I’ve thought way too much about terror this week. As I sat down to write this, I tried to do a rough accounting. What’s a clever unit of measure for moments spentobsessing about terror? An osama? No, that gives the cretin too much credit. A chertoff? Better. A chertoff is a full cycle of terror-think.

It works like this: On Sunday at LAX, the guy ahead of me at airport security is swarthy. He’s traveling alone. His duffel bag is overloaded with clothes. He seems nervous when the inspector tells him to put his laptop in a separate busboy bin. I had just finished reading a long article on the foiled airplane bombing plot in Britain. Should I even get on this flight? What if he turns out to be my rowmate and he takes out a bottle of … liquid? Then what would I do?

My mind races through the scenerios: I freeze? I scream? I tackle him? I talk him out of it….

There, that was a chertoff. A moment of my life at the United Airlines terminal devoted to worrying about the whethers and what-ifs of terror, a moment I won’t get back. Boy, how many chertoffs did I rack up this week?

As soon as I got to work Monday, I logged onto the Christian Science Monitor Web site. Each day the Monitor has posted another installment in the story of Jill Carroll, the freelancer on assignment for the paper who spent weeks in captivity at the hands of Iraqi insurgents. It is gripping, cliffhanger reading. When Carroll’s kidnappers weren’t threatening to kill her, they sweet-talked her about converting to Islam. No single piece of reporting has taken us as close to the thoughts and behavior of the men, women and children who hate America in Iraq. Carroll was witness to at least an inkling of what the kidnapped and murdered Wall Street Journal reporter Daniel Pearl must have experienced. Of course, as I read Carroll’s testament, I spent even more chertoffs wondering how I would react, how any of us would react, faced with such uncertainty and fear.

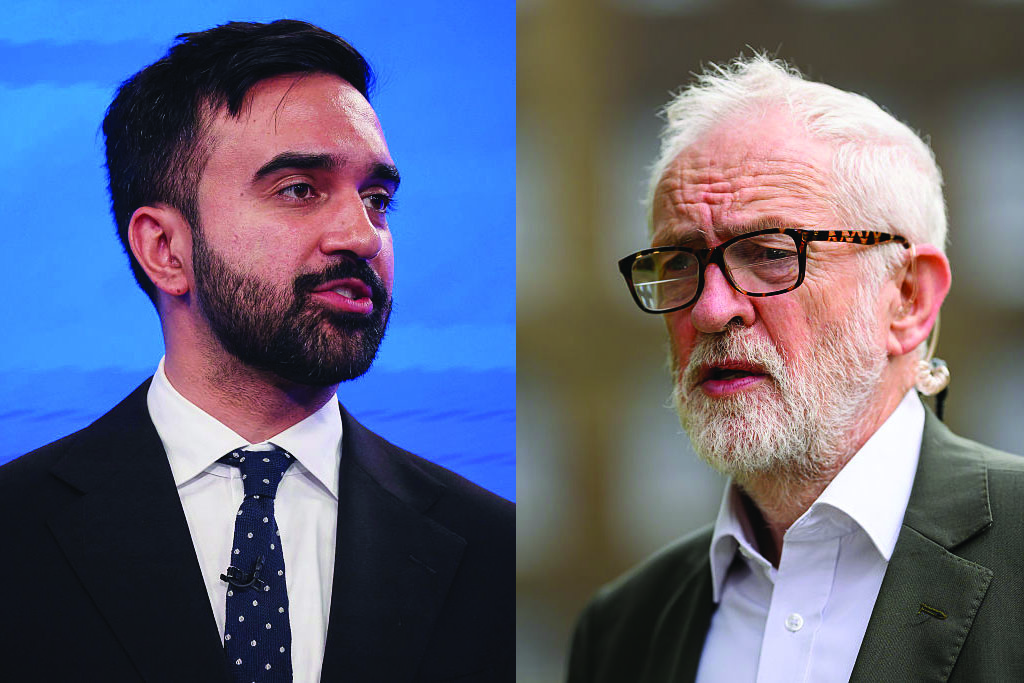

Pearl himself was never far from my thoughts this week. For the third year in a row, The Jewish Journal hosted two Daniel Pearl Fellows in International Journalism. Each year the Pearl Foundation selects journalists from developing countries to spend six months working at an American newspaper. At the end of the fellowship, the journalists spend a week at The Journal. The idea is to get a more rounded insight into American Jewry than what’s available in their home country. Shahid Hussain Shah, a quiet, professorial 29-year-old came to us from The News in Pakistan. Ghanashyam Ojha, 34, a Hindu from Nepal, was the first non-Muslim Pearl Fellow. An editor for the Kathmandu Times, he spent his fellowship at the Berkshire Eagle, the small-town paper where Pearl got his start as a reporter.

So a Hindu, a Muslim and a Jew met in Koreatown. Most of our conversations over the course of the week revolved around terror. Shah explained that in his country, terror takes root among a relatively small group of religious extremists whose symbiotic relationship with the military rulers practically ensure the problem will never go away. The terrorists use the Quran to justify acts that about 70 percent of Pakistanis want nothing to do with. Pakistan’s ruling generals use the terrorists and their supporters — just 10 percent of Pakistanis, Shah said — to put pressure on India, the West and domestic critics. An “uncommitted” 20 percent swings for or against the extremists, depending on external factors — what they read about America or Israel, for instance.

Shah was able to parse Pakistan according to its ethnic and political divisions in a way our own press never does. But the bottom line, he said, is that, “Pakistan is not a country with a military dictatorship. It’s a military dictatorship that has a country.”

Until democracy comes to Pakistan, Shah sees little hope for stemming terror.The irony is that if it weren’t for an act of terror of the worst kind, the three of us wouldn’t have gotten together in the first place. The Pearl Foundation has managed to somehow find redemption in an unredeemable act.

But it didn’t occur to me until our last day together that at my prompting the three of us spent far too much time talking about terror and its related issues, and far too little about the other 99.9 percent of the world.

I took them to the original Wilshire Boulevard Temple sanctuary and watched their excitement stepping into a synagogue for the first time. The maintenance men flipped on the lights, and we stood alone in the cavernous, ornate sanctuary, speaking softly in front of the ark. We could talk about other things.

Ohja, the Hindu, had big questions.

“So what,” he asked, “is Judaism?”

The doctrinal differences between the three monotheistic religions were beyond baffling to him. There are 900 million Hindus in the world, adhering to a highly syncretic religion of multiple gods, multiple traditions and numerous texts.

When I explained that Jews don’t believe in Jesus, his obvious next question was very Hindu: “Aren’t there Jews and Christians working together to figure out how they can all believe in Jesus?”

“You see,” Shah said, “It’s not so simple.”

I took them to Cantor’s Deli. The menu has, oh, about 10,000 items.

“What is there to eat?” Ohja asked, again a bit lost.

“Get the lox and bagels,” I said. “It’s the standard thing.”

Shah asked what lox is.

“Smoked salmon,” I answered.

“What’s salmon?”

The food came and I watched Shah take his first bite: smoked fish, cream cheese, bagel. His face contorted in disgust: “What did you say this is?””You can order something else,” I offered.

No one said intercultural understanding was easy.

The next day I was back to terror. I racked up several more chertoffs spending the afternoon hearing … Michael Chertoff. The director of Homeland Security was in town, and I caught up with him at a discussion he held for the Pacific Council on International Policy.His message was twofold:

- America is under constant threat from a network of world terrorists bent on killing us and destroying our way of life, and

- Don’t worry too much, we’re on top of this. He urged the audience not to back off in its vigilance or support for anti-terror efforts: “We only make progress … when we become relentless in pursuing them.”

Chertoff is a former prosecutor, judge and the son of rabbi, and his demeanor combines elements of all those professions. His choice of words seems designed to make audiences aware but not anxious, calm but not comfortable.

Several thoughtful analysts, such as James Fallows in The Atlantic, have been writing in recent weeks about the need to call the War on Terror off, to declare victory — there hasn’t been another Sept. 11 since Sept. 11 — treat terror as a law-enforcement problem, and deprive Osama of the high-profile rhetoric and reaction that only raises his profile. But Chertoff dismissed the idea.

“It is a mistake to declare the war over when the other side thinks it’s still fighting,” he said.

What he didn’t say, of course, is that for all our worrying about terror, the chances of anyone of us dying in a terror attack is miniscule: one in a million, according to the RAND Corporation’s Brian Michael Jenkins (I heard him speak earlier — but that’s another column). Every 12 miles you drive in your car puts you at the same level of risk.

On our last day together, I took Ohja and Shah to the Venice Boardwalk. It was a perfect Venice afternoon — sunny and warm, all the potheads, freaks and hucksters just where they should be. The night before, at a public dialogue I led for the Los Angeles Press Club, Shah repeated his statements on the totalitarian nature of his country. We both noticed there were two Pakistani-looking men in the audience who came and left without a word.

“Aren’t you worried about going back?” I asked.

“They want me to be afraid,” he said. “But I can’t. I have the example of Daniel Pearl, and I can’t worry about them.”

The truth is, all my wasted chertoffs are mostly that — a waste. Very few of us are really at risk, and those of us who aren’t would do better supporting those who truly are: the Danny Pearls of the world, people like Jill Carroll and people like Shahid Shah.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.