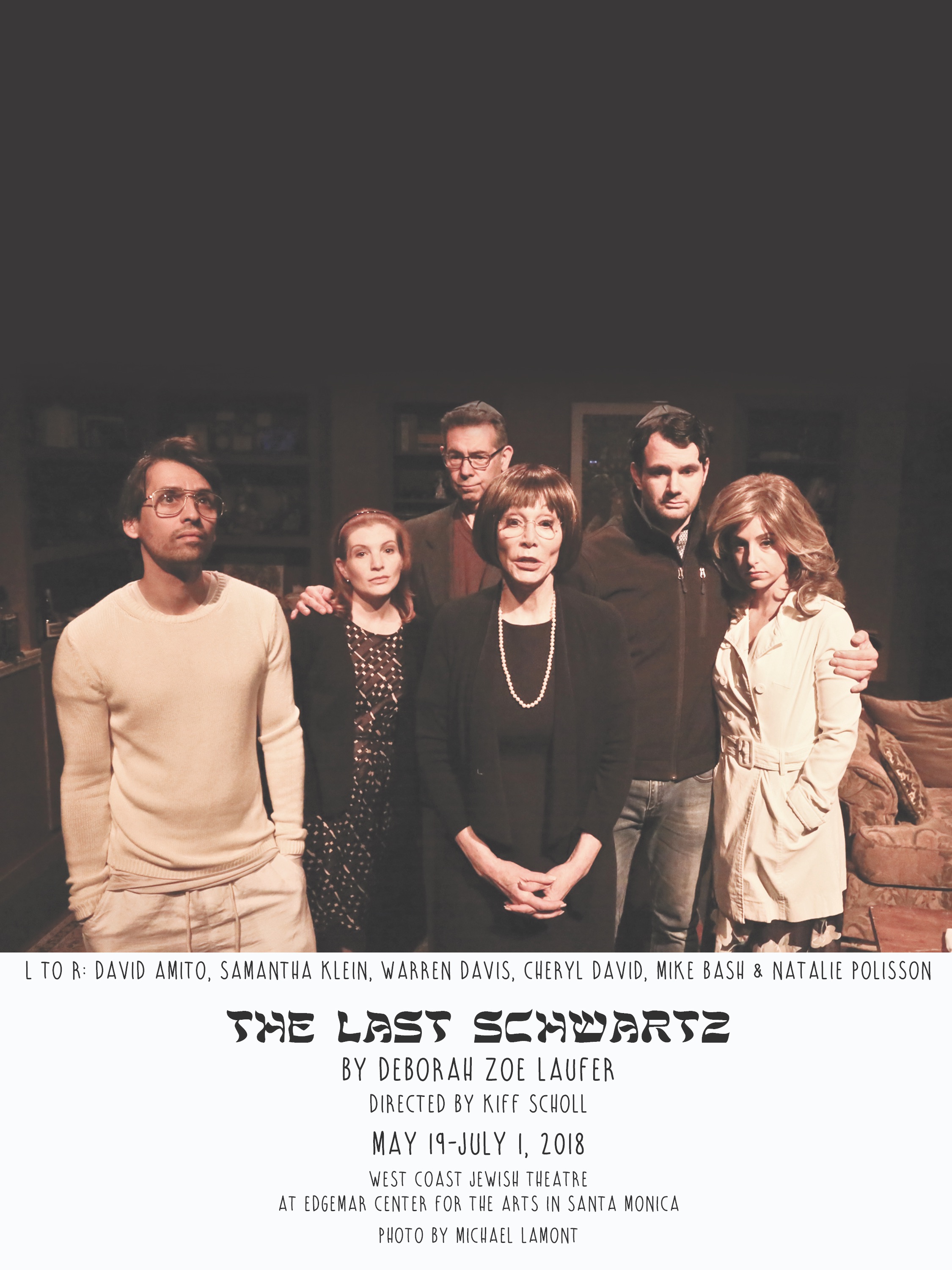

Photo by Michael Lamont.

Photo by Michael Lamont. Family dysfunction is mined to darkly comedic effect in the West Coast Jewish Theatre production of Debra Zoe Laufer’s “The Last Schwartz,” the play’s first Los Angeles staging in 10 years.

It’s set on the anniversary of the family patriarch’s death, and the adult siblings have gathered in the parental home for the yahrtzeit. Their petty arguments play for laughs, but deep-seated resentments and differences emerge that are a lot more serious.

“It’s about a family that’s losing their religion,” director Kiff Scholl said at a rehearsal with the cast. “The theme of the play is all about Jewish identity. It’s repeatedly addressed, confronted, ignored, promoted and dismissed. The family members are at different stages of relating to their Judaism.”

In the play, Norma is the self-righteous keeper of the flame. She is estranged from her son and husband and clings to tradition because it’s all she has left. Herb, successful and secular, is married to the high-strung Bonnie, who converted to Judaism and is unhappily childless after five miscarriages. Simon, an awkward, withdrawn astronomer, is going blind. And playboy Gene shows up with his shiksa starlet girlfriend Kia, scandalizing the family. However, that’s just the first of several shocking developments that force them to reevaluate their beliefs.

“I’m always looking for plays that talk about the Jewish experience in ways that not only reflect my audience but ask questions, because this is what Jews do,” West Coast Jewish Theatre Artistic Director Howard Teichman told the Journal in a phone interview. “[This play] met that criteria and fit the comedic bill as well. “We’re in such times today that we need a good laugh,” he said.

Like her character Norma, actress Cheryl David is observant. An L.A. native, she’s a member of the Stephen S. Wise Temple and sings in its choir. It was important to her to send her daughter to a Jewish school. No stranger to playing Jewish mothers, she starred in “Jewtopia” on both stage and screen over a nine-year period.

“[Norma] is so alone,” David said. “Mama and Papa are gone, and she wants the Jewish tradition to continue. When you take on a character, you have to find her humanity.”

Herb isn’t that sympathetic either, “but he’s been through a lot with his wife so I’m not so quick to judge him,” Warren Davis said of his character. “He has rejected a lot of his religion, and I can relate to that personally. I grew up in an Orthodox Jewish home in New York. My mother was very religious but my father was not. I was bar mitzvah. But I was the only Jewish kid on my block. My friends on my street were all Catholic. Being Jewish didn’t quite take for me. I had too many questions and didn’t get answers.”

“I’m always looking for plays that talk about the Jewish experience in ways that not only reflect my audience but ask questions, because this is what Jews do.” — Howard Teichman

The play’s theme strongly resonates with him. “It’s the idea of four siblings, all very different yet connected by blood, … these are the people you’re stuck with. You make the best of it,” he said. “I think anybody can relate to that.”

Sami Klein, who grew up in an observant home in Skokie, Ill., finds herself even more connected to her Judaism today. She sympathizes with her character’s plight. “No matter how bad the things she does, my heart goes out to Bonnie,” she said. “You can’t judge someone until you walk in their shoes.”

“There’s a lot of pandemonium going on in this family and Simon is alienated from it to a certain extent,” David Amito said of his character. “The idea of not being able to fit in is something I relate to.”

The son of a Jewish father whose parents lost their families in the Holocaust, and a Buddhist Austrian-Sri Lankan mother, Amito grew up Jewish but with the perspectives of both religions.

Natalie Polisson plays Kia. She grew up Christian in Indiana but recently discovered she has Jewish roots. Her mother, who was adopted, did a DNA test and learned that her birth father was an Ashkenazi Jew. “I’d love to learn more about Judaism,” she said.

While he isn’t Jewish, Mike Bash identifies with his character. “Gene has lost the faith, is not religious, and I am the same,” he said. “My father was a Catholic deacon and wanted me to do something within the clergy. He was constantly pushing me, and I went the other way.”

The cast members believe that audiences, Jewish and not, will relate to the Schwartz family and the issues they’re forced to confront. “These characters drive each other up a wall, but they’re family,” Polisson said. “Their faith brings them discord but it also brings them together.”

“Everyone goes through this stuff with their families,” Klein echoed. Compared to the Schwartzes, she said, “maybe people will feel that their families are a little

less weird.”

The show has now closed.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.