Passover stands apart from the other holy days in the Jewish calendar, not only because it embodies the fundamentals of Jewish faith and ethic, but also because Pesach serves as “the focal point of Jewish history” and thus “crystal[izes] the Jewish national identity and marked the birth of the Jews as a free people.”

These resonant words were penned by the late Rabbi Hayim Halevy Donin (1928-1983), the spiritual leader of Congregation B’nai David in Southfield, Mich., an adjunct professor of Judaic studies at the University of Detroit and, above all, the author of a trilogy that has introduced the rituals, traditions and practices of classical Judaism to several generations since they were first published in the early 1970s.

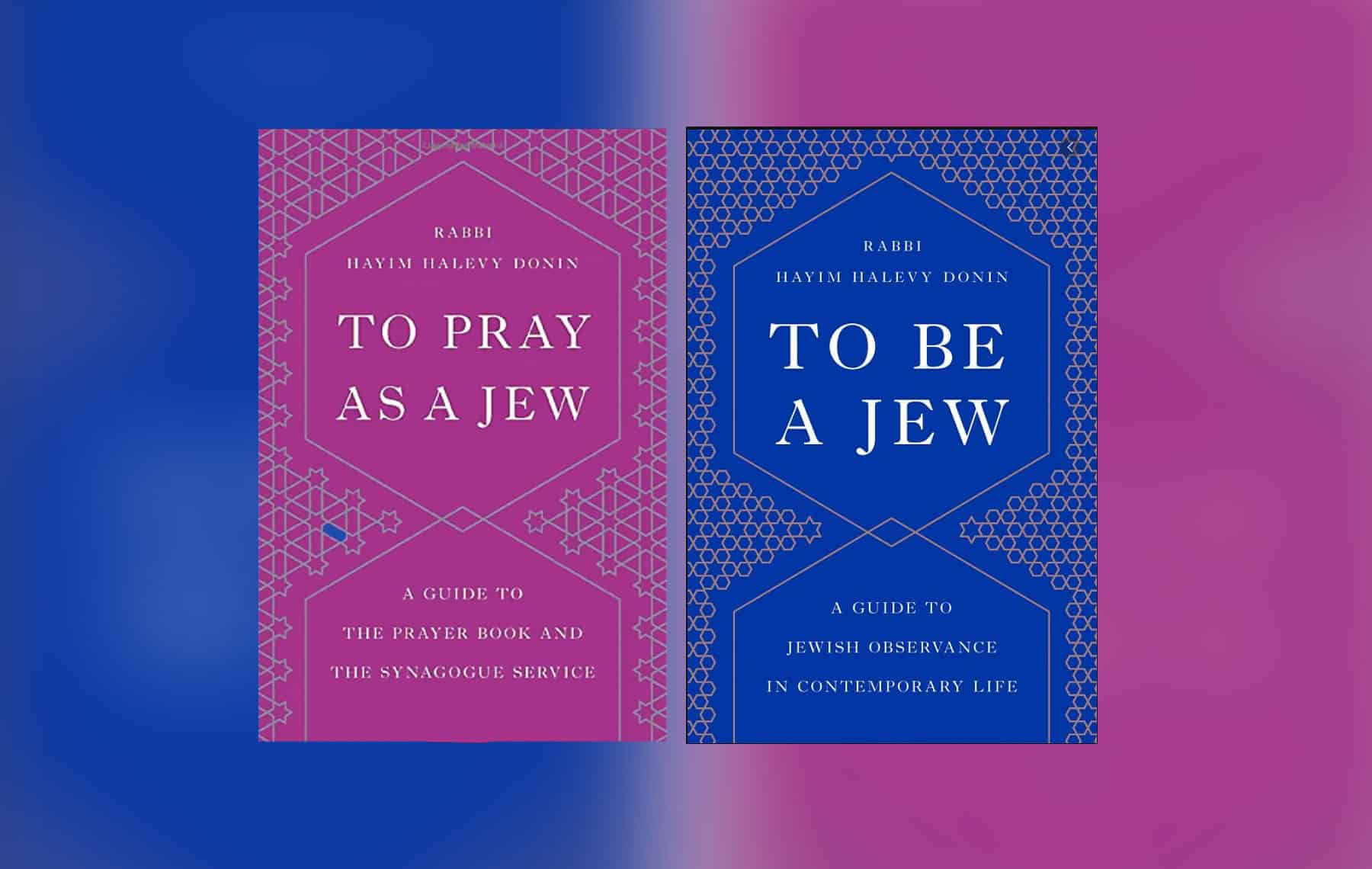

Two of the books in the trilogy, “To Be a Jew: A Guide to Jewish Observance in Contemporary Life” and “To Pray as a Jew: A Guide to the Prayer Book and the Synagogue Service,” have been reissued in handsome new editions by Basic Books, a signal event in Jewish publishing. (The third book in the series, “To Raise a Jewish Child,” also remains available from the same publisher.)

Donin himself conceived of his work as “a practical handbook on how to live a Jewish life,” but he also acknowledges that the overarching goal of the three books in the series is “to answer the constant query, ‘Why?’ ” Even a half-century ago, he recognized that many men and women who think of themselves as Jews are unaware of “the authentic values and lifestyle of the Jewish heritage,” which he describes in “To Be a Jew” as “a buried treasure.”

No aspect of Judaism is overlooked in Donin’s masterwork. Early on in “To Be a Jew,” for example, he devotes a chapter to Shabbat, “An Island in Time,” but not before he introduces the reader to the core values of Jewish history and theology, “which [do] not permit Jews to become ‘like all the other nations.’ ” He explains how Torah and halachah offer a body of law that governs the lives of pious Jews, but he acknowledges the ongoing debate that has been conducted for centuries among rabbis and sages over their meaning.

“We might compare the total panorama of Judaism to a giant jigsaw puzzle,” Donin writes in “To Be a Jew,” “which when put together shows a beautiful and inspiring picture.”

Donin’s treatment of Passover in “To Be a Jew” provides an especially enriching example of his approach. Pesach, he explains, is a festival of freedom, of course, but it was also an agricultural holiday that marked the barley harvest in ancient Israel. Above all, Passover is the only occasion in the Jewish calendar when the law of kashrut is supplemented by a special prohibition against the consumption or even the possession of unleavened bread (chametz). And so crucial are these elaborate rules and rituals, as he shows us in exacting detail, that they apply to both human beings and animals, and mere removal of chametz from a Jewish home is not sufficient; it must be burned in compliance with Exodus 12:15 (“You shall destroy leaven from your houses”).

Rabbi Hayim Halevy Donin recognized that many men and women who think of themselves as Jews are unaware of “the authentic values and lifestyle of the Jewish heritage,” which he describes in “To Be a Jew” as “a buried treasure.”

“To Pray as a Jew,” first published in 1980, carries the reader from the home to the synagogue. Here, too, Passover is the occasion for a special observance. By ancient tradition, Psalm 136, called the Great Hallel, was recited at the dedication of Solomon’s Temple and when the prayer for rain was heard and granted, but now it is uttered in the observance of Passover because it acknowledges that God “gives food to all creatures,” thus praising God “for the daily sustenance of all mankind,” as Donin explains.

So exalted is Pesach that the prayer called Tachanun is not recited at the synagogue service that precedes Passover. Donin explains in “To Pray as a Jew” that the Tachanun originated as a prayer of supplication in which “[e]veryone expressed … what lay heaviest upon his heart.” For that reason, the solemn prayer was omitted on “a day that has even the slightest festive character,” including Passover. According to the ancient sources, the practice embodies the aspiration that, when the Messiah comes, even Tisha b’Av, a day of deepest mourning, “will be turned into a festival like Passover” and “transformed from a day of sorrow to a day of rejoicing, from mourning to celebration, from a day of darkness and gloom to one of light and joy.”

Donin’s self-appointed mission was to call his readers “to return to the faith of Israel,” as he writes in “To Be a Jew.” He did not seek to innovate or reinterpret Judaism, and he saw himself as a teacher of the settled traditions. His source texts are the Tanakh and the Talmud, and he insists that there is “no substitute for studying the philosophy of Judaism as expounded or expressed in the brilliant classical works” of the rabbis and sages, “old and new.”

Still, Donin offers his three books as the starting point on the journey of return that he invites his readers to begin. The books are so clearly written, so welcoming and so respectful of his readers that they serve as keys to unlock the treasure chest that he imagines Jewish learning to be. And Donin himself conceived of his books as a way to give Judaism back to the Jews: “The Jew today is desperately needed as a Jew by the Jewish people,” he writes in “To Be a Jew.” Surely, the need is no less urgent today than it was when Donin first set pen to paper.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.