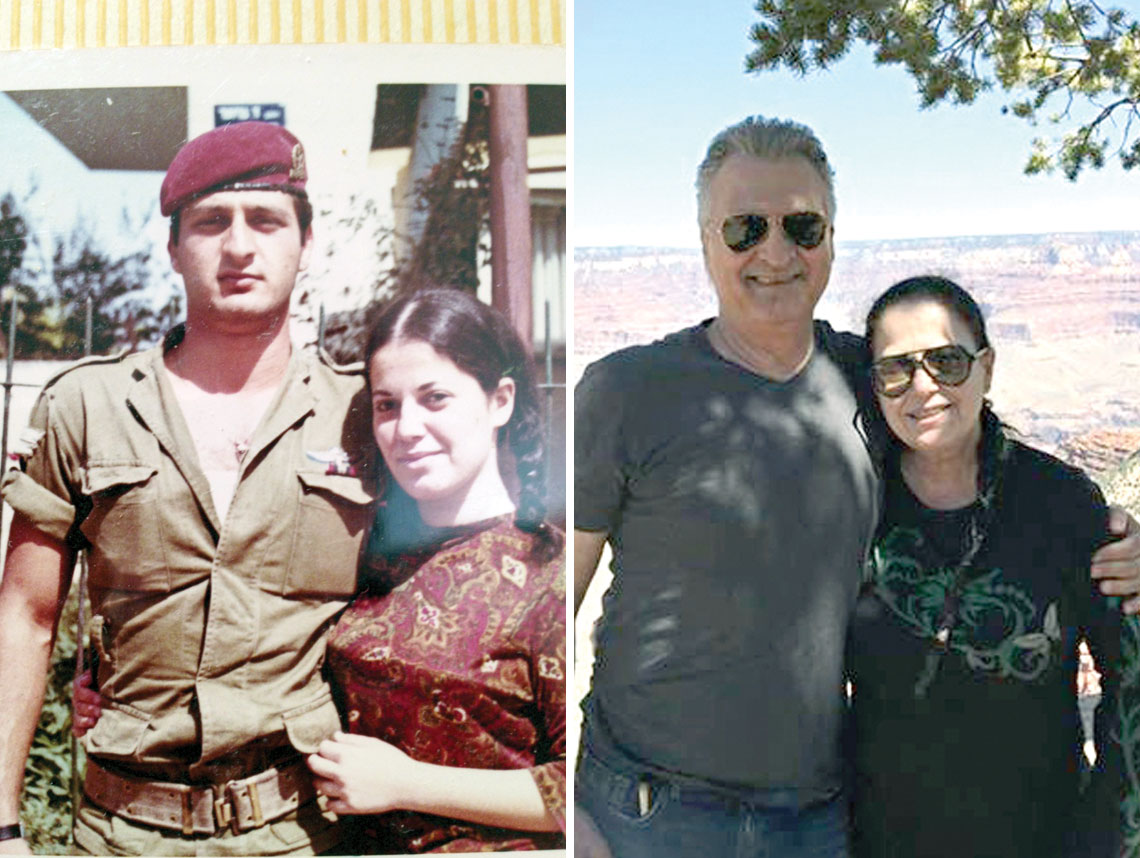

Left: David Bahat, wearing the red beret of the Israeli paratroopers, with his wife, Hannah, in 1968, shortly after his service in the Six-Day War. Right: David and Hannah at the Grand Canyon in April. Photos courtesy of David Bahat

Left: David Bahat, wearing the red beret of the Israeli paratroopers, with his wife, Hannah, in 1968, shortly after his service in the Six-Day War. Right: David and Hannah at the Grand Canyon in April. Photos courtesy of David Bahat David Bahat used to marvel at the paratroopers who would practice their jumps near where his family lived, in a refugee camp outside Tel Aviv.

His parents brought him there from Baghdad in 1951 and moved into a shack in Kiryat Ono. The contrast between dirt-poor immigrants like Bahat and the men heroically throwing themselves from planes was vast. He and his elementary school friends used to ditch class to watch them.

“We were fascinated to see the people jumping,” he said in an interview in his Encino home. “I was maybe 8 years old at that time. I said, ‘I want to be a paratrooper.’ ”

Less than 10 years later, Bahat lived up to that dream, donning the red beret worn by the elite soldiers. But he describes his own service fighting with Hativat HaTzanchanim, Israel’s legendary paratroopers brigade, in 1967 as nothing more than an ordinary man called on to do his duty.

“I don’t consider myself a hero,” he said. “I just happened to be a young paratrooper who was in the service at that time and ended up in the war.”

Bahat agreed to an interview only reluctantly, worried about portraying himself as something extraordinary rather than a person who just did what was expected of him in the service of his country. Eventually, though, he agreed to meet a reporter at his townhome, answering the door on his day off in gym shorts and an AC/DC T-shirt. “I’m a classic rock kind of guy,” he explained.

Bahat, 67, was a 17-year-old soldier when tensions began to escalate between Israel and its neighbors in May 1967. He and his unit were sent to the Negev Desert to await action, where they slept under the stars, battle ready.

“We were on alert for, like, three weeks, like sitting ducks just waiting for the war,” he said.

Bahat saw combat during the six days of hostilities, “but it’s something that I don’t like to talk about. It’s war,” he said.

Instead, he chose to recall other memories, like listening to the news that came in from the other theaters of battle — of victories in Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. As much as they could, other units kept Bahat and his companions up to date via radio with what was going on. Meanwhile, he said, an Egyptian station was broadcasting false news reports in broken Hebrew aimed at demoralizing the Israeli troops, relating how Arab armies had taken Tel Aviv.

Tuning into the broadcasts from his fellow soldiers scattered across the country, Bahat was particularly moved to hear about the unification of Jerusalem under Israeli rule. He used to spend his summers there as a kid, visiting relatives, and always was confused when he turned a street corner and suddenly came face to face with barbed wire and barricades.

“I couldn’t understand,” he said. “It’s like you go on Ventura Boulevard and all of a sudden there’s a border there. As a kid, I could not comprehend that. … So when I heard in Sinai in the war that Jerusalem was liberated, the first thing that came to mind was, ‘Now I can actually cross that street.’ ”

Another cherished memory comes from the second day of the war, when Mike Burstyn, the Israeli-American actor and singer, came to entertain Bahat’s unit at Rafiah.

The soldiers arranged their jeeps and turned on their headlights to create a makeshift stage, and Burstyn pulled out a piece of paper on which singer-songwriter Naomi Shemer had written the lyrics to her new song, “Yerushalayim Shel Zahav” (Jerusalem of Gold), which would later become an anthem for a reunified Jerusalem. For years afterward, Bahat would tell his wife that the first time he heard the song was from Burstyn in the midst of war and chaos in the Sinai Desert.

About five or six years ago, Bahat ran into Burstyn at an event in Los Angeles and reminded the performer about the show in the Sinai.

“We both were crying,” Bahat said, choking up at the recollection. “He didn’t believe he could see a guy after 40 years here who remembered that he came to Rafiah the second day [of the war].”

After finishing his military service, Bahat returned to civilian life and married his elementary school sweetheart. In 1976, with two young daughters in tow, they moved to Los Angeles and ended up in the San Fernando Valley, where Bahat works in the jewelry business. With his wife, Hannah, an administrator and teacher at Wise School, he has eight grandchildren.

From time to time, he talks about his wartime experiences with his grandchildren, to make sure they understand the State of Israel and its origins. But sometimes, they just want to hear about his exploits.

“ ‘Saba, how can you jump from a plane? Were you scared?’ ” he said, recalling their inquires. “All kinds of questions like that. They take pride.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.