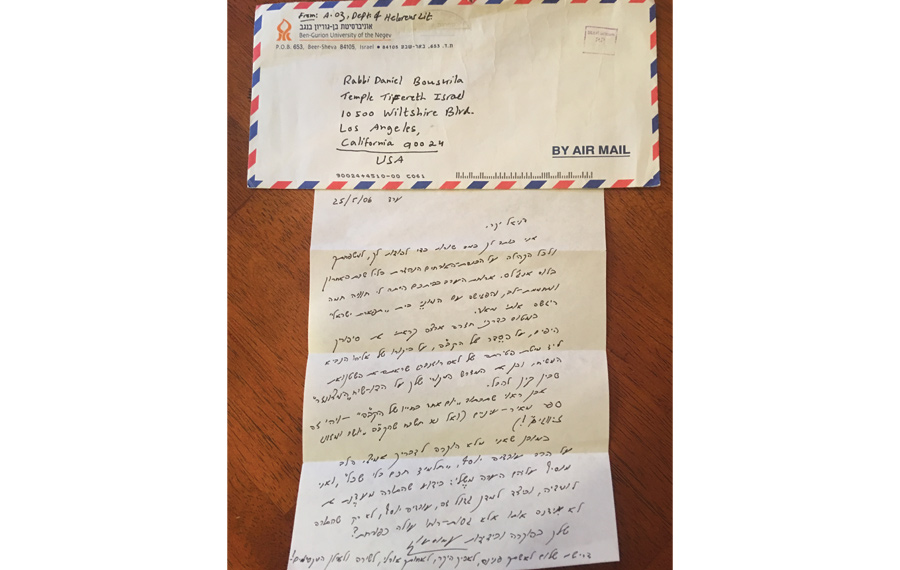

A letter that Rabbi Daniel Bouskila received from Amos Oz

A letter that Rabbi Daniel Bouskila received from Amos Oz Editor’s Note: Israeli writer, novelist, journalist and intellectual Amos Oz died Dec. 28 in Tel Aviv. He was 79.

Dear Amos,

I’m sitting at my desk, painfully contemplating your untimely passing and trying to figure out how to express myself during this difficult moment. I want to write an article about you, but that’s so abstract and impersonal. Rather than writing the standard tribute, I decided to write this letter, from one friend to another. After all, it was through our letters — handwritten on small pieces of nondescript paper and airmailed in envelopes lined with red, white and blue — that you and I communicated for so many years. In those letters — written in your beautiful Hebrew handwriting with the crooked paragraphs that never properly aligned with the page’s margins — we exchanged ideas on Hebrew literature, the theology of Agnon and life in general. We freely expressed ourselves, explored new ideas and deepened our friendship.

It’s not surprising that letter writing was such a powerful medium of communication for you. You elevated letter writing to an art form in your novel “Black Box,” whose diverse characters interact by writing letters to one another. You ingeniously showed us through the seemingly simple act of writing letters that one can construct an intriguing plot, develop characters in depth and transform mundane details of life into meaningful expressions of innermost emotions.

You taught me how to appreciate those tiny details within a half-hour of when we first met. I had picked you up at Los Angeles International Airport on a Friday afternoon, and within a few minutes we were talking about what became our shared passion — the literature and persona of S.Y. Agnon. I was so engrossed in our discussion that I did not notice I had exceeded the speed limit. But a traffic cop noticed. There I was, with my literary role model in my car in our first-ever meeting, pulled over for a speeding ticket!

Once we parted ways with the friendly traffic officer, you remarkably put me at ease by saying, “I wonder if anybody actually reads all of the small, printed details on these traffic citations?” I looked over at you, wondering where you were going with this. “After all,” you continued in your poetic Hebrew, “somebody somewhere took the time and effort to painstakingly write this text. Somebody should honor that person by at least reading what they had to say.” Only you, Amos, a kind soul who reveled in the small, printed details of life, could remind me that behind the text of a speeding ticket is a person who took the time to compose it. Only you, Amos, a brilliant master of transforming mundane situations into exciting events, could elevate the annoyance of a speeding ticket into a potentially meaningful literary moment.

Your treatment of my speeding ticket reminds me of what you did in your masterful memoir “A Tale of Love and Darkness,” when you described with such loving detail the buildup toward the one phone call your family made every two to three months from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv. With charm, wit and humor, you said, “I don’t remember whether we put on our best clothes for the expedition to the pharmacy, for the phone call to Tel Aviv, but it wouldn’t surprise me if we did. It was a solemn undertaking.”

Your sensitivity toward the author behind the speeding-ticket text reminds me of another story you tell in “A Tale of Love and Darkness,” about the moral dilemma over selecting which cheese to buy at Mr. Auster’s grocery shop, the kibbutz cheese made by the Jewish cooperative Tnuva or the Arab cheese produced in the nearby village. Like the speeding ticket, behind each block of cheese stood people who produced it, and your dilemma expressed a personal sensitivity toward each of them.

That’s what made you such a great author, my dear friend, your sensitivity toward people and your deep interest in their personal lives and feelings. You were a great author, not only because of your literary talents and creative genius, but because you spent a lot of time listening to others.

I experienced your gift as a listener at my own Shabbat dinner table, when I saw how you interacted with my family, especially my children. You told my then 10-year-old daughter, Shira, that you wrote stories for a living, and you asked her if she had any good stories to tell. “I just wrote a short story,” she said. “Well, Shira,” you replied, “I would love to hear it.”

Shira brought the story to the table, and for the next eight minutes we all listened to her choppy first attempt at narrative fiction. You sat there patiently, with your eyes closed, attentive to every single word. As she finished reading the story — which included a character named Victoria who had discovered a dead body — your reaction was not a standard “Good job; I really enjoyed it. Keep writing, kid.” Instead, you looked at Shira and treated her as your peer. “Shira,” you said, “from the time Victoria discovered the dead body until she reported it to the police, I would have wanted to know a bit more about how she reacted and what she felt. Did she cry? Was she afraid? Did she tremble? I think you need to fill those gaps so we get to know Victoria more personally.” How amazing that you, an internationally famous author, paid such a huge compliment to my little daughter by taking her seriously, listening to the details of her story and critiquing it with constructive suggestions.

“You were a voice of social justice, and you taught us what it means to use words in a constructive fashion to combat racism, xenophobia, extremism and zealotry.”

In the same way you listened to Shira with care and respect, you listened to the voices of so many others. You were the master of penetrating the minds and souls of the “Israeli next door.” You invited us into their little shops, their kibbutz fields, their living rooms, their bedrooms and their hearts. In your novels, we never read sweeping epics romanticizing Israel on a grand scale. Instead, you chose to explore for us the internal struggles, triumphs, fears, romances, aspirations and disappointments of the average Israeli.

In your dark novel “My Michael,” you took us on a painful journey through Hannah Gonen’s loneliness and depression. Many years later, we learned that Hannah’s struggle was a lens into your beloved mother’s bouts with depression. The very titles of some of your novels, short-story anthologies and collections of essays — “Between Friends,” “Scenes from a Village Life” and “Here and There in the Land of Israel” — speak to the personal dimension of Israeli life that you opened up for us. As such, you were the poet of Israel’s inner soul. Through your pen and pencil (I know you wrote with both!), you gave voice to the people of Israel, one person at a time.

I admire you for your courage and strength to always speak your mind, especially when it went against the flow. You respected everyone but feared no one. You were a voice of social justice, and you taught us what it means to use words in a constructive fashion to combat racism, xenophobia, extremism and zealotry. While the common talk in Israel is often about the next war, you dared us to think differently and envision peace. In that sense, my friend, you were a modern-day prophet, making your death that much more painful for all of us.

I know you did not define yourself as a religious person, but as I once told you during a deep discussion about Agnon we had in a Palo Alto hotel lobby, if the definition of “religious” can include those who challenge and question God, then you, Amos — like Agnon — had a deeply religious soul.

As I write this final letter to you, I do so with the painful awareness that, this time, I don’t expect a response. I don’t know how much postage it would take for this to reach heaven, but I do know that if there is a heaven, you are certainly there. If heaven exists, then you most definitely are in its literary salon, already engaged in deep conversations with Tolstoy, Chekhov, Brenner and Agnon, your literary peers.

The world has lost a literary giant, and Israel has lost her voice of conscience. As for me, I have lost a dear personal friend.

With eternal love and admiration,

Daniel

Rabbi Daniel Bouskila is the director of the Sephardic Educational Center and the rabbi of the Westwood Village Synagogue.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.