The Lawfare Project held a webinar on November 2 explaining the legal rights that Jewish students have on campus to fight antisemitism.

Brooke Goldstein, who heads The Lawfare Project, began the webinar by calling the current climate “unprecedented times” and saying that the warnings for 10 years about terror-affiliated groups on campus and professors are “materializing in ways that we could only imagine in our worst nightmare.”

“We are all very concerned,” she said.

Goldstein said that “now is the time for a Jewish civil rights movement” and pointed out that “litigation is always the last resort.” She also argued that a lot of university administrators want to help so it’s “important to work with them to guide them on what to do.” The Lawfare Project works with 680 major lawyers who provide pro bono work for the Jewish community.

Ziporah Reich, director of litigation for The Lawfare Project, said that they have received “an overwhelming amount of calls” from students “suffering” in current campus climate. “People are livid with what’s going on,” she said. But there might not always be legal action available in these circumstances, Reich explained, comparing instances of antisemitism on campus to a terrible headache. A doctor may not be able to provide surgery to cure a bad headache, but sometimes a mild headache could turn out to be a tumor that a doctor can remove.

As it pertains to antisemitism on campus, the law in question is Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, which states that any institution receiving federal funding cannot discriminate based on race, ethnicity or national origin. “That applies to every college in this country because almost every college … receives some sort of federal funding,” Reich said. Under the law, schools have to allow all the students on campus to have an equal opportunity to avail themselves with whatever the college has to offer, Reich said, so if college has a gym on campus, you have a right to use that gym. If college has a tabling policy, you have a right to table.

“The key is that if the school itself deprives you of the right or another student deprives you of the right … then it’s actionable,” Reich said. For instance, in a scenario in which pro-Palestinian protesters are standing outside the school gym which signs accusing Israel of genocide, then it is not legally actionable if you can still walk into the gym. But if those protesters try to block you from entering the gym by forming a human chain, then it becomes actionable, Reich explained. In such a scenario, you have to alert the school since they don’t always know what’s going on, at which point it becomes the school’s responsibility to remove the human chain blocking you from entering the gym. If they don’t, then you truly have a valid legal case against the case, per Reich. A more murky scenario would be if you’re using the school’s gym equipment and pro-Palestinian protesters are waiting to the machine and are whispering anti-Israel rhetoric into your ears.

Other legally actionable examples would include pro-Palestinian protesters disrupting a pro-Israel speaker’s speech by using loud megaphones to drown them out, pro-Palestinian students ripping down posters and if someone touches you without your consent, such as pushing you away. Reich also put forth an example of someone shouting pro-Hamas rhetoric, such as calling Hamas’ actions on October 7 “heroic” or calling the terror organization “freedom fighters,” in the university quad as “potentially” actionable, but Reich cautioned that “this particular point has not really been litigated in court when it’s this nuanced.” But The Lawfare Project is prepared to litigate it if it happens, she said.

Reich stressed that it’s important to understand the policies of a school, particularly if they’re private schools, which she says have more leeway than public schools. If the schools aren’t equally enforcing their policies, then that is legally actionable.

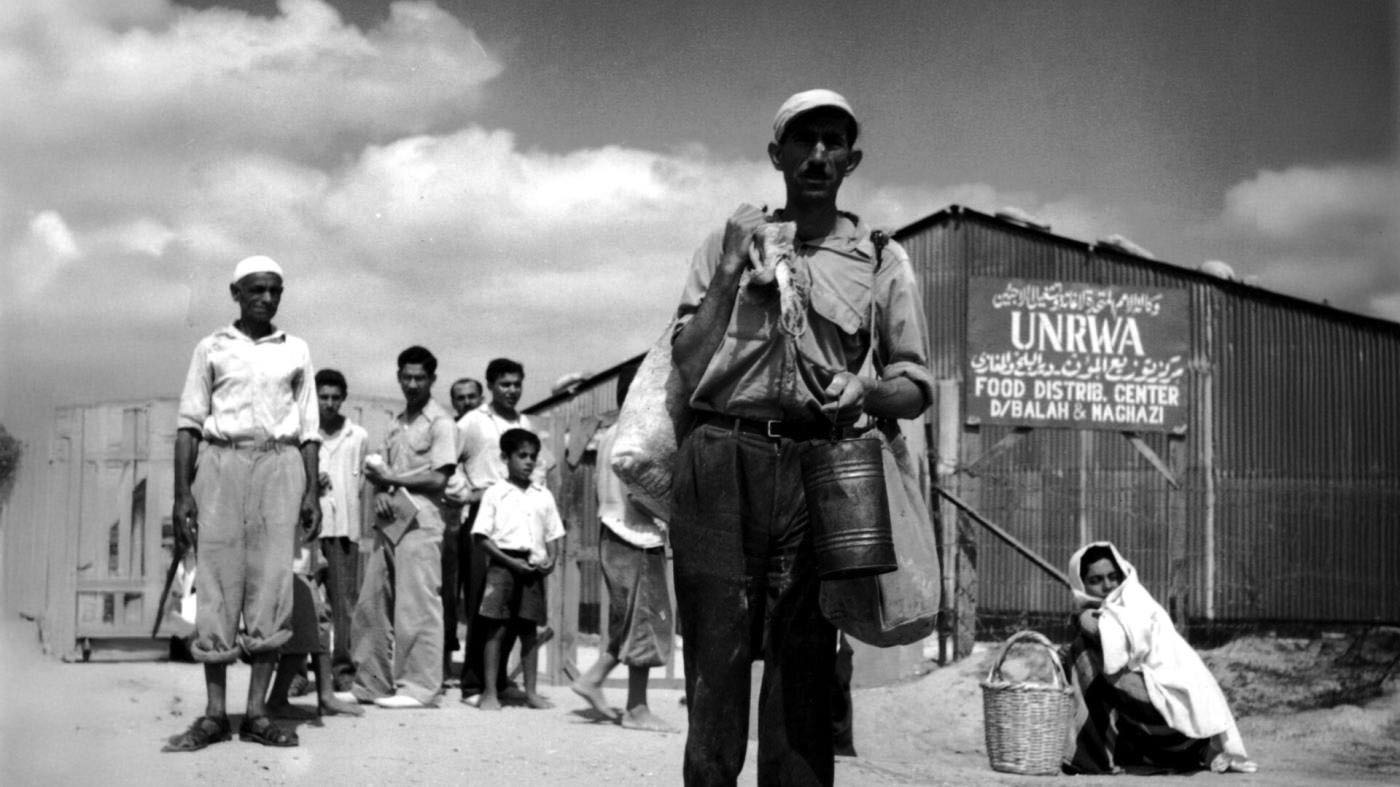

Lawfare Project Senior Counsel Gerard Filitti proceeded to discuss pro-Palestinian student groups like Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP) and Within Out Lifetime-United for Palestine (WOL Palestine). Filitti said that it’s for the FBI to decide if these student groups have ties to terror organizations, but did point out that Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’ (R) decision to ban National SJP (NSJP) was based on the argument that NSJP was providing material support to a terror organization by saying “we are all part of the resistance.” However, Filitti viewed DeSantis’ action as a “political stunt,” as DeSantis’ language was careful enough to where members of NSJP chapters could simply reapply to have a new pro-Palestinian group on campus, so long as it’s not under the NSJP umbrella.

Filitti did say there are “connections between these student groups and other terrorist affiliates,” as they have invited Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) member Leila Khaled to speak remotely on numerous occasions. But Filitti pointed out that it’s not illegal to speak to bad people, it’s only illegal when you support them and fundraise for them.

Filitti also argued how there’s a correlation between funding from Middle East countries and antisemitism on college campuses, although he acknowledged that there’s no proof of causation. That said, if colleges are receiving billions in dollars from countries like Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the “question becomes what is that money paying for.” The law currently requires universities to disclose foreign money––although Filitti said this law is not being enforced properly––but doesn’t require universities to disclose where it’s going. There are “at least a dozen bills” in Congress right now that are working to ameliorate this situation, Filitti said, and that The Lawfare Project is doing their own work to try and expose where such money is going.

The Lawfare Project senior counsel went onto address the viral video from Harvard University showing a Jewish student being surrounded and cornered by pro-Palestinian protesters; Filitti argued that the video shows evidence of false imprisonment and that the protesters laid their hands on the Jewish student without the student’s consent. “These are things you follow police reports for,” Filitti said.

Filitti urged people to document what’s happening because “if it’s not in writing it didn’t happen.”

Reich later told people not to be concerned about speaking out or taking legal action out of fear of retaliation, pointing out that retaliation in and of itself is illegal.

The Lawfare Project members were asked during a Q&A session about what can be done about anti-Israel curriculum being taught in class; Reich replied that such curriculum is “what laid the fertile ground for what is happening now.” However, academic freedom protects the right of anti-Israel teachers to teach what they want in class. “The school may have to let the anti-Israel prof spew her rhetoric, but they are breaking the law if they don’t allow the pro-Israel professor to say his thing,” Reich said.

The problem, in Reich’s view, is that too many Jewish professors are afraid to speak up due to a hostile campus environment. The best way to combat this, Reich argued, is for Jewish students to “rally around” these professors.

Reich also said during the Q&A that it is usually within universities’ interests to settle when faced with a legal claim because if they lose, they are forced to pay attorneys’ fees, so it works in the favor of the plaintiff to get what they want.

Benjamin Ryberg, chief operating officer and director of research for The Lawfare Project, addressed questions regarding legal ramifications of doxxing. Doxxing, Ryberg said, is when somebody posts “personally identifiable information online.” Around 11 states have laws against doxxing, though California’s broad if some personal information was posted with the intent of putting someone’s safety in jeopardy, whereas other states have anti-harassment laws that are triggered from doxxing. Ryberg argued that the trucks that have gone around identifying people who signed anti-Israel statements like the infamous Harvard letter are not examples of doxxing because that is simply bringing to light publicly identifiable information.

Asked about filing complaints to the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights (OCR) vs. bringing something to a court of law, Goldstein argued in favor of the latter, as in her view OCR is “politicized.” Goldstein pointed to an “outstanding complaint” they filed on behalf of a client at Columbia University who was allegedly spat on and called a “dirty Zionist” in the university quad; this happened four years ago, Goldstein said.