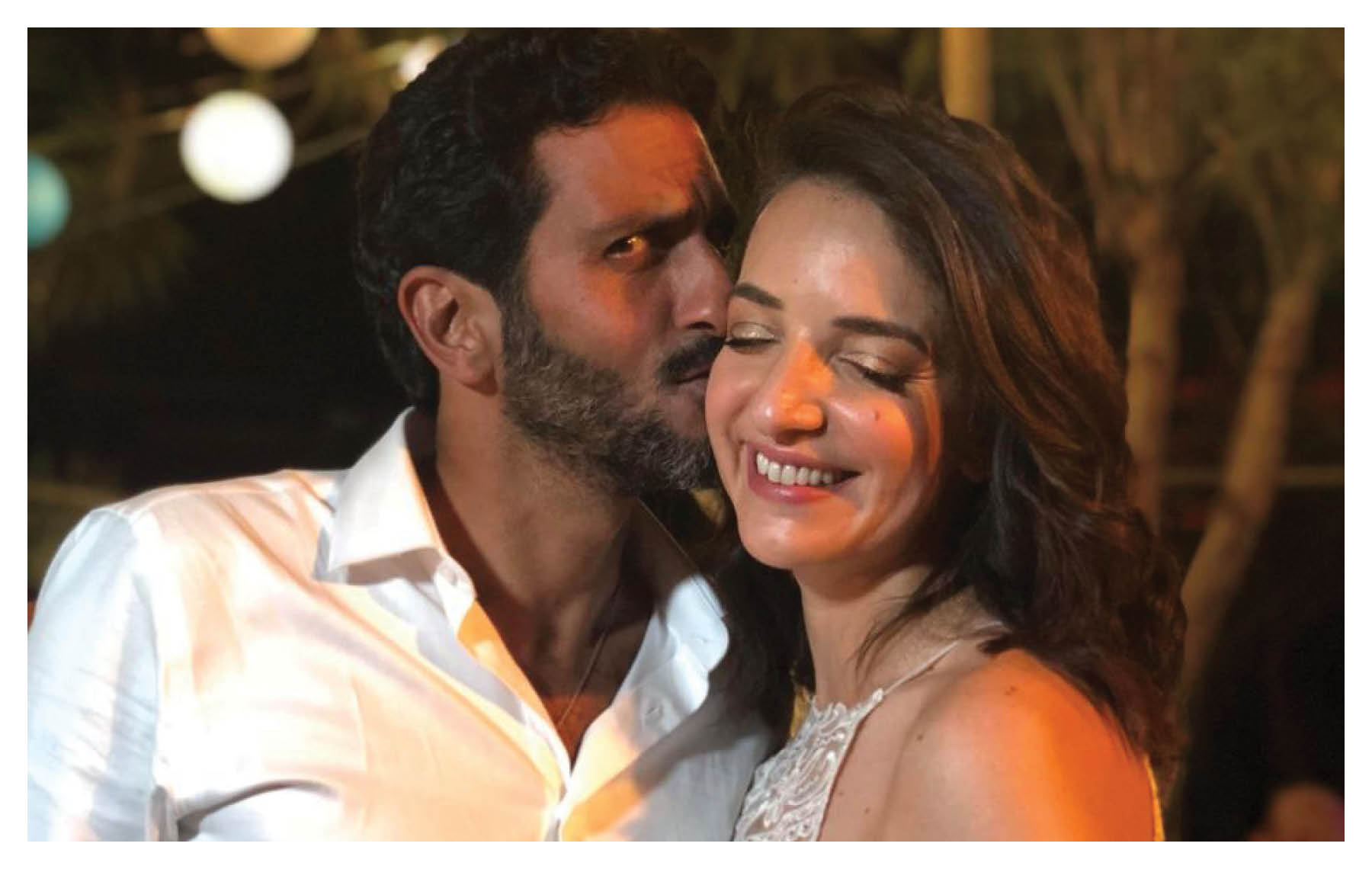

Lucy Aharish and Tzachi Halevi pose for a photo at their wedding party in Hadera, Israel, on Oct. 11.

Photo by Meggie Vilensky/Reuters

Lucy Aharish and Tzachi Halevi pose for a photo at their wedding party in Hadera, Israel, on Oct. 11.

Photo by Meggie Vilensky/Reuters Two Israelis get married. An everyday occurrence but in this case, both Israelis are celebrities; one a TV journalist and personality, the other, an actor. So the wedding is national news. Also, one, Lucy Aharish, is a Muslim — the other, Tzachi Halevi of TV’s “Fauda” fame, is Jewish.

Intermarriage in Israel: The fewer you have them, the more noise you have. A Jew and a Muslim cannot legally marry each other in Israel. But Israelis long ago found ways to circumvent laws they dislike, especially laws that attempt to impose rabbinic dictates on them. A Jew and a Muslim rarely marry each other in Israel.

After the celebrated wedding, a Member of Knesset from the Likud Party released an ugly comment, denigrating the couple. A pushback was quick and harsh. Aharish is a charming and beloved public figure. She is sharp-tongued, patriotic, pretty and honest. It is easy to understand how an Israeli-Jewish actor fell in love with her. Still, a debate ensued about the issue of intermarriage, revealing a wide array of views. And at the heart of this issue, a paradox.

Here is it:

The sector that most opposes intermarriage — the religious right — is also the sector that most opposes separation from the Palestinians in the West Bank. In fact, the sector opposes intermarriage but also opposes creating the conditions that reduce the incidence of intermarriage.

On the other end of the political spectrum, the people least concerned about intermarriage are those most inclined to separate from the Palestinians, hence reducing the interaction of Jews and non-Jews between the Jordan Valley and the Mediterranean.

Interesting, isn’t it? If you are concerned about intermarriage — or better understand that although marriage is a complicated, personal decision, but that for Jews, a high number of intermarriages is a problem — wouldn’t you strive to have a clear Jewish majority in a well-defined territory? The inconsistency of the religious-right position is noteworthy. And even more noteworthy is the reason for it.

In fact, there are two reasons. The first is that the religious right doesn’t understand the society in which they live. The second is that objection to “intermarriage” in Israel is more about nationality than it is about religion.

“Objection to ‘intermarriage’ in Israel is more about nationality than it is about religion.“

Beginning with the first undercurrent that creates the paradox, members of the religious right do not understand that for many centrist, leftist and mostly secular Israelis, intermarriage is hardly a demon. Consider this: Self-defined “totally secular” Jewish Israelis prefer that their relative will marry a non-Jew over him or her marrying a Charedi Jew.

Consider this: A clear majority of Israelis support the idea of establishing civil marriage in Israel knowing full well (at least, most know) that this creates a legal path to intermarriage. In other words, one of the reasons why the religious right doesn’t see the contradiction between greater Israel and objection to intermarriage is its assumption that most Israelis will behave like a member of the religious right, that is, refrain from intermarriage even in a highly diverse society. This is a false assumption. Jewish Israelis, given the opportunity, will intermarry in high numbers.

The second undercurrent makes the religious right’s assumption seem somewhat more rational. Consider this: According to a recent survey by Jewish People Policy Institute, Jews in Israel have a much higher objection to a “close relative” marrying an Arab than to a “close relative” marrying a non-Jew that is not Arab. The difference is stark — not merely a few percentage points. The percentage of Jewish Israelis who would be “shocked” if a relative married an Arab is double the percentage of Israeli Jews who would be “shocked” if their relative marries a non-Arab gentile. In other words, objection to intermarriage — common among most sectors of Jewish Israelis — is much more about national identity that it is about religious norms.

With these numbers in mind, the religious right’s position seems less contradictory. It is not worried about intermarriage in a greater Israel — in which many Muslim Palestinians reside — because it knows that Jewish Israelis object to marriage with Arabs, not for religious reasons, but for national reasons. Alas, such objection depends on specific circumstances. It depends on circumstances of ongoing national conflict. In other words: for the religious-right position to have merit, the conflict with the Palestinians must never be resolved.

Or else.

Intermarriage in inevitable. Some leftist-secular Israelis might not care to have such an outcome, but religious-right Israelis do care. Hence, an unresolved paradox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.