A key takeaway from John Lewis Gaddis’ book “On Grand Strategy” — recommended reading that was translated to Hebrew not long ago — resonates profoundly: a nation fails to achieve its objectives when it does not align its goals with its capabilities. From this principle, all else follows: The Chief of the IDF warns the politicians that there aren’t enough soldiers to fulfill their aspirations. The ensuing choice is binary: either reorganize the objective board, set priorities, and decide what’s essential now, what can be postponed for later, and what can be ditched — or find a realistic way to bolster manpower so the goals can be pursued.

Here’s a mundane yet revealing story. The details have been altered slightly to obscure identities. Recently, commanders of an Israeli reserve unit slated for mobilization were summoned for a preparatory meeting — a briefing, a tour of the area, and familiarization with their tasks. About 90 reservists were called in. Only 35 showed up. And these were commanders, not the rank and file. Disappointing? Certainly. Predictable? Arguably, yes. Challenging? Undoubtedly.

The younger generation of Israelis (and quite a few of the older ones) have demonstrated over the past year-and-a-half that when the mission is clear and the urgency is palpable, they show up with determination, courage, and willingness to sacrifice. They now prove with their growing absence that they neither perceive a clear mission nor a pressing urgency. What they perceive is evasion, a dodging of uncomfortable decisions.

An example of an uncomfortable decision that could be made: conceding some war objectives due to manpower shortages. Politicians could decide that matching capabilities to objectives necessitates such moves. This would require them to look at the list of desired tasks and decide which objectives are absolutely crucial and which are less so. Of course, this involves taking certain risks. Giving up on any way objective involves risk. It would compel the leaders to ask fundamental questions about Israel’s possibilities in a complex arena filled with numerous actors, constraints, and limitations. It would require them to face the public — possibly their own supporters —and explain a decision that will invariably sound negative. “We decided to withdraw forces from the Syrian Golan” — this sounds bad, defeatist. “We decided to thin our number of forces in Judea and Samaria” — this sounds risky. “We’ve decided not to continue the maneuver in Gaza, although Hamas still controls the area” – this sounds miles away from “total victory.”

So one uncomfortable option given the reality that has emerged is to change the objectives to match the capabilities. Another uncomfortable option is to take the opposite route: to strengthen capabilities in order to meet the original and emerging objectives.

What does this option entail? It requires a significant increase in military manpower, and this increase must be based on a realistic plan of recruitment. There is only one place where enough young people remain to fill the IDF’s needs: the Haredi sector. But etting these youngsters is highly uncomfortable. It would destabilize the coalition, complicate the continuation of government tenure, and rupture the political alliance of groups that hold significant power. Not to mention the actual difficulty of recruitment. Uncomfortable.

In recent weeks, while filming episodes of my video series on the “Haredi Challenge,” I met with several professionals who have dealt with manpower management in Israel’s security apparatus. Not one — literally, not a single one — suggested an alternative to significantly increasing the combat force other than drafting young Haredim. Yes, they said, you can further explore the existing pool for manpower, find a few lost servicemen who haven’t yet been called up, bring back veterans. All this, as one of them told me, is “marginally beneficial.” Another one said: “The lemon is squeezed.” There are only two large groups of men who have not yet been drafted: Haredim and Arabs. Hence, for those who want a larger army capable of achieving all objectives, there is only one option, and it is not an easy option to implement.

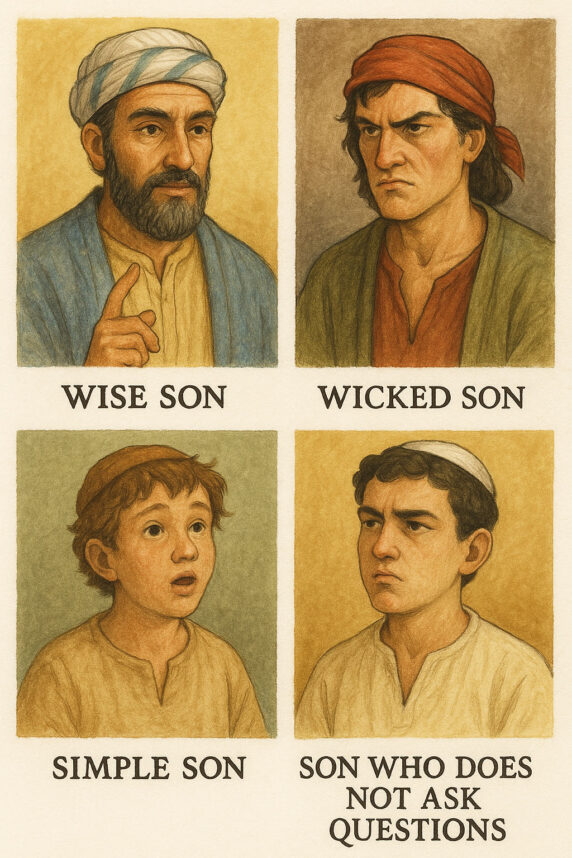

Two options. “How long will you keep hopping between two opinions”, prophet Elijah (the classic Passover source) implored the people when they failed to choose between to clear options. “If the ETERNAL is God, then follow [the ETERNAL]; and if Baal, follow [Baal]!”. Instead of choosing, they procrastinated, avoided the truth, hoped for some miracle that would save them from having to make a choice, shifted responsibility onto others. The prophet implores the people to choose the true God. They, like Israeli politicians today, “answered him not a word.”

Something I wrote in Hebrew

The IDF leadership decided to suspend from the reserves Air Force pilots who signed a letter protesting the current war aims. Here’s what I wrote:

Let’s be blunt: suspension from reserve duty is not a punishment for the signatories – it’s a punishment for the state. Whoever decided to suspend the signatories of the letters made a mistake that he will be forced to retreat from, as every suspension will lead to another letter, and every punishment will add more signatories, and the IDF is in a manpower shortage, not in a surplus. What will it do if a majority of a brigade signs a letter — not draft them? What will it do if it receives a petition from 10,000 reservists — forgo their service? … Those who think the right response to these letters is suspension from military service are wrong.

A week’s numbers

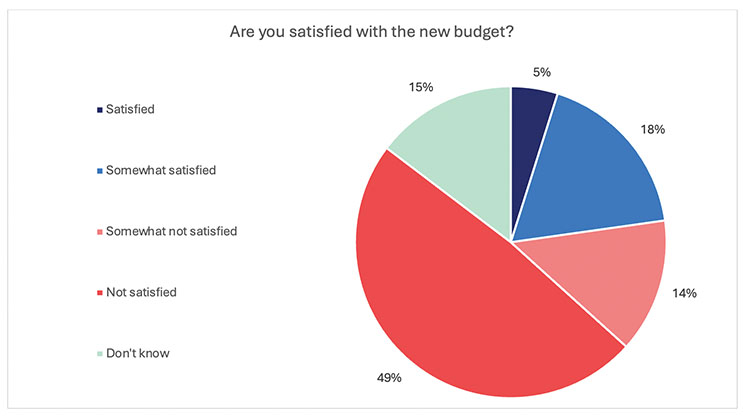

Economic issues are on everyone’s minds. There are tariffs, there’s also the new Israeli budget … (JPPI numbers)

A reader’s response

Elana Rosenberg: “Whenever I see Netanyahu cozying up to Trump I feel embarrassment.” My response: Sometimes a leader’s got to do what a leader’s got to do.

Shmuel Rosner is senior political editor. For more analysis of Israeli and international politics, visit Rosner’s Domain at jewishjournal.com/rosnersdomain.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.