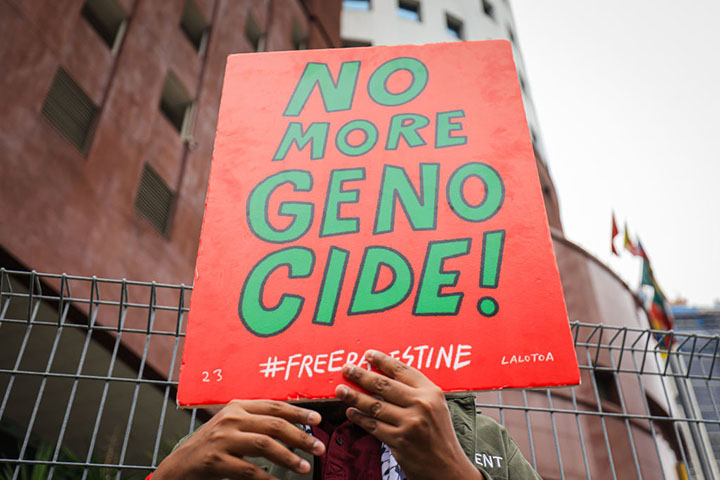

Justice of every variety—racial, social, economic, environmental—has been on many people’s minds. This has been especially true for progressives—for whom Black Lives Matter (BLM) was so urgent a cause, even a pandemic could not compel them to shelter at home.

Throughout the summer of 2020, protests, many without masks, took place in cities across America. Most were peaceful; some were violent and accompanied by looting. All seemed focused on the disparate treatment that many felt African Americans experience when they come in contact with law enforcement—whether in the form of chokings, shootings, or unjustified harassment. “No Justice, No Peace,” became the favorite rallying cry. But the coronavirus was a secondary consideration. And the volume of protestors—both in their presence and the noise they created—was dense enough that social distancing protocols were pointless. Fevers ran high, fires raged, and the heat, this time, was on the police itself.

Jews, of course, participated in these marches and the conversation about racial justice. That is no surprise. As far back as the creation of the NAACP and its Legal Defense Fund, Jews have championed the cause of racial equality. Jewish liberals have consistently shown themselves to be equal opportunity social activists, signing petitions, assembling in front of city halls, and marching alongside their brothers with raised fists. But the Jewish community’s track record of marching on behalf of fellow Jews who may be in similar, if not worse, peril . . . not so much.

American Jews have long resisted making a fuss when it came to rescuing their own people. The Holocaust is perhaps the most extreme example. Many Jewish leaders didn’t dare demand that President Franklin Roosevelt dedicate a part of the war effort to rescuing European Jewry. Even today, far too many Holocaust survivors face privations without proper support from Jewish communal organizations.

Sure, there is the occasional act of solidarity, such as the Celebrate Israel Day Parade in New York City. But that annual event probably draws an entirely different gathering of Jews from those who marched behind the Black Lives Matter banner. After all, many leaders of BLM have repeatedly invoked anti-Zionist rhetoric. Having full knowledge of this conflict, some of the Jews marching for George Floyd may have decided that the righteousness of BLM’s cause is more important than defending the safety and very existence of a Jewish homeland.

Of course, there are those who reject the organization behind the slogan “Black Lives Matter” precisely because of the anti-Zionist pronouncements of the movement’s leaders. For these people, their participation in the protests is qualified. But that’s the problem when a large mass of people gather for a united cause: a solitary statement is made, and all who are present are making it. There is no way to be exempt from the whole.

Yes, a segment of American Jewry participated in the crusade to free Soviet Jewry throughout the 1960s and 1970s. But there, too, I wonder how much overlap there was with Jews who linked arms and marched for racial justice in Selma and Montgomery, Alabama. Put simply: when it comes to putting their feet to social activism, Jews accumulate far fewer blisters marching on behalf of Jews.

When it comes to putting their feet to social activism, Jews accumulate far fewer blisters marching on behalf of Jews.

So if there is any remaining legroom and capacity to take on an additional cause, Jews should consider whether they can be of some assistance to strangers who just happen to be Jewish. French Jewry, for example, could surely benefit from some Franco-American Jewish love. France, which is home to the largest community of Jews in Europe, has witnessed roughly 15 years of virulent, often murderous, anti-Semitic misery. Most American Jews probably don’t know; even less might care: rabbis, for instance, are not pounding their pulpits on behalf of French Jews in the same way they sermonize about racial injustice. And the Jewish media, generally, has not made the story a front-page headline.

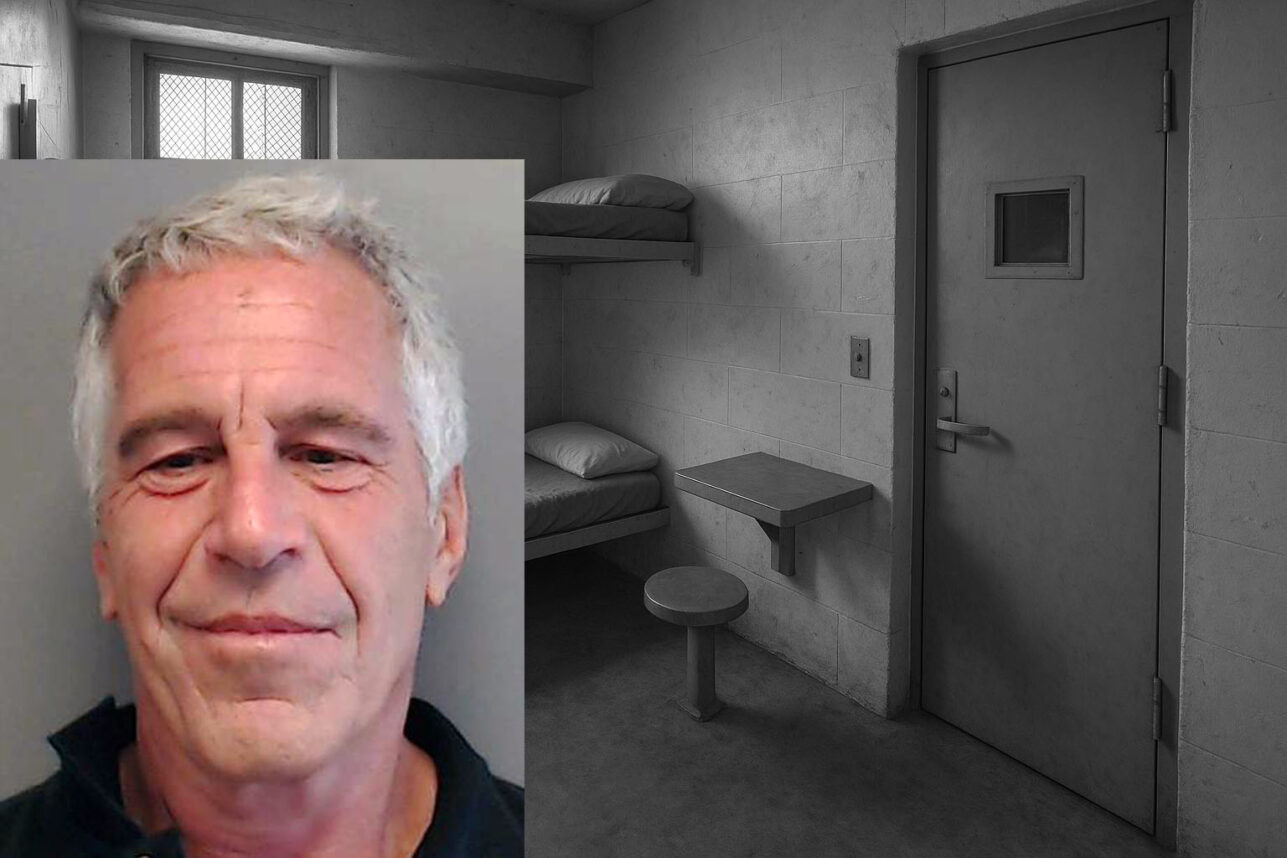

Justice in America may be flawed when it comes to arresting African Americans. But in France, which has failed to protect Jews, justice appears to be nonexistent. Take the case of Sarah Halimi, a French Jew who, in April 2017, was beaten to death and then thrown from her balcony window by an assailant (who shouted “Allahu Akbar” during the attack). In December 2019, a judge ruled that even though the assailant had a clear anti-Semitic motive for his actions, he was not criminally responsible because he perpetrated the act while under the influence of marijuana. Less than two weeks ago, a paltry 50 people protested the appeals court’s decision, a stark contrast from when the decision was first announced—thousands had expressed their outrage. Clearly, this issue does not have the same legs as the BLM crusade. Jewish lives in France haven’t mattered for years, which accounts for why tens of thousands have decamped for Israel during this recent rise in anti-Semitic violence.

The list of crimes against French Jewry, committed mainly by Muslims, is long. Twelve Jews have been murdered in France from six separate incidents since 2003. Scores have been beaten. In 2006, for example, Ilan Halimi was kidnapped by a self-described “Gang of Barbarians” and tortured for three weeks. He was discovered naked and torched. In March 2012, a gunman murdered a teacher and three students at a Jewish day school in Toulouse. Four Jews lost their lives in the terrorist attack at the kosher market in January 2015. A young man had his finger sawed off in 2017. And in March 2018, an elderly Jewish woman, Mireille Knoll, was stabbed eleven times in her apartment and burned to death. Her killers, who acknowledged that she was targeted for being Jewish, are still awaiting trial.

Certainly, anti-Semitic violence is not confined to Europe. The murder of 11 Jews at the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburg in October 2018, the shootings at the Poway Synagogue in April 2019, and the attacks against Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn, Monsey, and Jersey City in December 2019, were tragic and disturbing. But the vulnerability of Jews to such anti-Semitic violence has never been a global priority. That is because Jews are now perceived as members of the ruling class, undeserving of the paternalistic, anti-colonialist outrage routinely generated on behalf of people of color. And with Israel as a convenient piñata for anti-Semites, the persecution of the Jewish people garners even less sympathy.

Inclusiveness within the wide net of vulnerable minorities never seems to include Jews. Yet, the unwillingness of the Jewish community to galvanize support for each other is a separate matter. Why is it that Sarah Halimi’s murder does not muster the same indignation as that of George Floyd? And, more gravely, what does it say when Jews can’t muster the same compassion and sense of urgency for their own people?

Of course, it is commendable, and not surprising, that Jews can be counted on to support progressive causes. After all, many Jews express their Judaism not through Torah study but social activism. Tikkun olam has become a catchphrase that, for many, absolves the turpitude of eating shellfish so long as Jews perform good deeds. But there is no requirement that social activism extend only to the doors of strangers.

The entire world seems to be on fire. The bucket brigade, however, doesn’t move only in one direction. To those who were previously unaware of the horrific anti-Semitism in France but have been beating their breasts alongside BLM protestors: it’s time to consider saving a little passion for the plight of your own.

Thane Rosenbaum is a novelist, essayist, law professor and Distinguished University Professor at Touro College, where he directs the Forum on Life, Culture & Society. He is the legal analyst for CBS News Radio. His most recent book is titled “Saving Free Speech … From Itself.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.