It all begins with a dusty box in an attic. An elderly couple in Tennessee are moving, prompting them to sift through the odds and ends they have collected in 50 years of marriage. Some unknown person has written on this box — “Important papers do not throw away!” — and the wife, Suzie Lazarov, opens it to find dozens of old handwritten letters, telegrams, black-and-white photos, and a diary. She removes the first letter and reads:

“Hebron, Palestine

“October 5, 1928

“Dear Folks

“Rest assured, nothing that I write or that words can describe can do justice to the beauty of Palestine.

“Devotedly, Dave.”

The writer is Suzie’s late uncle, David Shainberg, a relative she has never met. She knows only that he moved in 1928 to British Mandatory Palestine to study in a yeshiva, and that he was killed there the following year. She now removes his letters, more than 60 of them, to read his vivid weekly descriptions about walking the ancient alleyways of Hebron’s Jewish Quarter, Jewish holidays and weddings attended by local sheikhs, the friendly relationships that have developed between Arab and Jewish neighbors.

The final letter is dated August 20, 1929. In it her uncle tells his father about visiting Jerusalem’s Western Wall to observe Tisha b’Av, amid great tension in the city. For many months, Arab Jerusalem’s leader, the Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini, had been agitating against Jews trying to pray at the wall, claiming they were plotting to destroy Al-Aqsa Mosque. Jewish worship at the wall became increasingly perilous or impossible, and Jews responded in various ways — some by founding a committee, others by peacefully demonstrating with a paramilitary youth movement founded by Vladimir Jabotinsky — causing mainstream Jewish leaders to worry about provoking the British. At a mass meeting organized by the mufti, Muslims pledged to defend Al-Aqsa “at any moment and with the whole of their might.” David, viewing the scene with some friends from Hebron, felt the crisis had reached “almost the breaking point.”

“As we walked along Jerusalem’s streets,” he wrote, “we could almost imagine the streams of Jewish blood flowing at our feet, the horrible scenes of slaughter. Jewish sages, budding youth, tender babes in their mother’s arms, all killed by the barbaric sword of the enemy.”

His words were prophetic. Four days later, David was among the almost 70 Jewish men, women and children slaughtered in his beloved adopted hometown of Hebron.

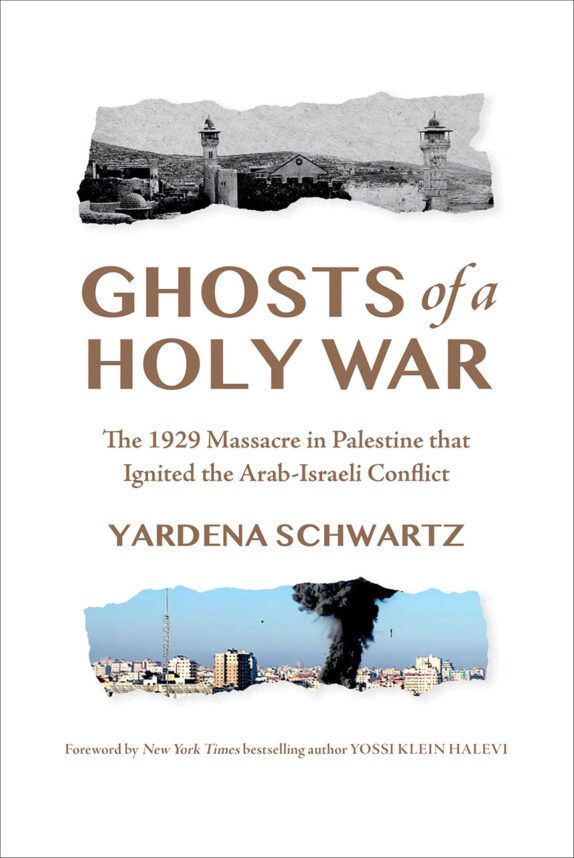

Yardena Schwartz has taken David’s letters and diary, given to her by Suzie’s daughter Jill Notowich, as the springboard for an astonishing work of history. The first third or so of “Ghosts of a Holy War” centers on the pogrom in Hebron — an event that seemed to express the limits of human barbarity, until it was eclipsed by later horrors against the Jews. So much of what unfolded in Hebron will remind the reader of Oct. 7 — beginning with the certainty of so many Jews that since they believed in peace, no harm would come to them.

So much of what unfolded in Hebron will remind the reader of Oct. 7 — beginning with the certainty of so many Jews that since they believed in peace, no harm would come to them.

“Nonsense!” said Eliezer Dan Slonim, one of Jewish Hebron’s leaders, after two women reported having overheard Arabs in the marketplace laughing about the terrible things they would do to Jews on the coming Saturday.

“Such a thing will never happen here,” Slonim insisted. “We live in peace among the Arabs. They won’t let anyone hurt us.” As alarming rumors and reports from other regions swirled and grew in intensity, the Jewish leaders of Hebron insisted that they lived in the safest place in Palestine.

“Such a thing will never happen here,” Slonim insisted. “We live in peace among the Arabs. They won’t let anyone hurt us.” As alarming rumors and reports from other regions swirled and grew in intensity, the Jewish leaders of Hebron insisted that they lived in the safest place in Palestine.

One of the most heartrending aspects of that Black Sabbath, Aug. 24, 1929, is the shocked sense of betrayal expressed by so many of its victims. “Have mercy on us,” pleaded Yitzhak Abushdid, a tailor, when rioters chanting “Slaughter the Jews” stormed into his home. He had made clothes for many of them. “Aren’t you our friends?” The mob strangled him with a rope and ran a sword through his father.

Meanwhile the British police and governing authorities did virtually nothing. When the mob began its rampage and Jews appealed to the police chief, he yelled at them to go in their homes, saying, “You Jews are to blame for all of this.” Arab policemen joined the bloodletting. Only after many hours, when the pogromists threatened to kill the police chief too, did he order his policemen to fetch their guns from the station. The slaughter ended moments after police opened fire — too late for Hebron’s Jews.

There is an eerie similarity about atrocities carried out against Jews in different times and places. The weapons and techniques become more sophisticated, culminating in the Nazis’ industrialized mass murder, but the spirit is always the same. Leon Trotsky described early 20th-century Russian pogromists rushing through a town, “drunk on vodka and the smell of blood,” each man ecstatic to discover that “there exist no tortures” at which he need stop. The same joy in evil was present in Hebron. One of many evocative photographs in Schwartz’s book captures it: The mob on Aug. 24, at its center a man in traditional Arab dress brandishing what looks like a long scimitar. He is exultant, arms upraised. It’s the same glee we saw over Hamas’ GoPro footage in 2023, as the terrorists machine-gunned cars containing children to the droning chant “Allahu Akhbar.” We’ve seen something of this intoxication across the West, that thrill at “the smell of blood,” by would-be pogromists enthusing “Long live Oct. 7.”

But of course there are important differences between Hebron 1929 and southern Israel 2023, most essentially that there is now a Jewish state pledged to safeguard its people’s lives. Another is that for all the horror of Hebron’s Black Sabbath, at least 250 Jews were rescued that day by their Arab neighbors, many at risk to their lives. Schwartz honors these Arabs, such as an elderly man, Abdul Shaker Amer, who guarded a home containing a rabbi, his children and a dozen other Jews. Abu Shaker dared the rioters: “Kill me! The rabbi’s family is inside, and they’re my family too.” All survived. Such stories provide a small measure of hope for humanity.

Sadly, similar accounts have not reached us from Oct. 7. The descendants of Arabs who saved Jews in 1929 must hide this fact from other Palestinians today, or be condemned as traitors. The three pogromists who were hanged by the British for their crimes, on the other hand, are honored to this day as martyrs.

Schwartz remarks that “If Arab leaders had hoped to weaken the threat of Zionism, the riots of 1929 had the opposite effect, accelerating the very process they wished to forestall.” The British responded to the pogroms throughout Palestine with classic victim-blaming, claiming the Jewish community provoked the Arabs with their (peaceful) demonstration at the Western Wall. A few years later, in 1936, the Arab High Command, a group of Arab leaders headed by al-Husseini, called for a general strike and boycott of Jewish products to protest Jewish immigration into Palestine. This protest soon escalated into violence, the Arab Revolt of 1936-39. In response, the British enacted increasingly strict restrictions on Jewish immigration into Palestine — this as the Nazis were becoming a graver threat.

“This was the moment,” Schwartz writes, “when many Zionists became militaristic in their efforts to establish a Jewish state. The seeds of the Jewish rebellion against the British that ultimately ended the British Mandate were planted here, in the aftermath of the Hebron massacre.”

I’ve been to Hebron. I was struck by its stillness, so much in contrast to the rancorous militarized zone I was expecting. I visited its museum, where I learned about the pogrom. I met the settlers (a few of them anyway), and found decent, good-humored human beings. They were devout, dedicated to maintaining a Jewish presence in Judaism’s second-holiest city, and, from what I can tell, wanted to live in peace with their Palestinian neighbors — but had a machine gun ready in the living room, just in case. I left Hebron not knowing what an answer for it might be, but thinking I understood why the settlers feel the way they do.

Schwartz’s book has deepened that sense, while adding layers of necessary, but often vexing, complexity. She handles one of the thorniest issues faced by today’s Zionist — the settlement movement — with honesty and nuance. On the one hand, she provides a pointed counternarrative to critics who claim that Israel has been hellbent throughout history on taking over Palestinian land. In fact, the reader learns, far from rushing in to settle the lands won in 1967, Israel tried to conciliate the Palestinians by staying out. They hoped that if they turned over these territories, the Palestinians would in return grant peace. Moshe Dayan told the BBC, “We’re waiting for a phone call from the Arabs” — the one that would finally end the conflict.

Schwartz provides a pointed counternarrative to critics who claim that Israel has been hellbent throughout history on taking over Palestinian land. In fact, the reader learns, far from rushing in to settle the lands won in 1967, Israel tried to conciliate the Palestinians by staying out.

As a result there were zero Jews in Hebron, the burial place of Abraham and Sarah, for 12 years after 1967. Eventually religious Zionists impatient to return to the city might be forgiven for feeling that Moshiach was likely to arrive before peace with the Palestinians did. In 1979 they took matters into their own hands, sending a brigade of women and children into an abandoned Hebron building — one targeted in the 1929 massacre. The government was forced to decide whether to forcibly evict Jewish women and children from a place steeped in such history, and unsurprisingly, didn’t have the stomach for it. Hebron’s settlement community was born.

So that’s on the one hand. On the other, Schwartz writes about visiting a Palestinian — the descendant of an Arab who saved Jews in 1929 — on the Palestinian side of Hebron. She sees Israeli police impose seemingly arbitrary rules that make Palestinian lives harder, sees and hears about provocative behavior by settlers. During a festival for Shabbat Chayei Sarah, she sees marching Jewish teenagers give Palestinians the finger and vandalize their cars. When she confronts the teenagers, they look at her as if she’s crazy. “They’re killing us, and you worry about their cars?”

Which brings us back the other, first, hand: The current mayor of Hebron, Tayseer Abu Sneineh, who Schwartz interviewed for the book, was convicted of murdering unarmed Jews in 1980. (A spoiler of the interview: He isn’t sorry.)

Schwartz doesn’t claim to know what the answer is, but pans out to provide a full, lucid account of the entire Arab-Israeli conflict. Do not think, as I did at first, that this book is “about Hebron,” or one bloody episode in the Jewish people’s history. It is an overview to it all, from British Mandate Palestine to the massacres of Oct. 7.

The reader gets an appreciation of how much of this blighted history can be laid at the feet of one especially malevolent man, Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini. The British elevated him to his position of enormous power after he incited riots in 1920, and decided to keep him there despite his central role in the pogroms of 1929. He was the man who ensured that the 1937 partition plan proposed by the Peel Commission would fail: Although many Arab leaders supported the plan, the mufti rejected it and threatened to have any Arab who supported it assassinated as a traitor. Any possibility that a two-state solution might be peacefully accepted vanished.

The reader gets an appreciation of how much of this blighted history can be laid at the feet of one especially malevolent man, Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini.

The reader also learns about the close, mutually respectful relationship between the mufti and Adolf Hitler. The mufti lived comfortably from 1941-45 in Berlin, where he was a fixture of the Nazi propaganda machine and may have been one of the most lavishly paid men on the Nazi payroll. In these days when every political opponent is deemed to be just like Hitler, it bears emphasizing: the godfather of Palestinian nationalism was literally a Hitler-lover.

The animating spirit of the defeated Reich lived again on Oct. 7. And in echoes of Hebron, Jews who got along well with Arabs were the main victims. The Jews who perished on that day were peace-lovers who drove Palestinians to doctors’ appointments, Jews who only wanted to dance at a music festival dedicated to peace. No matter how much you’ve read about Oct. 7, I defy you not to cry when you read Schwartz’ chapters about that terrible day and its aftermath.

Schwartz writes with clear, luminous prose, demonstrating the sense of timing and drama of a novelist. Much as you might wish that much of what you read were fiction, you will be glad to gain from this book a better sense of the bloody road to Oct. 7.

Kathleen Hayes is the author of ”Antisemitism and the Left: A Memoir.”

Hebron, 1929: What’s Past Is Prologue

Kathleen Hayes

It all begins with a dusty box in an attic. An elderly couple in Tennessee are moving, prompting them to sift through the odds and ends they have collected in 50 years of marriage. Some unknown person has written on this box — “Important papers do not throw away!” — and the wife, Suzie Lazarov, opens it to find dozens of old handwritten letters, telegrams, black-and-white photos, and a diary. She removes the first letter and reads:

“Hebron, Palestine

“October 5, 1928

“Dear Folks

“Rest assured, nothing that I write or that words can describe can do justice to the beauty of Palestine.

“Devotedly, Dave.”

The writer is Suzie’s late uncle, David Shainberg, a relative she has never met. She knows only that he moved in 1928 to British Mandatory Palestine to study in a yeshiva, and that he was killed there the following year. She now removes his letters, more than 60 of them, to read his vivid weekly descriptions about walking the ancient alleyways of Hebron’s Jewish Quarter, Jewish holidays and weddings attended by local sheikhs, the friendly relationships that have developed between Arab and Jewish neighbors.

The final letter is dated August 20, 1929. In it her uncle tells his father about visiting Jerusalem’s Western Wall to observe Tisha b’Av, amid great tension in the city. For many months, Arab Jerusalem’s leader, the Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini, had been agitating against Jews trying to pray at the wall, claiming they were plotting to destroy Al-Aqsa Mosque. Jewish worship at the wall became increasingly perilous or impossible, and Jews responded in various ways — some by founding a committee, others by peacefully demonstrating with a paramilitary youth movement founded by Vladimir Jabotinsky — causing mainstream Jewish leaders to worry about provoking the British. At a mass meeting organized by the mufti, Muslims pledged to defend Al-Aqsa “at any moment and with the whole of their might.” David, viewing the scene with some friends from Hebron, felt the crisis had reached “almost the breaking point.”

“As we walked along Jerusalem’s streets,” he wrote, “we could almost imagine the streams of Jewish blood flowing at our feet, the horrible scenes of slaughter. Jewish sages, budding youth, tender babes in their mother’s arms, all killed by the barbaric sword of the enemy.”

His words were prophetic. Four days later, David was among the almost 70 Jewish men, women and children slaughtered in his beloved adopted hometown of Hebron.

Yardena Schwartz has taken David’s letters and diary, given to her by Suzie’s daughter Jill Notowich, as the springboard for an astonishing work of history. The first third or so of “Ghosts of a Holy War” centers on the pogrom in Hebron — an event that seemed to express the limits of human barbarity, until it was eclipsed by later horrors against the Jews. So much of what unfolded in Hebron will remind the reader of Oct. 7 — beginning with the certainty of so many Jews that since they believed in peace, no harm would come to them.

“Nonsense!” said Eliezer Dan Slonim, one of Jewish Hebron’s leaders, after two women reported having overheard Arabs in the marketplace laughing about the terrible things they would do to Jews on the coming Saturday.

One of the most heartrending aspects of that Black Sabbath, Aug. 24, 1929, is the shocked sense of betrayal expressed by so many of its victims. “Have mercy on us,” pleaded Yitzhak Abushdid, a tailor, when rioters chanting “Slaughter the Jews” stormed into his home. He had made clothes for many of them. “Aren’t you our friends?” The mob strangled him with a rope and ran a sword through his father.

Meanwhile the British police and governing authorities did virtually nothing. When the mob began its rampage and Jews appealed to the police chief, he yelled at them to go in their homes, saying, “You Jews are to blame for all of this.” Arab policemen joined the bloodletting. Only after many hours, when the pogromists threatened to kill the police chief too, did he order his policemen to fetch their guns from the station. The slaughter ended moments after police opened fire — too late for Hebron’s Jews.

There is an eerie similarity about atrocities carried out against Jews in different times and places. The weapons and techniques become more sophisticated, culminating in the Nazis’ industrialized mass murder, but the spirit is always the same. Leon Trotsky described early 20th-century Russian pogromists rushing through a town, “drunk on vodka and the smell of blood,” each man ecstatic to discover that “there exist no tortures” at which he need stop. The same joy in evil was present in Hebron. One of many evocative photographs in Schwartz’s book captures it: The mob on Aug. 24, at its center a man in traditional Arab dress brandishing what looks like a long scimitar. He is exultant, arms upraised. It’s the same glee we saw over Hamas’ GoPro footage in 2023, as the terrorists machine-gunned cars containing children to the droning chant “Allahu Akhbar.” We’ve seen something of this intoxication across the West, that thrill at “the smell of blood,” by would-be pogromists enthusing “Long live Oct. 7.”

But of course there are important differences between Hebron 1929 and southern Israel 2023, most essentially that there is now a Jewish state pledged to safeguard its people’s lives. Another is that for all the horror of Hebron’s Black Sabbath, at least 250 Jews were rescued that day by their Arab neighbors, many at risk to their lives. Schwartz honors these Arabs, such as an elderly man, Abdul Shaker Amer, who guarded a home containing a rabbi, his children and a dozen other Jews. Abu Shaker dared the rioters: “Kill me! The rabbi’s family is inside, and they’re my family too.” All survived. Such stories provide a small measure of hope for humanity.

Sadly, similar accounts have not reached us from Oct. 7. The descendants of Arabs who saved Jews in 1929 must hide this fact from other Palestinians today, or be condemned as traitors. The three pogromists who were hanged by the British for their crimes, on the other hand, are honored to this day as martyrs.

Schwartz remarks that “If Arab leaders had hoped to weaken the threat of Zionism, the riots of 1929 had the opposite effect, accelerating the very process they wished to forestall.” The British responded to the pogroms throughout Palestine with classic victim-blaming, claiming the Jewish community provoked the Arabs with their (peaceful) demonstration at the Western Wall. A few years later, in 1936, the Arab High Command, a group of Arab leaders headed by al-Husseini, called for a general strike and boycott of Jewish products to protest Jewish immigration into Palestine. This protest soon escalated into violence, the Arab Revolt of 1936-39. In response, the British enacted increasingly strict restrictions on Jewish immigration into Palestine — this as the Nazis were becoming a graver threat.

“This was the moment,” Schwartz writes, “when many Zionists became militaristic in their efforts to establish a Jewish state. The seeds of the Jewish rebellion against the British that ultimately ended the British Mandate were planted here, in the aftermath of the Hebron massacre.”

I’ve been to Hebron. I was struck by its stillness, so much in contrast to the rancorous militarized zone I was expecting. I visited its museum, where I learned about the pogrom. I met the settlers (a few of them anyway), and found decent, good-humored human beings. They were devout, dedicated to maintaining a Jewish presence in Judaism’s second-holiest city, and, from what I can tell, wanted to live in peace with their Palestinian neighbors — but had a machine gun ready in the living room, just in case. I left Hebron not knowing what an answer for it might be, but thinking I understood why the settlers feel the way they do.

Schwartz’s book has deepened that sense, while adding layers of necessary, but often vexing, complexity. She handles one of the thorniest issues faced by today’s Zionist — the settlement movement — with honesty and nuance. On the one hand, she provides a pointed counternarrative to critics who claim that Israel has been hellbent throughout history on taking over Palestinian land. In fact, the reader learns, far from rushing in to settle the lands won in 1967, Israel tried to conciliate the Palestinians by staying out. They hoped that if they turned over these territories, the Palestinians would in return grant peace. Moshe Dayan told the BBC, “We’re waiting for a phone call from the Arabs” — the one that would finally end the conflict.

As a result there were zero Jews in Hebron, the burial place of Abraham and Sarah, for 12 years after 1967. Eventually religious Zionists impatient to return to the city might be forgiven for feeling that Moshiach was likely to arrive before peace with the Palestinians did. In 1979 they took matters into their own hands, sending a brigade of women and children into an abandoned Hebron building — one targeted in the 1929 massacre. The government was forced to decide whether to forcibly evict Jewish women and children from a place steeped in such history, and unsurprisingly, didn’t have the stomach for it. Hebron’s settlement community was born.

So that’s on the one hand. On the other, Schwartz writes about visiting a Palestinian — the descendant of an Arab who saved Jews in 1929 — on the Palestinian side of Hebron. She sees Israeli police impose seemingly arbitrary rules that make Palestinian lives harder, sees and hears about provocative behavior by settlers. During a festival for Shabbat Chayei Sarah, she sees marching Jewish teenagers give Palestinians the finger and vandalize their cars. When she confronts the teenagers, they look at her as if she’s crazy. “They’re killing us, and you worry about their cars?”

Which brings us back the other, first, hand: The current mayor of Hebron, Tayseer Abu Sneineh, who Schwartz interviewed for the book, was convicted of murdering unarmed Jews in 1980. (A spoiler of the interview: He isn’t sorry.)

Schwartz doesn’t claim to know what the answer is, but pans out to provide a full, lucid account of the entire Arab-Israeli conflict. Do not think, as I did at first, that this book is “about Hebron,” or one bloody episode in the Jewish people’s history. It is an overview to it all, from British Mandate Palestine to the massacres of Oct. 7.

The reader gets an appreciation of how much of this blighted history can be laid at the feet of one especially malevolent man, Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Husseini. The British elevated him to his position of enormous power after he incited riots in 1920, and decided to keep him there despite his central role in the pogroms of 1929. He was the man who ensured that the 1937 partition plan proposed by the Peel Commission would fail: Although many Arab leaders supported the plan, the mufti rejected it and threatened to have any Arab who supported it assassinated as a traitor. Any possibility that a two-state solution might be peacefully accepted vanished.

The reader also learns about the close, mutually respectful relationship between the mufti and Adolf Hitler. The mufti lived comfortably from 1941-45 in Berlin, where he was a fixture of the Nazi propaganda machine and may have been one of the most lavishly paid men on the Nazi payroll. In these days when every political opponent is deemed to be just like Hitler, it bears emphasizing: the godfather of Palestinian nationalism was literally a Hitler-lover.

The animating spirit of the defeated Reich lived again on Oct. 7. And in echoes of Hebron, Jews who got along well with Arabs were the main victims. The Jews who perished on that day were peace-lovers who drove Palestinians to doctors’ appointments, Jews who only wanted to dance at a music festival dedicated to peace. No matter how much you’ve read about Oct. 7, I defy you not to cry when you read Schwartz’ chapters about that terrible day and its aftermath.

Schwartz writes with clear, luminous prose, demonstrating the sense of timing and drama of a novelist. Much as you might wish that much of what you read were fiction, you will be glad to gain from this book a better sense of the bloody road to Oct. 7.

Kathleen Hayes is the author of ”Antisemitism and the Left: A Memoir.”

Did you enjoy this article?

You'll love our roundtable.

Editor's Picks

Israel and the Internet Wars – A Professional Social Media Review

The Invisible Student: A Tale of Homelessness at UCLA and USC

What Ever Happened to the LA Times?

Who Are the Jews On Joe Biden’s Cabinet?

You’re Not a Bad Jewish Mom If Your Kid Wants Santa Claus to Come to Your House

No Labels: The Group Fighting for the Political Center

Latest Articles

The Pope’s Kayak—A Lesson for the Jews

Sephardic Film Festival Gala, TEBH Charity Poker Tournament

Rabbis of LA | At K.I., Bringing a Stricken Community Back

A Bisl Torah — Evolving Purpose

Isaac the Invisible

Russ & Daughters Share 100 Years of Food and Culture in New Cookbook

Cornell Graduate Student Union Advancing a BDS Referendum Calling for “Armed Resistance”

From November 21 to 25, the Cornell Graduate Student Union is advancing a BDS referendum to a full vote and demanding the union refuse research grants and collaboration with institutions tied to the U.S. or Israeli militaries.

The Union Behind California’s Ethnic Studies Antisemitism Problem

Generations – A poem for Parsha Toldot

I think we met in Rebecca’s womb.

Confronting the “Supervirus of Resentment”: Jewish Wisdom Strikes Back at Tikvah Conference

The contrast between the Jewish wisdom on display at the Tikvah conference and the screaming hatefest in front of the synagogue was instructive for anyone interested in building the Jewish future.

Print Issue: Jonah Platt Is Being Jewish | November 21, 2025

In his new podcast, Jonah Platt takes on taboo topics and engages with diverse voices to see if we have any common ground left to share.

A Moment in Time: “Bookmarks”

Yiddish Sweetness of Sid Caesar

A Stark Reminder of History’s Unanswered Questions

Director and screenwriter James Vanderbilt’s film is based on the 2013 book “The Nazi and the Psychiatrist” by Jack El-Hai.

Filmmakers Gather to Advocate For Better Jewish Portrayals in Media

Jew in the City’s new Hollywood Bureau of the Jewish Institute for Television & Cinema and Marcus Freed’s Jewish Filmmakers Network partner to challenge stereotypes and create accurate representation.

Sweet Thanksgiving Treats

A Thanksgiving Feast is carbs galore. Sweetness is another hallmark of this holiday meal. The only thing that’s better is when both are mixed together.

Plant-Based Thanksgiving Recipes

Thanksgiving is about more than just the food — it’s about spending time with your loved ones.

Citrus Blossoms: An Orange Olive Oil Cake

This moist, tender cake perfectly balances fresh orange essence with the earthy notes of extra virgin olive oil.

The Festive Flavor of Roasted Chestnuts and Turkey Breast

Chestnuts are really the unsung ingredient of festive holiday fare. We hope you enjoy this incredible recipe for golden turkey breast with potatoes and chestnuts.

Table for Five: Toldot

Lentil Stew vs. Birthright

Can We Have Productive Conversations on Being Jewish? Jonah Platt on Doing His Part

Platt’s “Being Jewish” podcast brings him face to face with conservatives, progressives, activists, actors and his own family, to see if there is any ground left to share on the most taboo topics about Judaism and Israel. Especially in a world that rewards division.

Dan Raskin: Manny’s Deli, Old-School Food and Noodle Kugel

Taste Buds with Deb – Episode 133

Speech by Richard Sandler at the Milken Community School Groundbreaking

Here at the Milken Community School, we are educating young Jews who know Torah. They know who they are and where they come from. They know we are one people and they are proud to be Jews.

Milken School Holds Milestone Groundbreaking at New Campus

The Rodan Family Academic Center, according to Milken leadership, “will be a hub of learning, identity and connection for generations of Milken students.”

Rosner’s Domain | Is Israel Becoming More Religious?

When the public wants quiet and diplomats crave closure, the temptation is to pretend a problem has been managed when it has only been deferred.

What If We Listened to Each Other Like Our Future Depends on It?

If we want a city and a world where our differences don’t divide us, we have to build it — one honest conversation at a time.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.