On June 9, 2009 Javier Sinay, a Jewish Argentine journalist, received a startling email from his father, who had just discovered that his grandfather — Sinay’s great-grandfather — had written an account of gruesome crimes against Jews.

In an article published in Yiddish in 1947, Mijl Hacohen Sinay, Sinay’s great-grandfather, wrote that between 1889 and 1906, twenty-two Jews were murdered in an Argentine area that had been heavily colonized by thousands of Jews who had immigrated from Czarist Russia in the late 1800s.

The murders, described in gory detail, were the stuff of nightmares. One involved the deaths of three members of one family; another, the dismemberment of a young woman who had apparently been raped. According to the 26-page exposé, the alleged perpetrators of these murders were gauchos, the Argentine version of rootless (and occasionally violent) cowboys, and no one, the article said, was ever arrested or held accountable for these crimes.

Naturally, this more than piqued Sinay’s reporter’s instinct, and he began investigating. The years that followed the initial email from his father changed Sinay’s ideas about his family, about the Jewish farming colonies, and about his connection to his Jewish heritage.

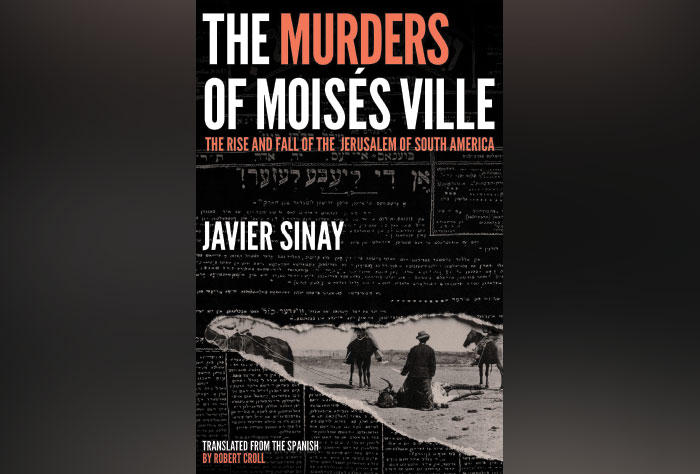

“The Murders of Moisés Ville: The Rise and Fall of the Jerusalem of South America” is an account of Sinay’s investigations into the murders. He tells us of his struggles to locate documents, to learn a bit of Yiddish, about his trips to Moisés Ville and about his conversations with locals at that village, as well as with historians and descendants of colonists. (Moisés is Spanish for Moses.)

The reader looks over Sinay’s shoulder during the twists and turns of his research, which goes back and forth in time and involves many threads.

On April 4, 2022 in a Zoom webinar hosted by the Center for Jewish History, Sinay discussed his investigations into the murders his ancestor wrote about. The event was timed to coincide with the publication of his book’s English translation.

Sinay said his research was complicated by the fact that these were very cold cases. Another barrier was that many of the documents were in Yiddish, which Sinay “did not understand a word of” when he started his research.

Moreover, as Sinay mentioned in his talk, many of the materials had been housed at AMIA (Argentine-Israel Mutual Association), the Jewish organization in Buenos Aires whose headquarters was bombed in 1994, a terrorist act that took many lives and also destroyed books, publications and other records.

Sinay said that at the time he started his research, he had only a vague notion that his great-grandfather was a journalist who, as a young man in 1894, immigrated to Argentina and settled in Moisés Ville, a Jewish farming colony several hundred miles north of Buenos Aires.

As Sinay delved into his research, he learned that his great-grandfather started the first Argentine Yiddish publication, in 1897.

During his talk, Sinay was asked why the murders were never investigated, much less punished. “Argentina is a land of immigrants,” Sinay said, “but Jews were the most exotic.” If these Jewish immigrants did not pursue justice for the murders, perhaps it was because “they were trying to keep to the official story that Argentina had opened its arms to us [Jews] and let us work the land like in biblical times.”

“Murders” is the key word of in the title of Sinay’s book, but the contents are about many other topics: Sinay’s process of investigation; what brought Jews to Argentina in such large numbers starting in 1889; and how they got from Russia to South America. (One chapter imagines the crossing.)

Sinay writes extensively about Baron Maurice de Hirsch, the wealthy European Jew who founded (and funded) the Jewish Colonization Agency (JCA), which took thousands of Jews out of shtetls and shipped them halfway around the world where they struggled to become farmers.

“Moisés Ville was the first and largest colony,” Sinay said. “But there were twenty other Jewish farming colonies in different parts of Argentina.”

During his talk, Sinay fielded questions. Someone asked what Moisés Ville is like now. “A place that was once more than 90% Jewish in the 1930s is now less than 10% Jewish,” he said.

A repeated refrain among descendants and historians, Sinay said, is that Jewish colonists “planted wheat but grew doctors.”

He added that the children and descendants of those Jews that settled in Argentine farming colonies eventually moved to Buenos Aires, where they often became professionals. A repeated refrain among descendants and historians, Sinay said, is that Jewish colonists “planted wheat but grew doctors.”

In his book, Sinay writes that after investigating the 22 murders of Jews in the late-19th and early-20th century, he came to the conclusion that most, if not all, of those murders did take place, but not in the way his great-grandfather described them.

Sinay comes to the conclusion that his journalist great-grandfather, when he wrote about the murders in 1947, exaggerated and even invented horrific details. But why? Why would a veteran journalist and archivist do that?

Sinay thinks he knows the answer. In the 1940s the wounds of the Shoah were still fresh, so he contends that his great-grandfather’s distortions were deliberate, intending to draw attention to the then-recent deaths of Jews in Europe. For Sinay, that is a justifiable reason for misrepresenting some of the details of the murders.

Thus, the final chapter of Sinay’s book is not so much about the murders but rather a touching homage to his great-grandfather, an ancestor he never met but with whom he proudly shares his journalistic DNA.

Roberto Loiederman has written more than 100 articles for The Jewish Journal. He is co-author of “The Eagle Mutiny,” a nonfiction account of the only mutiny on an American ship in modern times.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.