For years there has been speculation regarding the kashrut of practicing yoga. Jews are either doing yoga openly, knowing that it is for their health, or quietly, unsure if they are doing something wrong. But there has never been a meeting of the Rabanim concerning yoga, and whether it is permissible for Jews to practice. Perhaps now is the right moment to lay out a bit of history and facts about yoga, and some applicable halacha (Jewish law).

Audi Gozlan

Yoga has exploded in popularity, offering guidance for improving our breath and well-being through meditation, fitness and relaxation. A multi-million-dollar industry with centers all over the world, according to yogaearth.com, approximately 300 million people regularly practice yoga and more than 36 million of them in America alone. It is also projected that 34% of people living in the U.S. who have never tried yoga will probably do so within the next year. It would not be an exaggeration to estimate that of these numbers a few million are Jews.

The recognition of yoga continues to rise as its health benefits have become more accepted and mainstream among doctors and health professionals in the U.S. The New York Times relays that 93% of integrative medical centers in America now offer yoga as a form of therapy.

In Israel, yoga first appeared shortly following the creation of the state in 1948. Prime Minister David Ben Gurion, known for practicing yoga, was frequently photographed doing headstands in public. His teacher/guru was Moshe Feldenkrais (1904-1984), developer of the Feldenkrais method—an exercise therapy that helps us reconnect to our bodies. Yoga has become widespread throughout Israel, especially in the last 20 years. According to employees of yoga.co.il, there are currently over 500,000 students and 3000 registered yoga teachers in Israel.

What is it about yoga that has attracted so many people, particularly Jews?

It is no doubt due to its benefits. Yoga provides many mental and physical health benefits, improving breath, strength, flexibility, balance and concentration. Being the ancient people of the Bible, perhaps many Jews are also able to appreciate yoga’s health benefits through this lens.

In Genesis 25 we read that following the passing of Sarah, Abraham married Ketura, who bore him six sons: Zimran, Yokshan, Madan, Midan, Yishbak and Shuach. He eventually sent these six sons to the “Land of the East,” the biblical reference to India, with precious gifts of mystical secrets related to the cosmos of creation. The commentator Rashi explains that among these gifts were the healing powers to overcome tumas, the Hindu word for “darkness.”

According to 15th-century Kabbalist Menashe Ben Israel in his book “Nishmat Chayim” (“Living Soul”), the sons were initially known in India as Abrahmans, the children of the famous Abraham. As they integrated into this new land, they became known as the Brahmans, important priests, spreading the teachings of their father throughout India, where Abraham became known as Brahma, and his wife Sarah as Sarahsvati.

It is said that sometime in the 18th century BCE, Abraham authored the first text of the Kabbalah, “Sefer Yetsirah,” or “The Book of Shapes.” Incidentally, this is the same period in which the Vedas were being written by the children of Brahma in India.

What is yoga?

Historically, the word “yoga” comes from the Sanskrit root “yuj,” and is mentioned for the first time in the ancient Hindu Rig Vedas. Dating back to the same time period as Abraham and probably inspired by his teachings on creation, the Brahmans composed the ancient Vedas (“knowledge” in Sanskrit and Hebrew), where yoga, “to bond,” is mentioned.

At its origin, yoga was meant to bring harmony, stillness and unity with the inner self by breathing in certain patterns that stimulate more awareness. It does not refer to any deity or form of worship. It simply means to connect to your higher inner self, by looking inward beyond the layers of life.

In ancient times, yoga was taught through meditation, solitude and detachment from the world to reach enlightenment. We become in tune with our mind and body’s thoughts and feelings through breath work, concentration, and meditation practices. This teaching has existed for thousands of years, while the development of poses in yoga only began in the 1900s. It is the yoga postures that have attracted millions of people over the last century.

Does yoga present a Halachic problem?

Yoga is a science, not a religion. It was created by Hindus who taught this discipline of postures to improve our health and well-being. Like yoga, karate and kung fu are also sciences of movement, concentration and breath, developed by 17th-century East Asian Buddhist teachers.

The core halachic question is this: Do yoga postures have a purpose? If yes, they do not fall within the halachic prohibitions of Avodah Zarah and Chukat Akum.

Let’s look atthese concepts of Jewish law.

Avodah zarah, idol worship, is directly contrary to Judaism, as it specifically denounces our faith in the one G-d. “Idol worship” means that one cannot participate in any idolatrous practices, not even mentioning the names of deities if said with them in mind. “Honouring” any force is avodahzarah, as is any intention regarding idol worship, even without action (Exodus 20:3-5, Deuteronomy 5:7-9; see also Exodus 23:13 Leviticus 19:4, Deuteronomy 7:25-26, 17:2-5).

Chukat Akum is the proscription that Jews must not be like gentiles in style and practice. In the words of the Torah, “You shall not follow gentile customs” (Leviticus 20:23). Commentator Tosfot in the Talmud, Avodah Zarah (11A) explains that there are two types of Chukat Akum:

1. Doing things that normally serve a purpose, but for the idol.

2. Doing things for the idol worship that do not make sense and serve no purpose.

According to the view of the Maharik, if a Jew participates in a gentile ritual that has no purpose, they are likely doing it in order to be similar to idol worshipers.

Rabbi Aharon Felder, a student of Rav Moshe Feinstein (the famous rabbinical judge who died in 1986), records in his memoir “Rishumei Ahron” that he once asked the Rav about whether yoga was halachically kosher. Rabbi Felder said the Rav told him that yoga is not idolatry. If anything, yoga was only a mental preparation for the possible worship of deities, and is therefore permissible. According to the Rav, yoga would not fall into the category of Chukat Akum since it does make sense and serves a purpose related to health.

In June 1977, when a Rabbinical tribunal in Israel ruled that meditation and yoga was avodahzarah, the Rebbe (Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson) protested the decision, saying it was possible to practice these methods in a kosher way, without Hindu rituals.

During the ’60s and ’70s, the Rebbe became aware of the many Jews traveling to the East in search of inner harmony and a spiritual awakening. He also saw yoga’s major influence on the West, and how in some cases it was being packaged along with Hindu rituals unnecessary to the practice of yoga.

To the surprise of many, and in contrast to his rabbinical contemporaries, the Rebbe never closed the door to healing through meditation or yoga simply because of its attachment to India.

To the surprise of many, and in contrast to his rabbinical contemporaries, the Rebbe never closed the door to healing through meditation or yoga simply because of its attachment to India. On the contrary he was probably its most vocal proponent, urging that action be taken “to research said methods with a view to perfecting them and adopting their practice on a wider scale, and offered in a ‘kosher way’” (Personal Letters, January 1978).

Unfortunately, there is a lot of misinformation about what yoga really is, and whether it is kosher or not. Unlike what some contend, “yoga” is not the name of a deity. Yoga means being connected inwardly. It is the one who practices yoga who is free to choose how to define this union. The Rebbe himself used the word “yoga” in the letters he wrote during the late 1970s.

We do not see Hindus flocking to yoga centers to do postures for deities the same way they crowd at temples for rituals, chanting, mantras and prayers. Even from a fitness perspective, most Hindus do not practice yoga as exercise. Yoga has gained ground in India in the last few decades thanks in large part to the West.

Dr. Mark Singleton, an Iyengar yoga teacher and scholar, has published various books and articles on the origins of yoga. In 2010, he released a new book, “Yoga Body—The Origins of Modern Posture Practice” (Oxford University Press 2010) in which he proves, through years of extensive research, that the postures did not exist thousands of years ago.

Aside from a few seated poses, no historical evidence exists that people in ancient India practiced the yoga poses that are now taught all over the world. They are not ancestral Hindu rituals, they are not 5000 years old, and there are no references to these poses in any of the ancient Hindu texts.

The oldest text displaying the first yoga poses are found in a manuscript entitled “Sritattvanidhi,” compiled in the early 1800s by Mummadi Krishnaraja, a ruler in Mysore, India. In this treatise, Krishnaraja demonstrates 122 postures in a chapter, including back-bends and handstands, for exercise purposes. Interestingly, he also shares poses originating from gymnasts in India, like push-ups and push down chaturanga dandasana, which eventually became part of the Sun Salutations.

Assembled by individual Indian athletes, gymnasts and bodybuilders fewer than 200 years ago, the purpose of creating the first yoga postures was to inspire people to get fit and stay in good shape.

Tirumalei Krishnamacharya, a yoga teacher, ayurvedic healer and scholar of the early 1900s, is considered the father of modern yoga. He was a major contributor to the physical culture of India, influencing the creation of yoga postures and even adding poses from British gymnastics. His world-famous students B.K.S. Iyengar and Pattabhi Jois formulated their own techniques of yoga and physical development of the poses based on the “Sritattvanidhi,” both incorporating further gymnastic postures and props into the practice. As Singleton explains that according to Iyengar, from a deeper view the spiritual path of yoga stems from the “Yoga Sutra,” “Baghvad Gita,” and “Upanishads.” Yet this is a uniquely philosophical view, as the yoga postures did not exist until Krishnamacharya in the 1900s.

Do the Hindu names of the poses refer to deities?

Although most of the yoga postures have Sanskrit names, they do not refer to Hindu deities, except for the Warrior II, Virabhadrasana in Sanskrit. The names of the postures came mostly from the first yoga teachers mentioned above, who chose them through creative insight into animals, people and things in nature.

Richard Rosen, a well-known yoga teacher, scholar and author from Oakland, California explains the origins of yoga poses and their names based on his many years of research. Like Singleton, Rosen writes that history shows the yoga postures are not an ancient tradition, and that the names of the poses only began to appear in yoga books written in the 20th century.

Therefore, the yoga poses cannot be avodah zarah, as they were never an ancestral Hindu practice. Nor is yoga a problem of chukat akum, since the poses were never meant to be a means to serve idols. Rather, yoga has a physical and mental purpose proven to be beneficial for our health, and is therefore neither a preparation nor an action of avodah zarah.

This does not mean yoga cannot become idol worship. Like anything, the moment we infuse an intention to do something for avodah zarah, then the action becomes a problem.

This does not mean yoga cannot become idol worship. Like anything, the moment we infuse an intention to do something for avodah zarah, then the action becomes a problem. This does not imply that an action we do for idol worship is prohibited, since it can be a normal thing like eating, drinking, dancing, etc. However, if we do something that doesn’t necessarily mean anything, except as a ritual or special thing to do for idols, then this is a prohibited action.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe On Yoga

One Hindu guru who caught the Rebbe’s attention was the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, founder of TM (Transcendental Meditation). At the time, a spirit of rebelliousness was sweeping over the youth of America. The Beatles, students of the guru, played a big role in spreading yoga-infused with Eastern teachings across the U.S. Radical fads, new music and pop culture emerged from the east. Hinduism and TM became widespread.

The Rebbe was clear about what was contrary to Judaism in these teachings, but he also recognized the positive elements that could be practiced in a kosher way. The Rebbe believed that meditation and yoga could be very useful if practiced strictly as a healing technique, without any Hindu rituals, as we read in letters between him and Dr. Yehudah Landes:

“It follows that if these therapeutic methods, insofar as they are utterly devoid of any ritual implications … many could benefit from such treatment … This is a matter of healing of the highest order, since it has to do with the mind. It would therefore be wrong to deny such treatment to those who need it … if they had a choice of getting it the kosher way” (January 1978).

The Rebbe wanted to share his vision, but initially decided to keep who he spoke with and what was said confidential, as “the subject matter was of a sensitive nature,” and his view might be used “to encourage that which it seeks to discourage and preclude, namely involvement in Eastern cults.”

At first, he spoke only with certain individuals he felt could further his plan. “I am asking you to use all discretion … as to its source and its utilization … I must however, point out with all due emphasis that in my opinion the problem has reached such proportions that time is extremely important” (March 1978). The Rebbe saw the positive effects of meditation and yoga, but maintained discretion so that his views would not be interpreted as supportive of the Gurus establishing ashrams on American soil at that time.

Before making the Rebbe’s point of view public, a well-considered plan had to be devised. Strongly committed to establishing a program, the Rebbe promised to those initially involved that “on my part, I will do all I can to mobilize all possible cooperation on behalf of this cause which, I strongly believe, should be pursued with the utmost vigor” (March 1978).

One person chosen by the Rebbe to initiate this task was Dr. Yehudah Landes. A clinical psychologist knowledgeable on the subject of Eastern philosophies, especially that of TM, Dr. Landes was among the few key people with whom the Rebbe spoke freely about yoga, meditation and the Maharishi. In the late 1970s they began to develop a plan to which the Rebbe committed as a partner and financial investor, telling Dr. Landes in March 1978 that “if in the first stage of implementing the program there would be need for funding the initial outlay, my secretariat would make such funds available.”

The outline devised by Dr. Landes and the Rebbe consisted of the following:

A center inspired by Halachic and Chasidic but non-religious orientation for meditation, breathing and posture exercises open to Jews and non-Jews.

Chanting nigunim (melodies).

Holistic workshops for achieving well being.

Peer discussions to help people open up.

A kosher kitchen.

In June 1979 the Rebbe held a farbrengen, a gathering where he spoke about meditation and how it could bring menuchat hanefesh, peace within the heart, and chizuk haberiut, strengthening of the health, if only it could be taught in a kosher way. This was a historic moment in Lubavitch, the significance of which we can only truly appreciate today.

The Rebbe envisioned a big project that would be promoted across the American media. In the Rebbe’s own words, “all due publicity should be given about the availability of such methods” (January 1978). The Rebbe saw into the future and recognized the impact that Eastern teachings would have, particularly upon Jews. Even if most Rabonim maintained that yoga and meditation could not be made kosher, still the Rebbe was optimistic, knowing that yoga was not dependent on religion and that, especially since there was a great number of Jews involved, “the vital importance and urgency of saving so many souls from avodah zarah not only warrants but dictates every possible effort.”

The Rebbe understood that “if these therapeutic methods could be practiced without any rites and rituals, they would have two positive effects: First, they would heal those who need such therapies. Second, if they had a choice of getting such treatments in a kosher way, these people would not expose themselves to avodah zarah.” He maintained that the idolatrous elements in said movements were “not germane, indeed non-essential, to the therapy itself” (March 1978).

What is surprising, is that after all the instructions from the Rebbe, there is still doubt as to whether yoga can be done in a kosher way. I had the privilege of being given these letters between the Rebbe and Dr. Landes from a spiritual mentor in the early 2000s, when Rabbi Laibel Groner, the Rebbe’s personal secretary, was at my home for a gathering, with instructions to use them wisely. At the time, I was finishing my first book about kosher meditation, “Gifts of Abraham” (Ogo Books, 2002), and had begun working on a kosher system of yoga.

After reading the letters, I was blown away at how the Rebbe spoke over forty years ago but was talking to us now. Hoping to call Dr. Landes to have a frank discussion, I discovered through Rabbi Groner that he had unfortunately passed away, and so I decided to call his wife to offer my condolences. When I brought up the letters exchanged between the Rebbe and her husband she was amazed, remembering those discussions well. When I asked her why no action had taken place with all the blessings of the Rebbe, she said, with a sigh, “My husband did not have support in the community to advance such a project.”

It is time to finally let go of the misinformation that yoga is avodah zarah. Having origins in India does not make it idol worship. Jews have adopted many things from the nations, serving practical purposes in a kosher way, including sciences, design and sports. Why not yoga? Meant and used for health and fitness, there is simply no reason to call yoga a religious activity.

The real question is not whether yoga is kosher, but whether the yoga you are practicing is kosher.

The real question is not whether yoga is kosher, but whether the yoga you are practicing is kosher.

How to Keep Yoga Kosher

The Jewish community should be encouraged to organize kosher yoga classes by hiring qualified teachers.

Before taking a class, make sure to choose one that teaches yoga poses as fitness. If the school also teaches about other religions through chants, mantras and philosophies, then there will be issues with halacha. Usually, yoga taught at gyms, hot yoga studios and the Ys are fine, as long as they are only teaching about the postures, their alignment and breath work.

Intention is vital. Practice yoga as physical stretches and exercises for your well-being, in order to heal and have more awareness in your mind and body. Your intention should always be about G-d and how He gave you this body filled with breath.

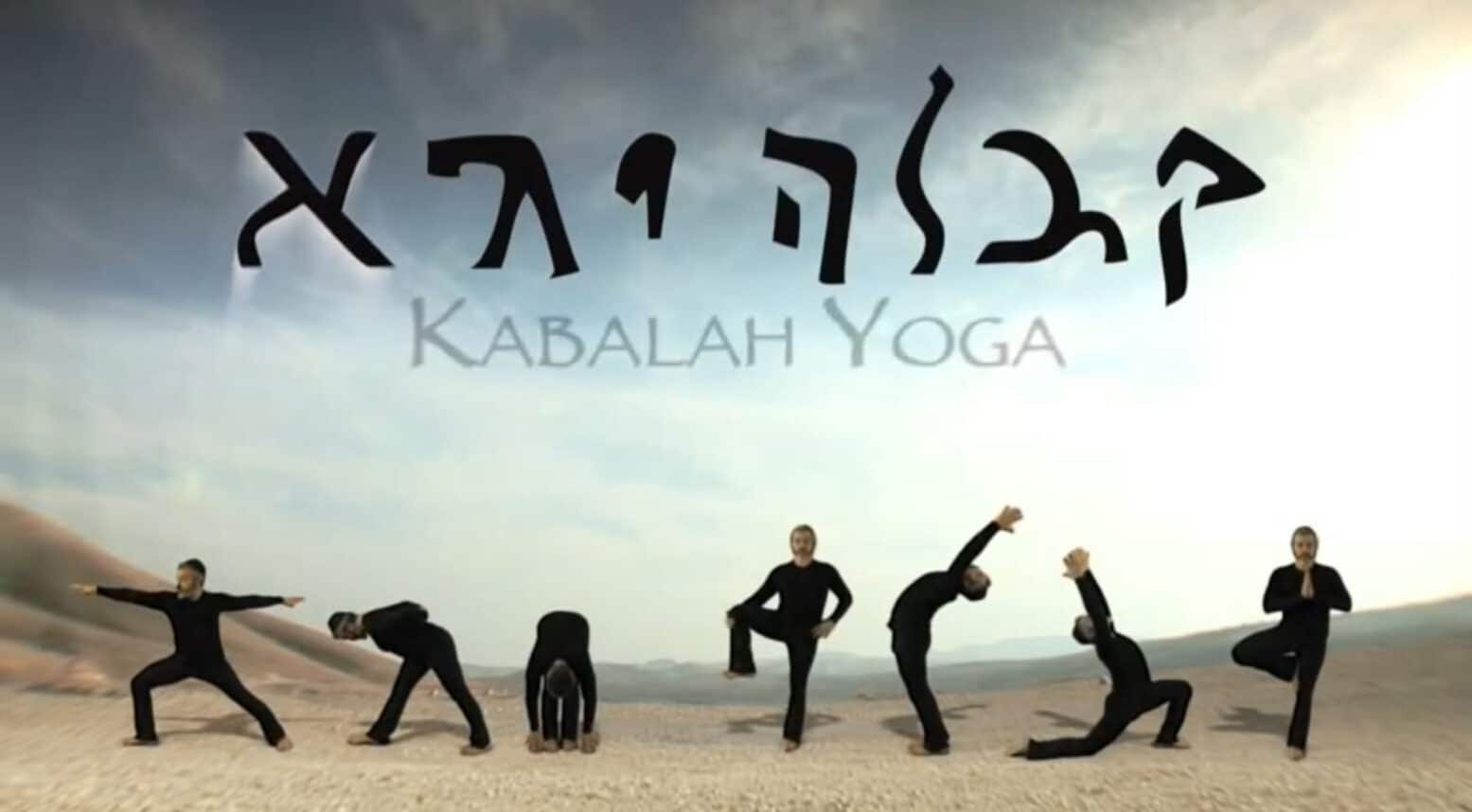

I take the Rebbe’s letters addressed to Dr. Landes personally, since my name is also Yehuda, and they came to me in a wondrous way. I was inspired to develop a kosher system of meditation and yoga called “Kabalah Yoga,” based on a series of stretches and exercises that take the shapes of the Hebrew letters. I am grateful that the system is available through videos, workshops and a book I released with New Harbinger in 2017. People from all walks of life are learning how to stretch their bodies into the poses of the Alef Beit.

It is in our interest to be healthy, to know our breath, and live with awareness, helping connect.

The advantage of stretching the body is that it forces you to observe your breath, to find alignment and connection to everypart of your body. It is in our interest to be healthy, to know our breath, and live with awareness, helping connect us to G-d more deeply. It is also a mitzvah (commandment) tocare for our physical body, as it is written in the Torah: “Take heed to yourself and take care of your lives,” and, “You shall guard and preserve your body” (Deuteronomy 4:9, 4:15).

Rambam explains exercise as either “vigorous or gentle movement, or a combination of the two, in order to improve our breathing” (Kuntras Hanhagat HaBriut 1:3). As the Rebbe once explained, the more we are in tune with our breath, the external layer of the soul, the further we awaken in us the light of breath through the nostrils, flowing our chayin, vitality, and chayin dechayin, deeper, and more creative vitality” (Torat Menachem, April 1951).

Audi Gozlan, Ph.D, is a lawyer, rabbi and yoga teacher.

“The more I was studying Judaism, especially Torah, thinking about what I would be teaching as a rabbi, the more I saw parallels between Judaism and poetry. I think Judaism is a big poem.”

Marla and Libby are back with another episode of Schmuckboys. This week the duo start with their updates of the week. Libby shares about how her and Jack are celebrating one year of marriage. And the two talk about the exciting news of having a…

He engaged with tens of thousands of college students in hundreds of campuses over more than a decade and stood tall with his coolness and his arguments. He wanted to make loving America cool again.

With the world and so many lives in turmoil this year, how best to prepare for the High Holy Days? One answer is in Pirkei Avot, “The Sayings of the Fathers.”

As I study Pirkei Avot at this time of the year, the Days of Awe hover in the background. As my inner preparation for the Days of Awe coincides with my study of Pirkei Avot, unexpected connections emerge.

How can a sophisticated modern Jew integrate the pious promises of our tradition with the tragic and often painful reality of our world and our lives? Perhaps we can use these 10 days to reflect on these timeless and timely questions.

How will a combined student body of millions of undergraduate students marinated in an antisemitic miasma on social media receive its Jewish peers this fall? If the past is any indication, we should buckle up.

Yoga Is Kosher?!

Audi Gozlan

For years there has been speculation regarding the kashrut of practicing yoga. Jews are either doing yoga openly, knowing that it is for their health, or quietly, unsure if they are doing something wrong. But there has never been a meeting of the Rabanim concerning yoga, and whether it is permissible for Jews to practice. Perhaps now is the right moment to lay out a bit of history and facts about yoga, and some applicable halacha (Jewish law).

Yoga has exploded in popularity, offering guidance for improving our breath and well-being through meditation, fitness and relaxation. A multi-million-dollar industry with centers all over the world, according to yogaearth.com, approximately 300 million people regularly practice yoga and more than 36 million of them in America alone. It is also projected that 34% of people living in the U.S. who have never tried yoga will probably do so within the next year. It would not be an exaggeration to estimate that of these numbers a few million are Jews.

The recognition of yoga continues to rise as its health benefits have become more accepted and mainstream among doctors and health professionals in the U.S. The New York Times relays that 93% of integrative medical centers in America now offer yoga as a form of therapy.

In Israel, yoga first appeared shortly following the creation of the state in 1948. Prime Minister David Ben Gurion, known for practicing yoga, was frequently photographed doing headstands in public. His teacher/guru was Moshe Feldenkrais (1904-1984), developer of the Feldenkrais method—an exercise therapy that helps us reconnect to our bodies. Yoga has become widespread throughout Israel, especially in the last 20 years. According to employees of yoga.co.il, there are currently over 500,000 students and 3000 registered yoga teachers in Israel.

What is it about yoga that has attracted so many people, particularly Jews?

It is no doubt due to its benefits. Yoga provides many mental and physical health benefits, improving breath, strength, flexibility, balance and concentration. Being the ancient people of the Bible, perhaps many Jews are also able to appreciate yoga’s health benefits through this lens.

In Genesis 25 we read that following the passing of Sarah, Abraham married Ketura, who bore him six sons: Zimran, Yokshan, Madan, Midan, Yishbak and Shuach. He eventually sent these six sons to the “Land of the East,” the biblical reference to India, with precious gifts of mystical secrets related to the cosmos of creation. The commentator Rashi explains that among these gifts were the healing powers to overcome tumas, the Hindu word for “darkness.”

According to 15th-century Kabbalist Menashe Ben Israel in his book “Nishmat Chayim” (“Living Soul”), the sons were initially known in India as Abrahmans, the children of the famous Abraham. As they integrated into this new land, they became known as the Brahmans, important priests, spreading the teachings of their father throughout India, where Abraham became known as Brahma, and his wife Sarah as Sarahsvati.

It is said that sometime in the 18th century BCE, Abraham authored the first text of the Kabbalah, “Sefer Yetsirah,” or “The Book of Shapes.” Incidentally, this is the same period in which the Vedas were being written by the children of Brahma in India.

What is yoga?

Historically, the word “yoga” comes from the Sanskrit root “yuj,” and is mentioned for the first time in the ancient Hindu Rig Vedas. Dating back to the same time period as Abraham and probably inspired by his teachings on creation, the Brahmans composed the ancient Vedas (“knowledge” in Sanskrit and Hebrew), where yoga, “to bond,” is mentioned.

At its origin, yoga was meant to bring harmony, stillness and unity with the inner self by breathing in certain patterns that stimulate more awareness. It does not refer to any deity or form of worship. It simply means to connect to your higher inner self, by looking inward beyond the layers of life.

In ancient times, yoga was taught through meditation, solitude and detachment from the world to reach enlightenment. We become in tune with our mind and body’s thoughts and feelings through breath work, concentration, and meditation practices. This teaching has existed for thousands of years, while the development of poses in yoga only began in the 1900s. It is the yoga postures that have attracted millions of people over the last century.

Does yoga present a Halachic problem?

Yoga is a science, not a religion. It was created by Hindus who taught this discipline of postures to improve our health and well-being. Like yoga, karate and kung fu are also sciences of movement, concentration and breath, developed by 17th-century East Asian Buddhist teachers.

The core halachic question is this: Do yoga postures have a purpose? If yes, they do not fall within the halachic prohibitions of Avodah Zarah and Chukat Akum.

Let’s look at these concepts of Jewish law.

Avodah zarah, idol worship, is directly contrary to Judaism, as it specifically denounces our faith in the one G-d. “Idol worship” means that one cannot participate in any idolatrous practices, not even mentioning the names of deities if said with them in mind. “Honouring” any force is avodah zarah, as is any intention regarding idol worship, even without action (Exodus 20:3-5, Deuteronomy 5:7-9; see also Exodus 23:13 Leviticus 19:4, Deuteronomy 7:25-26, 17:2-5).

Chukat Akum is the proscription that Jews must not be like gentiles in style and practice. In the words of the Torah, “You shall not follow gentile customs” (Leviticus 20:23). Commentator Tosfot in the Talmud, Avodah Zarah (11A) explains that there are two types of Chukat Akum:

1. Doing things that normally serve a purpose, but for the idol.

2. Doing things for the idol worship that do not make sense and serve no purpose.

According to the view of the Maharik, if a Jew participates in a gentile ritual that has no purpose, they are likely doing it in order to be similar to idol worshipers.

Rabbi Aharon Felder, a student of Rav Moshe Feinstein (the famous rabbinical judge who died in 1986), records in his memoir “Rishumei Ahron” that he once asked the Rav about whether yoga was halachically kosher. Rabbi Felder said the Rav told him that yoga is not idolatry. If anything, yoga was only a mental preparation for the possible worship of deities, and is therefore permissible. According to the Rav, yoga would not fall into the category of Chukat Akum since it does make sense and serves a purpose related to health.

In June 1977, when a Rabbinical tribunal in Israel ruled that meditation and yoga was avodah zarah, the Rebbe (Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson) protested the decision, saying it was possible to practice these methods in a kosher way, without Hindu rituals.

During the ’60s and ’70s, the Rebbe became aware of the many Jews traveling to the East in search of inner harmony and a spiritual awakening. He also saw yoga’s major influence on the West, and how in some cases it was being packaged along with Hindu rituals unnecessary to the practice of yoga.

To the surprise of many, and in contrast to his rabbinical contemporaries, the Rebbe never closed the door to healing through meditation or yoga simply because of its attachment to India. On the contrary he was probably its most vocal proponent, urging that action be taken “to research said methods with a view to perfecting them and adopting their practice on a wider scale, and offered in a ‘kosher way’” (Personal Letters, January 1978).

Unfortunately, there is a lot of misinformation about what yoga really is, and whether it is kosher or not. Unlike what some contend, “yoga” is not the name of a deity. Yoga means being connected inwardly. It is the one who practices yoga who is free to choose how to define this union. The Rebbe himself used the word “yoga” in the letters he wrote during the late 1970s.

We do not see Hindus flocking to yoga centers to do postures for deities the same way they crowd at temples for rituals, chanting, mantras and prayers. Even from a fitness perspective, most Hindus do not practice yoga as exercise. Yoga has gained ground in India in the last few decades thanks in large part to the West.

Dr. Mark Singleton, an Iyengar yoga teacher and scholar, has published various books and articles on the origins of yoga. In 2010, he released a new book, “Yoga Body—The Origins of Modern Posture Practice” (Oxford University Press 2010) in which he proves, through years of extensive research, that the postures did not exist thousands of years ago.

Aside from a few seated poses, no historical evidence exists that people in ancient India practiced the yoga poses that are now taught all over the world. They are not ancestral Hindu rituals, they are not 5000 years old, and there are no references to these poses in any of the ancient Hindu texts.

The oldest text displaying the first yoga poses are found in a manuscript entitled “Sritattvanidhi,” compiled in the early 1800s by Mummadi Krishnaraja, a ruler in Mysore, India. In this treatise, Krishnaraja demonstrates 122 postures in a chapter, including back-bends and handstands, for exercise purposes. Interestingly, he also shares poses originating from gymnasts in India, like push-ups and push down chaturanga dandasana, which eventually became part of the Sun Salutations.

Assembled by individual Indian athletes, gymnasts and bodybuilders fewer than 200 years ago, the purpose of creating the first yoga postures was to inspire people to get fit and stay in good shape.

Tirumalei Krishnamacharya, a yoga teacher, ayurvedic healer and scholar of the early 1900s, is considered the father of modern yoga. He was a major contributor to the physical culture of India, influencing the creation of yoga postures and even adding poses from British gymnastics. His world-famous students B.K.S. Iyengar and Pattabhi Jois formulated their own techniques of yoga and physical development of the poses based on the “Sritattvanidhi,” both incorporating further gymnastic postures and props into the practice. As Singleton explains that according to Iyengar, from a deeper view the spiritual path of yoga stems from the “Yoga Sutra,” “Baghvad Gita,” and “Upanishads.” Yet this is a uniquely philosophical view, as the yoga postures did not exist until Krishnamacharya in the 1900s.

Do the Hindu names of the poses refer to deities?

Although most of the yoga postures have Sanskrit names, they do not refer to Hindu deities, except for the Warrior II, Virabhadrasana in Sanskrit. The names of the postures came mostly from the first yoga teachers mentioned above, who chose them through creative insight into animals, people and things in nature.

Richard Rosen, a well-known yoga teacher, scholar and author from Oakland, California explains the origins of yoga poses and their names based on his many years of research. Like Singleton, Rosen writes that history shows the yoga postures are not an ancient tradition, and that the names of the poses only began to appear in yoga books written in the 20th century.

Therefore, the yoga poses cannot be avodah zarah, as they were never an ancestral Hindu practice. Nor is yoga a problem of chukat akum, since the poses were never meant to be a means to serve idols. Rather, yoga has a physical and mental purpose proven to be beneficial for our health, and is therefore neither a preparation nor an action of avodah zarah.

This does not mean yoga cannot become idol worship. Like anything, the moment we infuse an intention to do something for avodah zarah, then the action becomes a problem. This does not imply that an action we do for idol worship is prohibited, since it can be a normal thing like eating, drinking, dancing, etc. However, if we do something that doesn’t necessarily mean anything, except as a ritual or special thing to do for idols, then this is a prohibited action.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe On Yoga

One Hindu guru who caught the Rebbe’s attention was the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, founder of TM (Transcendental Meditation). At the time, a spirit of rebelliousness was sweeping over the youth of America. The Beatles, students of the guru, played a big role in spreading yoga-infused with Eastern teachings across the U.S. Radical fads, new music and pop culture emerged from the east. Hinduism and TM became widespread.

The Rebbe was clear about what was contrary to Judaism in these teachings, but he also recognized the positive elements that could be practiced in a kosher way. The Rebbe believed that meditation and yoga could be very useful if practiced strictly as a healing technique, without any Hindu rituals, as we read in letters between him and Dr. Yehudah Landes:

“It follows that if these therapeutic methods, insofar as they are utterly devoid of any ritual implications … many could benefit from such treatment … This is a matter of healing of the highest order, since it has to do with the mind. It would therefore be wrong to deny such treatment to those who need it … if they had a choice of getting it the kosher way” (January 1978).

The Rebbe wanted to share his vision, but initially decided to keep who he spoke with and what was said confidential, as “the subject matter was of a sensitive nature,” and his view might be used “to encourage that which it seeks to discourage and preclude, namely involvement in Eastern cults.”

At first, he spoke only with certain individuals he felt could further his plan. “I am asking you to use all discretion … as to its source and its utilization … I must however, point out with all due emphasis that in my opinion the problem has reached such proportions that time is extremely important” (March 1978). The Rebbe saw the positive effects of meditation and yoga, but maintained discretion so that his views would not be interpreted as supportive of the Gurus establishing ashrams on American soil at that time.

Before making the Rebbe’s point of view public, a well-considered plan had to be devised. Strongly committed to establishing a program, the Rebbe promised to those initially involved that “on my part, I will do all I can to mobilize all possible cooperation on behalf of this cause which, I strongly believe, should be pursued with the utmost vigor” (March 1978).

One person chosen by the Rebbe to initiate this task was Dr. Yehudah Landes. A clinical psychologist knowledgeable on the subject of Eastern philosophies, especially that of TM, Dr. Landes was among the few key people with whom the Rebbe spoke freely about yoga, meditation and the Maharishi. In the late 1970s they began to develop a plan to which the Rebbe committed as a partner and financial investor, telling Dr. Landes in March 1978 that “if in the first stage of implementing the program there would be need for funding the initial outlay, my secretariat would make such funds available.”

The outline devised by Dr. Landes and the Rebbe consisted of the following:

In June 1979 the Rebbe held a farbrengen, a gathering where he spoke about meditation and how it could bring menuchat hanefesh, peace within the heart, and chizuk haberiut, strengthening of the health, if only it could be taught in a kosher way. This was a historic moment in Lubavitch, the significance of which we can only truly appreciate today.

The Rebbe envisioned a big project that would be promoted across the American media. In the Rebbe’s own words, “all due publicity should be given about the availability of such methods” (January 1978). The Rebbe saw into the future and recognized the impact that Eastern teachings would have, particularly upon Jews. Even if most Rabonim maintained that yoga and meditation could not be made kosher, still the Rebbe was optimistic, knowing that yoga was not dependent on religion and that, especially since there was a great number of Jews involved, “the vital importance and urgency of saving so many souls from avodah zarah not only warrants but dictates every possible effort.”

The Rebbe understood that “if these therapeutic methods could be practiced without any rites and rituals, they would have two positive effects: First, they would heal those who need such therapies. Second, if they had a choice of getting such treatments in a kosher way, these people would not expose themselves to avodah zarah.” He maintained that the idolatrous elements in said movements were “not germane, indeed non-essential, to the therapy itself” (March 1978).

What is surprising, is that after all the instructions from the Rebbe, there is still doubt as to whether yoga can be done in a kosher way. I had the privilege of being given these letters between the Rebbe and Dr. Landes from a spiritual mentor in the early 2000s, when Rabbi Laibel Groner, the Rebbe’s personal secretary, was at my home for a gathering, with instructions to use them wisely. At the time, I was finishing my first book about kosher meditation, “Gifts of Abraham” (Ogo Books, 2002), and had begun working on a kosher system of yoga.

After reading the letters, I was blown away at how the Rebbe spoke over forty years ago but was talking to us now. Hoping to call Dr. Landes to have a frank discussion, I discovered through Rabbi Groner that he had unfortunately passed away, and so I decided to call his wife to offer my condolences. When I brought up the letters exchanged between the Rebbe and her husband she was amazed, remembering those discussions well. When I asked her why no action had taken place with all the blessings of the Rebbe, she said, with a sigh, “My husband did not have support in the community to advance such a project.”

It is time to finally let go of the misinformation that yoga is avodah zarah. Having origins in India does not make it idol worship. Jews have adopted many things from the nations, serving practical purposes in a kosher way, including sciences, design and sports. Why not yoga? Meant and used for health and fitness, there is simply no reason to call yoga a religious activity.

The real question is not whether yoga is kosher, but whether the yoga you are practicing is kosher.

How to Keep Yoga Kosher

I take the Rebbe’s letters addressed to Dr. Landes personally, since my name is also Yehuda, and they came to me in a wondrous way. I was inspired to develop a kosher system of meditation and yoga called “Kabalah Yoga,” based on a series of stretches and exercises that take the shapes of the Hebrew letters. I am grateful that the system is available through videos, workshops and a book I released with New Harbinger in 2017. People from all walks of life are learning how to stretch their bodies into the poses of the Alef Beit.

The advantage of stretching the body is that it forces you to observe your breath, to find alignment and connection to every part of your body. It is in our interest to be healthy, to know our breath, and live with awareness, helping connect us to G-d more deeply. It is also a mitzvah (commandment) to care for our physical body, as it is written in the Torah: “Take heed to yourself and take care of your lives,” and, “You shall guard and preserve your body” (Deuteronomy 4:9, 4:15).

Rambam explains exercise as either “vigorous or gentle movement, or a combination of the two, in order to improve our breathing” (Kuntras Hanhagat HaBriut 1:3). As the Rebbe once explained, the more we are in tune with our breath, the external layer of the soul, the further we awaken in us the light of breath through the nostrils, flowing our chayin, vitality, and chayin dechayin, deeper, and more creative vitality” (Torat Menachem, April 1951).

Audi Gozlan, Ph.D, is a lawyer, rabbi and yoga teacher.

Did you enjoy this article?

You'll love our roundtable.

Editor's Picks

Israel and the Internet Wars – A Professional Social Media Review

The Invisible Student: A Tale of Homelessness at UCLA and USC

What Ever Happened to the LA Times?

Who Are the Jews On Joe Biden’s Cabinet?

You’re Not a Bad Jewish Mom If Your Kid Wants Santa Claus to Come to Your House

No Labels: The Group Fighting for the Political Center

Latest Articles

Stage and Canvas: Fiddler on the Roof and the Art of David Labkovski at CSUN

Israel’s ‘Godfather’ Moment

TalkIsrael Shares Authentic and Impactful Pro-Israel Content from Gen Z

Charlie Kirk, Christian Nationalism and the Jews

‘The Boys in the Light’: Honoring a Father, the Soldiers Who Saved Him, and a Legacy of Courage

Boxes of Hope: Shaili Brings the Spirit of Rosh Hashanah to Those in Need

Rabbis of LA | How a German Poet Became an American Rabbi

“The more I was studying Judaism, especially Torah, thinking about what I would be teaching as a rabbi, the more I saw parallels between Judaism and poetry. I think Judaism is a big poem.”

Until This Day – A poem for Parsha Ki Tavo

I know what I have to do…

Hadassah Elects VP, OBKLA Anniversary, MDA Ambulance Dedication, Sharaka Delegation

Notable people and events in the Jewish LA community.

Mark Pizza and Haifa Restaurant Burglarized Again, Owners Frustrated

Bigamy, Divorce and the Fair Captive

A Bisl Torah — Don’t Be Satisfied

As long as we are reaching higher, we continue learning, loving, and living.

A Moment in Time: “Moments that Shape Us”

Confessions of a Bukharian Comedian ft. Natan Badalov

Marla and Libby are back with another episode of Schmuckboys. This week the duo start with their updates of the week. Libby shares about how her and Jack are celebrating one year of marriage. And the two talk about the exciting news of having a…

Charlie Kirk Brought Conservatism to the Cool People

He engaged with tens of thousands of college students in hundreds of campuses over more than a decade and stood tall with his coolness and his arguments. He wanted to make loving America cool again.

Print Issue: Countdown to Repentance | September 12, 2025

With the world and so many lives in turmoil this year, how best to prepare for the High Holy Days? One answer is in Pirkei Avot, “The Sayings of the Fathers.”

A Big Kitchen Anniversary, High Holidays and Sumptuous Dishes

Saffron Scents: Paella Valenciana

Paella is perfect for any festive occasion or as a one pot weeknight meal. It is easy to make ahead and to reheat for stress free entertaining!

Table for Five: Ki Tavo

Connecting To God

Ten Secrets to Academic Success | Make for Yourself a Teacher – Acquire a Friend

Fourth in a series

Countdown to Repentance: Thoughts Before Rosh Hashanah

As I study Pirkei Avot at this time of the year, the Days of Awe hover in the background. As my inner preparation for the Days of Awe coincides with my study of Pirkei Avot, unexpected connections emerge.

Cutting-Edge Faith on Rosh Hashanah

How can a sophisticated modern Jew integrate the pious promises of our tradition with the tragic and often painful reality of our world and our lives? Perhaps we can use these 10 days to reflect on these timeless and timely questions.

Hamas’ Big Lies: Blaming Israel for Their Own Crimes

Hamas is not just guilty of the crimes it accuses Israel of; it is defined by them.

Rosner’s Domain | A Generation Remembers; A New One Forgets

The political paradigms that dominate Israel today weren’t born on Oct. 7 – they were forged in September 2000.

Welcome Back, Jewish and Pro-Israel Students. Here’s What to Expect.

How will a combined student body of millions of undergraduate students marinated in an antisemitic miasma on social media receive its Jewish peers this fall? If the past is any indication, we should buckle up.

Babette Pepaj: BakeBot, AI Recipes and Cupcakes with Apple Buttercream

Taste Buds with Deb – Episode 124

More news and opinions than at a

Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.