Every time Tom Rose, chief executive and publisher of the Jerusalem Post, leaves his office at the newspaper, he passes by a bright yellow sign posted on his wall that screams “Tom Rose Go Home.” The sign is proof that he has no illusions about what his employees think of him, Rose jokes.

Many journalists at the newspaper believe that what they call the ruthless managerial tactics Rose has deployed since joining the newspaper in 1998 could spell disaster for an institution that has been Israel’s venerable voice to the outside world for decades.

Yet Rose remains sanguine when discussing plans to wrap up a labor dispute and push through sweeping job cuts. At the same time, he is trying to lead the paper past a turbulent time during which two senior editors have recently resigned.

“There really has not been a dramatic shakeup here in a long time,” Rose said, talking about plans to streamline the financially troubled newspaper. “The issue is really grow or die — and we choose the former.”

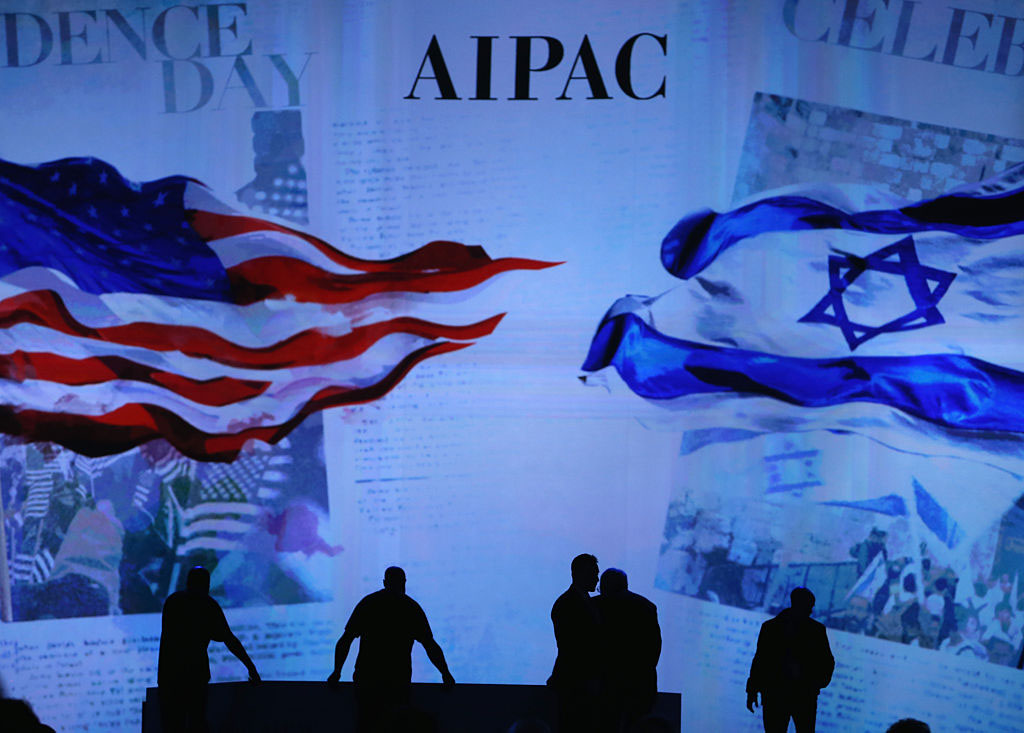

The recent unrest is the latest tumultuous chapter at the Post since it was taken over by Hollinger International, the Canadian newspaper conglomerate, in 1989.

Following the takeover, as the newspaper’s editorial line shifted from left toward center-right, more than two dozen journalists resigned. Many left to create the Jerusalem Report, today a bi-monthly magazine that also has been bought out by Hollinger to bolster an English-language media powerhouse in Israel. Yet the real trigger for the Post’s tricky situation today is competition.

For decades since its founding in 1932, the Jerusalem Post, known in pre-state days as the Palestine Post, was a monopoly in the small market for English speakers in Israel, today totaling about 150,000. But in 1997, Ha’aretz, a leading Hebrew daily newspaper, launched an English-language version together with the International Herald Tribune.

Although Rose says circulation has increased slightly since then, now that English-speaking Israelis, tourists and Internet readers have a choice, the Post has been challenged to improve. Both newspapers have strengths and weaknesses. Many readers consider Ha’aretz to be a premier source of scoops and higher quality analysis. But as a translated newspaper it is often not reader-friendly and is riddled with errors. It also has a left editorial line.

The Jerusalem Post is considered by many to be Israel’s English-language journal of record, though not always at the cutting edge of the political and business news fronts. According to Rose, its editorial line is strategically positioned at the center-right to capture the large number of right-wing English speakers in Israel without alienating readers of other political persuasions.

However, the recent resignations of centrists Hirsh Goodman, editorial vice chairman after nearly two years, and David Makovsky, executive editor after just five months, have led some observers to wonder whether the Post is poised to shift further rightward.

Goodman, who had initially left the Post when Hollinger took over to become editor in chief of the Jerusalem Report, says he stepped down for personal reasons. But Makovsky, who declined to comment for the record, is said to have resigned over an editorial dispute. Makovsky, a veteran diplomatic journalist, has reported in the past for the Jerusalem Post and Ha’aretz.

During his tenure, Makovsky had been asked to publish a regular opinion column by David Bar-Illan, a former editor of the Jerusalem Post who served as media adviser to former Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, on the front page. In the international newspaper industry, opinion columns are rarely positioned so prominently.

More recently, say Makovsky’s supporters, he was asked to write an editorial opposing the peace process with Syria. He also felt that the sweeping job cuts Rose planned to implement would cripple the newspaper and irrevocably damage its quality.

Rose rejected reports of an editorial dispute as “totally untrue” and added: “The editorial line has not changed and will not change.”

Jeff Barak, Makovsky’s predecessor, who is considered left of center, is poised to fill one of the vacant senior editorial positions later this year, Rose said.

Meanwhile, Rose is faced with labor problems that are no less daunting than the editorial issues. At the end of 1999, Post journalists who were on a collective union contract launched a series of demonstrations against Rose’s plans to change their contracts, which expired last month. They said the changes, which would make it easier to dismiss union employees, would leave them vulnerable to management and compromise their editorial standards.

“For a journalist, living in fear of losing your job for any reason is extremely problematic because one of the reasons for being dismissed can be that you’ve offended a client or a friend or a crony of the publisher,” said Esther Hecht, a union activist who works at the Post.

Hecht also warned that plans to cut the workforce dramatically would be catastrophic. “This paper has a very long history as the paper of record in English and Israel’s window to the world,” she said. “If the staff is cut to the point that there are not enough people to cover major beats, and the coverage and editing is done by people who don’t know the country because they just got off the boat, the paper cannot do its job properly.”

As the two sides work out a new contract, last week, Rose told the Post’s editorial staff that the newspaper was about to embark upon the equivalent of “basketball tryouts.” Post insiders say up to 35 percent of the newspaper’s 55 editorial employees may find themselves off the team, and union members are believed to be blacklisted.

Rose defends the job cuts, saying since the newspaper spends an unsustainably high amount of money on bloated contracts to union journalists.

“The whole issue is how to best position this paper in business for the future,” Rose said, promising that the Jerusalem Post will become a better-written newspaper that is more focused on issues of concern to English- speaking readers.

Post insiders say the plan may also include new agreements to buy outside content such as the recent launch of pages from The Wall Street Journal, and possibly, an agreement with an overseas Jewish newspaper such as the Forward.

But while some nonunion journalists think the cuts could position the newspaper for a brighter future, many remain completely confused by the strategy and say the plans remain shrouded in a thick fog.

Rose’s success or failure in clearing up that fog and leading the Post into the new millennium could impact not only the newspaper’s employees and reputation, but thousands of English-reading news junkies from Israel and abroad alike.