He’s the Passover Haggadah’s second-favorite villain. Millennia before Harvey Keitel’s Mr. White captured the attention of audiences in Quentin Tarantino’s 1992 classic, “Reservoir Dogs,” the Bible’s own Laban (Hebrew for white) was antagonizing the Children of Israel’s eponymous ancestor.

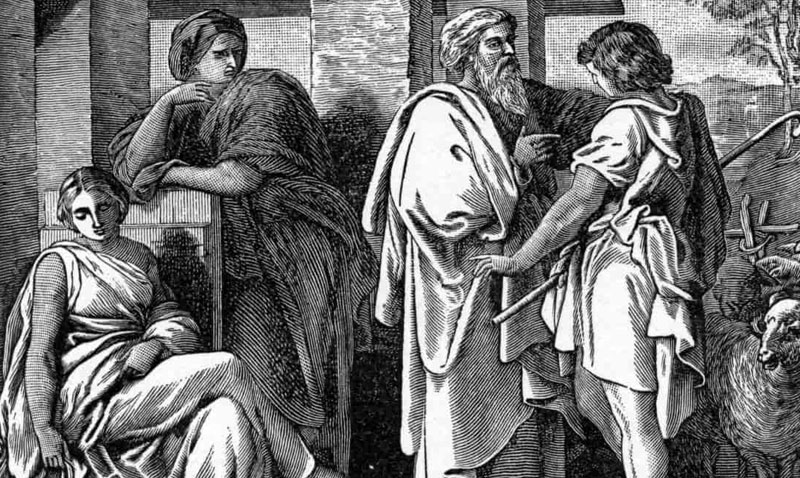

For those in need of a brief refresher, Laban was the uncle of Jacob, also known as Israel. He appears for the first time in this week’s parsha, Chayei Sarah, as a young man standing in the way of his sister marrying Isaac. The Good Book then spends many chapters documenting Laban’s dastardly deceptions. He tricks Jacob into marrying Laban’s daughter Leah in lieu of Jacob’s chosen bride Rachel, cheats his son-in-law out of his rightfully-earned wages, and seeks to stop him from returning to Canaan, Jacob’s family’s rightful homeland.

So sinful was Laban that every Festival of Freedom he’s the warm-up act for Pharaoh, the evening’s main malefactor. “An Aramean [Laban] tried to destroy my father,” we read towards the beginning of the Haggadah, “…and he went down to Egypt.”

Perhaps, as Passover’s classic text posits, Laban was actually worse than the merciless monarch – while Egypt’s tyrant enslaved only the male Israelites, Laban had tried to destroy the entire family of Israel. No wonder Laban sits alongside Mr. Red, Esau the Edomite (adom is red in Hebrew) in the rogues gallery of ancient Jewish nemeses.

While the Bible offers no origin story nor tells of Laban’s subsequent adventures after he and Jacob build a monument to their negotiated détente, rabbinic tradition fills in the blanks.

The Midrash HaGadol has Laban’s birth aligned with those he would soon oppress. “Laban was born through the merit of the Patriarch Abraham,” it teaches. When Sara, Abraham’s wife, had her barrenness miraculously healed by God, Laban’s maternal grandmother was similarly gifted a pregnancy.

How was it that Rachel and Leah grew up to be righteous matriarchs despite their dad? Clearly because of their mother, says Sefer HaYashar. Named Adina, “delicate,” her kindness and compassion counteracted Laban’s nefarious plotting.

Not only was the man whose name means “colorless” a black-hearted financial swindler, Laban was also an expert in sorcery, adds the Zohar. When Jacob escaped Laban’s clutches, “Laban did not pursue Jacob to fight [physically] with him, for Jacob’s camp was stronger than his. Rather, [Laban] wished to kill [Jacob] with his mouth and to make him perish from the world.”

Even Laban’s hometown reflects his diabolical nature – “Aram” comes from the same root used in Genesis’ third chapter to describe the Garden of Eden’s conniving snake.

The 13th-century Spanish kabbalist Rabbi Joseph Chiquitilla noted that Laban’s slick-tongued scamming might relate to the biblical affliction of tzaraat, that skin disease traditionally viewed as a result of sinful speech. After all, its trademark is white splotches appearing on skin.

It’s no surprise then that other sources spot in Laban a foreshadowing of another sorcerer who sought to destroy the Jewish people through evil speech, Balaam. That donkey-riding prophet hired by King Balak of Moab to curse the Israelites in the Book of Numbers was the Joker to Moses’ Batman, as Laban was to Jacob. In fact, the Talmud in Tractate Sanhedrin says Laban was Balaam’s father, now referred to as Beor. Targum Yonatan took things one step further, suggesting Balaam himself was actually Laban – having lived for hundreds of years – in disguise. Laban was now operating under a new name because it was he who sought to swallow up, balah, the people, am, of the House of Israel. And what about that wall built as a monument to Jacob and Laban having finally put aside their differences? It’s the same one Balaam’s donkey smashes up against in an effort to dissuade Balaam from his determination to destroy Jacob’s descendants.

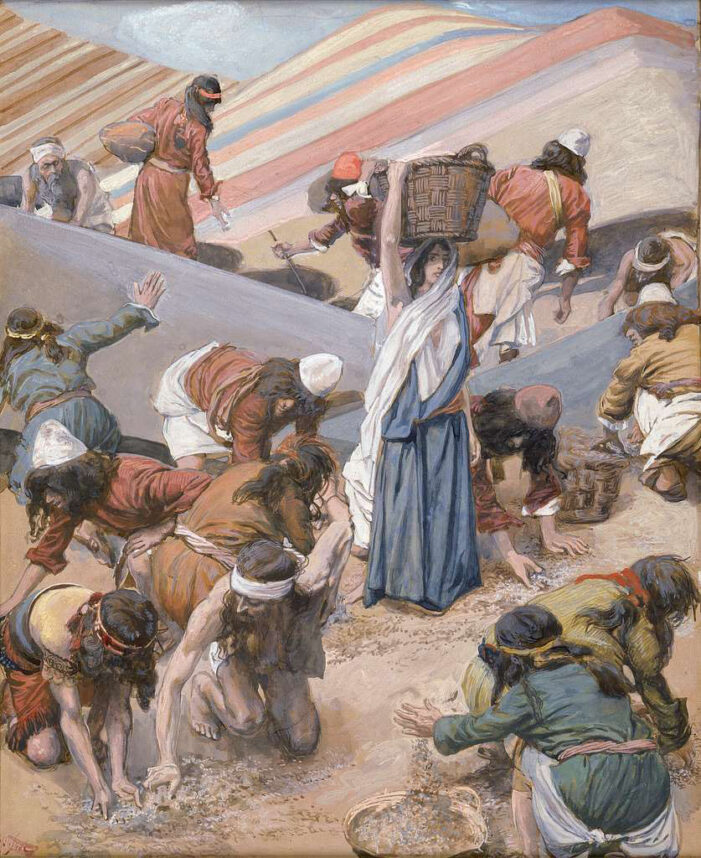

Before Balaam/Laban met his end in battle with the Israelites as they neared entry into the Promised Land, the sorcerer, compelled by God, expressed admiration for the descendants of their father figure whose covenantal aspirations he had sought to deny, as Numbers’ 23rd and 24th chapters detail: “No misfortune is in [God’s] plan for Jacob; no trouble is in store for Israel. For the Lord their God is with them.. These people rise up like a lioness… Blessed is everyone who blesses you, O Israel, and cursed is everyone who curses you.”

Laban, after all his colorful deceptions and divinations had failed, learned the lesson Israel’s contemporary foes would be wise to heed. While every epoch has offered its spectrum of enemies, they have all ended up on the losing side. Yet the Nation of Israel still lives.

Laban, after all his colorful deceptions and divinations had failed, learned the lesson Israel’s contemporary foes would be wise to heed. While every epoch has offered its spectrum of enemies, they have all ended up on the losing side. Yet the Nation of Israel still lives.

Rabbi Dr. Stuart Halpern is Senior Adviser to the Provost of Yeshiva University and Deputy Director of Y.U.’s Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought. His books include “The Promise of Liberty: A Passover Haggada,” which examines the Exodus story’s impact on the United States, “Esther in America,” “Gleanings: Reflections on Ruth” and “Proclaim Liberty Throughout the Land: The Hebrew Bible in the United States.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.