Aronofsky’s Original Formula

By Naomi Pfefferman, Entertainment Editor

Debut filmmaker Darren Aronofsky manages to sound incredulous about the Jewish sci-fi flick that has made him a star. “You don’t think God, math and bad-ass Jews makes for a Hollywood movie?” he quips of “PI,” which won the director’s prize at Sundance and a $1 million distribution deal.

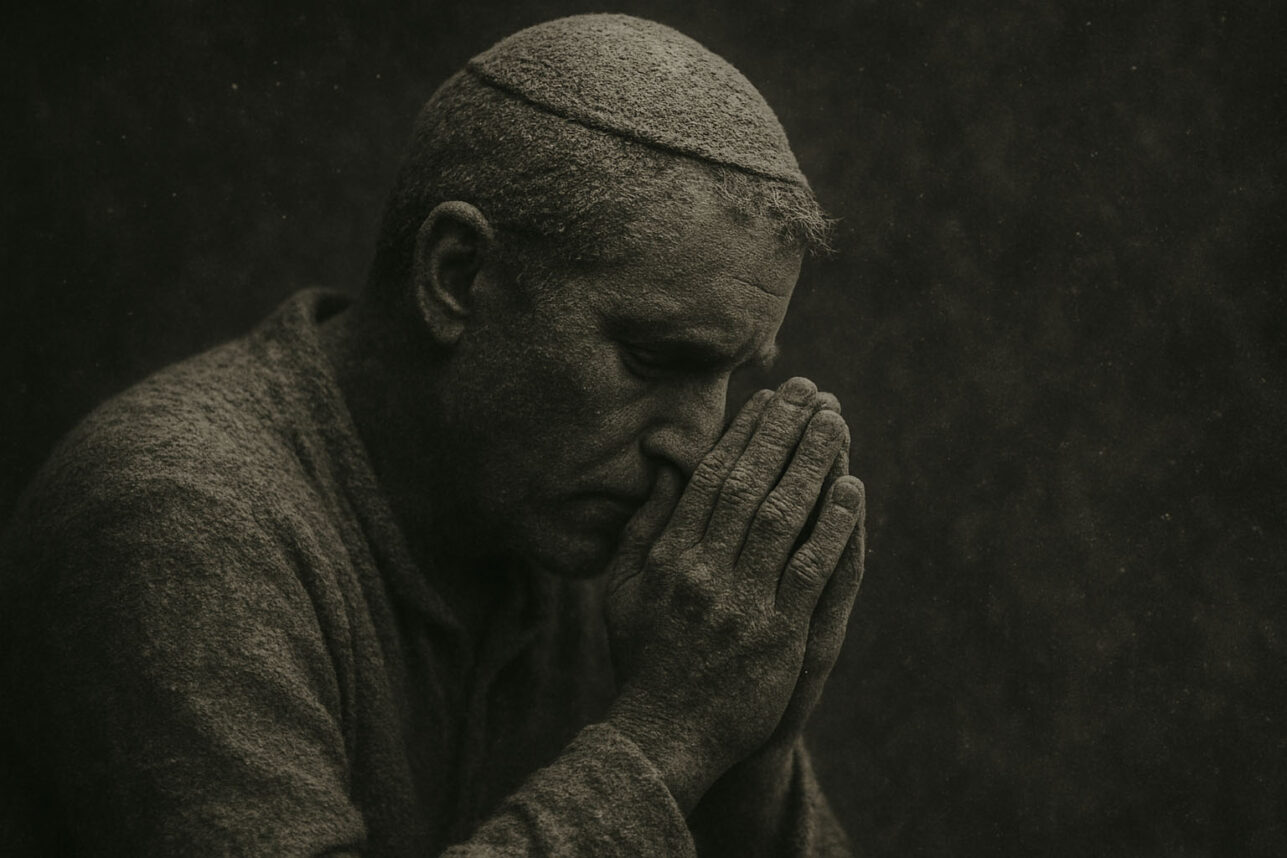

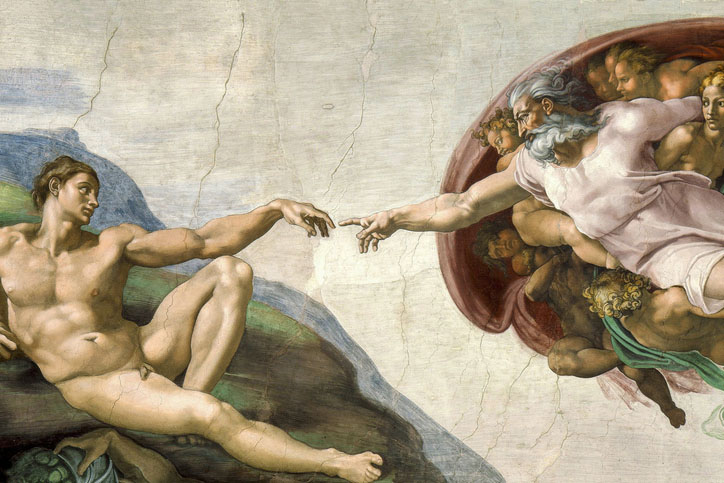

The disturbingly visceral thriller (you could call it “Eraserhead meets Frankenstein”) features neither aliens nor humongous reptiles. Rather, it centers on mad Max Cohen, a tortured, paranoid mathematics genius on the verge of a startling discovery. For a decade, he’s been trying to decode the hidden numerical system that governs the universe and, specifically, the stock market. On the brink of success, he is pursued by representatives of a sinister Wall Street conglomerate and a Chassidic sect bent on dissecting the numerological codes of the Torah. When Max’s supercomputer spits out a number that may signify the ancient Hebrew name of God, it’s a secret some are willing to kill for.

The Kafkaesque, hallucinatory “PI,” which has jarring, grainy black-and-white images and a fingernails-on-the-blackboard score, recently broke box-office records in New York. It’s not for everyone, however. While many of the notices have been glowing, some reviewers have deplored what they perceive as the film’s “freakazoid intensity,” “film-school-style trickery,” glib theology and “midnight movie” attitude. Yet even the less-than-ecstatic notices have praised Aronofsky’s talent and referred to “PI” as “smart” and “engrossing.”

During a recent telephone interview, Aronofsky, 29, wasn’t as concerned about the reviews as he was his depiction of, well, “bad-ass” Jews. “Any time you put the words ‘Jew’ and ‘conspiracy’ in the same sentence, you’re treading on dangerous ground,” says the director, a graduate of Harvard and the American Film Institute.

Nevertheless, he insists, New York audiences have been cheering on the Chassids, whose intentions are noble. The religious Jews want to usher in the Messianic age; plus, they counter what Aronofsky perceives as the ubiquitous film stereotype of Jews. “I’m tired of the victim image,” he says. “I wanted to smash it. I wanted my Jewish characters to have more of an edge.”

Aronofsky says that he grew up amid “tough Jews” in Brooklyn, where his father taught science at Yeshiva of Flatbush. He was “a typical, bratty Hebrew-school kid” who preferred science fiction to Judaica; who wrote book reports on Rod Serling; who pretended the gears of a pocket watch were his bionic guts.

His feelings about Judaism changed when he visited Israel after graduating high school, although the trip got off to a rocky start. Aronofsky arrived with dreams of picking avocados in idyllic fields; instead, he was put to work in a kibbutz plastics factory, where he felt like a character from “Modern Times.” He fled in the middle of the night two days later, and ended up shekel-less and homeless in Jerusalem. While hanging out at the Western Wall, he was approached by members of a Chassidic sect who offered him free room and board if he studied each morning at their yeshiva.

It was at the sect’s headquarters and later at Aish HaTorah’s “Discovery” program that Aronofsky first learned about kabbalah and the famous “Bible codes.” He was so fascinated that when he began Harvard several months later, he spent hours perusing esoteric books in the library and researching Jewish mysticism, parallels between Purim and the Holocaust, and, especially, gematria . “I was possessed,” says the filmmaker, who ultimately merged his obsession with the work of several “bizarre conspiracy theorists” to invent “PI.” He completed the film before the publication of Michael Drosnin’s best-selling book, “The Bible Code.”

Aronofsky says that he most resembled his tortured protagonist as he struggled to write “PI,” “hunched alone in a room, suffering.” He often wrote the script in the homes and offices of friends and relatives, hopping from location to location whenever he felt his muse wane. As research, he interviewed several visiting Israeli kabbalists; he also turned to Yisrael Lifschutz, founder of the Hassidic Actors Guild, whose motto is “pay us for pais .” Aronofsky and producer Eric Watson scraped together the $60,000 budget, in part, by soliciting $100 donations from friends, relatives and shul members.

Their efforts paid off, big time. The temple members are getting a 150-percent return on their investment. And Aronofsky is getting nearly $1 million to write and direct his next film, “Proteus,” about a U.S. submarine dodging Nazis and monsters during World War II. He also has been signed to develop and direct the feature adaptation of the comic book”Ronin” for New Line Cinema. If it gets produced, he stands to pocket $650,000.

“Proteus” also has a Jewish theme, but Aronofsky isn’t worried about being typecast as a Jewish director. “I want to make a movie about the Warsaw ghetto uprising, and I’m adapting Hubert Selby Jr.’s book, ‘Requiem for a Dream,’ in which several main characters are Jewish,” says the filmmaker, who still shares a Hell’s Kitchen, N.Y., flat with Watson. “One day, I’ll also make a movie about my Hebrew-school classmates, a bunch of smart, smart-alecky guys I’m still friends with today.” Aronofsky pauses, then laughs. “It will be like a Jewish ‘Stand By Me.'”

Above, Sean Gullette, left, and Ben Shenkman from a scene in “PI”

The Emperor Has No Clothes

At a recent screening of “PI,” 28 critics were in attendance. Seven departed before the film was over, while the woman on my left dozed fitfully through most of the film. This should serve as fair warning that “PI” faces some difficulties and has received, silently at least, a mixed reaction.

The reasons for the rejection are visible on the screen. Shot on a low budget of $60,000, there is considerable voice-over and little dramatic action, and the print is assaultive, with harsh contrasts of black and glaring white light, so that the film resembles one of the early German expressionist efforts of the late 1920s.

Depending on your outlook, the story is either a profound commentary on purity and obsession, or a jejune and pretentious clump of clichés, thinly disguised by the overlay of science fiction. I side with the latter view.

What makes “PI” interesting is that its director-writer received $1 million to make his next film, “Proteus.” It suggests to me that the instant an artist is labeled as the newest experimental figure in films, art, literature, etc., or the moment he or she is acclaimed at Sundance, he or she is quickly transposed onto the pages of Time, Vanity Fair, Vogue; morphed into a segment on “Charlie Rose;” and nestled somewhere on the Internet.

There is no time for the “experimental, cutting edge” nature of the work to evolve into a finished film or, as is more often the case, simply to disappear mercifully from view. Instead, to be identified as a “hot” prospect is to be granted fame of a sort for a while, and to be embraced by Hollywood and the mass media.

What is notable about “PI” is that its director was quickly given a $1 million film deal. Granted, that may be walking-around money, and its purpose simply a way for producers to cover all their bets. — Gene Lichtenstein, Editor in Chief