In his first decade as a filmmaker, Spike Lee wrote or co-wrote all of his films, which typically examined race in New York and featured African American protagonists. He began to diverge a bit in “Clockers” (1995), which he scripted with novelist Richard Price. Although “Clockers” was told more from the point of view of the teenage African American drug dealer than the half-Jewish, half-Italian cop played by Harvey Keitel, it led to other pictures like “Summer of Sam” (1999), with its ensemble cast of white characters from a Bronx Italian neighborhood, and the more recent “25th Hour” (2002), a film in which Lee does not have a screenwriting credit and which stars Edward Norton as a convict on his way to jail.

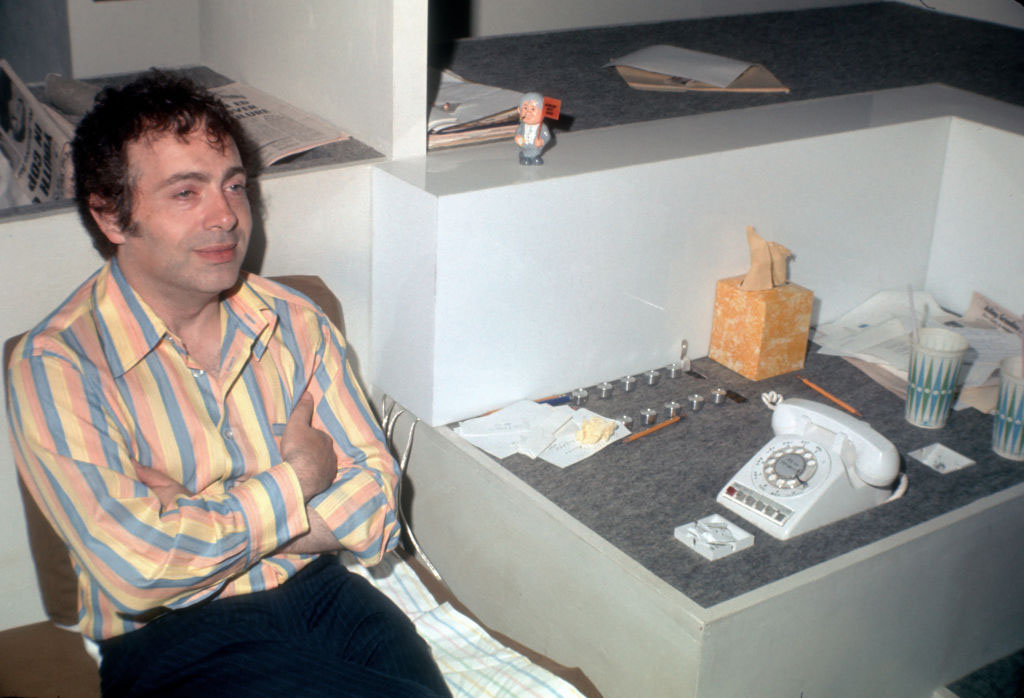

Now from the eternal Hollywood outsider comes “Inside Man,” a Universal Pictures release, scripted by a first-time screenwriter, Russell Gewirtz. Unsophisticated Jews may have once viewed Lee as anti-Semitic based on some of his statements about Ed Koch and the film industry, as well as his portrayals of Jewish music moguls in “Mo’ Better Blues” (1990), but hopefully they now recognize that this original artist, while polemical, has always been the consummate New York storyteller. And he didn’t have to prove his pro-Jewish bona fides by hiring Gewirtz, a 40-year-old Jew who hails from Long Island.

While Denzel Washington stars in the film, “Inside Man” only obliquely refers to race; rather, it calls to mind Sidney Lumet’s New York-centric crime dramas like “Dog Day Afternoon” and “Serpico.” It also hones in on what Gewirtz calls “the notion of crime and punishment.” Can a man who once did something nefarious atone for that through a lifetime of good deeds? Or will he be forever tortured?

If Gewirtz’s intent was to focus on these Dostoyevskian concerns, Christopher Plummer, who would appear to be the Raskolnikov character, provides little evidence of the moral dilemma of his literary progenitor and gets little screen time.

The film revolves more around the battle of wits between Washington’s cop, Clive Owen’s bank robber and Jodie Foster’s city power broker. But this is no ordinary heist film. It is a heist film in which no money is stolen and no people die.

The criminal mastermind behind this is Owen’s character, whose surname of Russell happens to be the first name of the 40-year-old screenwriter. One senses that Gewirtz sides with the criminal in viewing “a bad deed as being its own punishment.”

“Inside Man” experiments with sequence, cutting from the present to the future, using fast-forwards. It opens with Russell piercing the Fourth Wall and telling us some facts about his life of crime. He then says that he never repeats himself, although this direct address recurs later in the film.

Gewirtz, who has a law degree, says “my law career never really got off the ground. I didn’t want it badly enough.”

But he does understand the intricacies of city politics and the concept of a metaphorical statute of limitations, as it relates to Plummer’s character, who, like the late Deconstructionist Paul De Man and our present pope, has a past that is not easily explained away.

Still, Gewirtz says, “This is not a movie about Holocaust survivors getting retribution for the Holocaust.”

Gewirtz, who has visited the Anne Frank Museum, says, “I’m a Jewish guy who grew up in New York. I don’t need to study the Holocaust.” An autodidact, he adds, “I’m one of the guys sitting in the theater who’s seen all the movies and thinks I could write a better movie.”

“Inside Man” opens on Friday, March 24, citywide.

If Spike Lee has his legions, so does Quentin Tarantino. Though it’s been more than a decade since Tarantino burst onto the film scene with “Reservoir Dogs,” his influence remains, and not just in terms of film content or style. Like Tarantino, Jason Smilovic, a 33-year-old first-time screenwriter, whose “Lucky Number Slevin” opens in theaters on April 7, didn’t learn his craft from going to film school: “It had a lot to do with going to the local video stores,” says Smilovic by phone.

In fact, Smilovic’s father owned a video store in Long Island. When he was unemployed for about a year, Smilovic would routinely watch two movies a day.

Even over the phone, Smilovic reveals an engaging personality and is quick with a quip. Of getting kicked out of SUNY-Buffalo, he says, “It was hard to get to class with all the snow.”

Of his time at the University of Maryland, he says, “I couldn’t even tell you if I got a B.A. or a B.S.”

Not surprisingly, he finds writing a screenplay to be “a lot like telling a joke. It has more to do with the delivery and the telling than any required structure.”

And he delivers a unique riff on the fabled gangland picture in “Lucky Number Slevin,” a film produced by the Weinstein Company, whose two chieftains also first spotted Tarantino. The film features two warring gangs, one headed by “the Rabbi” (Sir Ben Kingsley) and the other by “the Boss” (Morgan Freeman), who battle from towering edifices across the street from one another in New York’s West Village.

The Rabbi is indeed a rabbi, but he is also a gangster. Smilovic says that he was intrigued by that dichotomy within a single character.

“Let’s face it. Jews lack the coordination to be gangsters,” he says, though he is aware of the history of Jewish gangsters going back to the first half of the last century. “We had a different level of manual dexterity back then. When you take a minority group like Jewish culture, which is wholly predicated on intellectualism, we always look up to physical prowess, to guys who know how to use their hands.”

The film’s director, Paul McGuigan, a Scotsman perhaps best known for directing “Gangster Number 1,” had never before directed a film with a Jewish theme. Speaking in a thick Scottish accent from his car phone, McGuigan says that while so many scripts he sees are “quite generic,” Smilovic showed a “refreshing” originality by not passing judgment on any of his underworld figures. McGuigan calls the screenwriter “quite a character. He goes to bed and watches two movies.”

That knowledge of film lore informs “Slevin.” Of course, there are the homages to Tarantino. As in “Pulp Fiction,” the story is told out of sequence, with alternate scenarios, multiple endings, and it even includes a hit man named Goodkat, played by “Pulp Fiction” veteran Bruce Willis, who, like Clint Eastwood’s Man With No Name, plays the two warring families against each other.

Beginning with a race heist gone wrong, “Slevin,” released by the newly reopened distribution arm of MGM, also pays tribute to “The Killing,” Stanley Kubrick’s classic film on that subject from the 1950s, which Smilovic calls one of his favorite movies.

As the opening credits of ” Slevin” roll, the camera moves down past Hebrew letters and circled numbers. It takes some time before we realize that these cryptic numbers and letters pertain not to the kabbalah but to the ledger of a Jewish bookie.

A series of murders follow. It is only after a denouement evocative of “The Usual Suspects” that we realize why they involve Slevin, the title character played by Josh Hartnett, who must endure several broken noses throughout the film.

The script is filled with rich dialogue and irony. Characters use terms like “conundrum” and “notwithstanding,” formality that can’t help but point to the underlying wit of the screenwriter, who says he “writes what I’m feeling at that moment. I do my best writing when I’m not thinking too much. I try not to have too much intention.”

“Lucky Number Slevin” opens on Friday, April 7, citywide.