable with, for a political, or social, or cultural reason. Either way, this is a significant finding. I’d say a troubling finding. A Jewish wedding is an easy way for anyone to celebrate an identity, a culture, an affinity to a certain tradition. A Jewish wedding ought to be something that we all want — an uncontroversial and happy celebration that mixes the personal and the communal.

Of course, the conclusions you draw from such finding will not necessarily be the same.

Some will say: that’s a disaster — and so we need to tighten the supervision in such a way that will make it even more difficult for Israelis to have a marriage uncertified by the rabbinate. These Israelis (and I suspect that some government ministers might have this view) would call for enhancement of the power of the religious establishment to handle all marriages.

Others will say: that’s a disaster — and what we need is the exact opposite. Look, they’ll say, at the damage the religious establishment had wrought. Because of its dogmatic approach, Jews not only stay away from rabbis, but they also stay away from Judaism itself. They do not even want a Jewish wedding!

Still others will say: What’s the problem? A wedding is a personal matter, and it’s none of anyone’s business what kind of wedding individual Israelis want.

Still others will say: This means a future of division of the people of Israel. Soon there will be no possibility of marriages between religious and non-religious Israelis.

Still others will say: We must start a vigorous campaign to encourage rabbinate licensed weddings.

Still others will say: you got it backwards — what we must have is a vigorous campaign to encourage Jewish weddings (but not necessarily rabbinate licensed) and strengthen Jewish identity and Jewish pride.

The challenge is that we have a free society that strives to encourage and bolster a Jewish culture, in which a large population often feels distanced from that very culture.

In short, the data is just data. The conclusions combine the data with more than a grain of ideology. The data does not solve the dilemma, or the debate or the challenge. It is merely a helpful tool for those who want to better manage this debate, and deal with the challenge. What exactly is the challenge? This too can be debated, but here’s one way to succinctly describe it: the challenge is that we have a free society that strives to encourage and bolster a Jewish culture, in which a large population often feels distanced from that very culture. It’s a social challenge, it’s an identity challenge, it’s an ideological challenge. We are far from seriously dealing with it.

Something I wrote in Hebrew

Here’s what I wrote when Israel’s court made the controversial decision that Shas leader Aryeh Deri could not serve as a minister (because of tax evasion indictment).

Former PM Olmert did not think he was guilty when he entered the prison. Former President Katsav did not think he was guilty when he entered the prison. Former PM Rabin did not want to fire Deri when he was forced by the court to do it. Now, Netanyahu doesn’t want to do it either. And of course, Deri himself does not think there is any reason to prevent him from becoming a minister and many of his constituents, perhaps all, agree with him … None of this is important. The court decided, and its decision will be enforced, because otherwise, the State of Israel ceases to be a state of laws and becomes a state of anarchy, and all that is left for the citizens to do is to arm themselves – because that is what people do when there’s anarchy.

A week’s numbers

This is the graph I explain above.

A reader’s response:

Elan Azulai asked: “Is what we see today the worst political atmosphere in Israel’s history?” Answer: you mean, more than the Rabin assassination (1996)? More than Begin’s threat to storm the Knesset (1952)? More than the murder of Emil Grünzweig in a demonstration against the Lebanon War (1983)? Maybe, but it’s surely not a clear-cut case.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.