Have you ever been lost on Ventura Boulevard, a street that’s long on history? One night, I found myself west of the 405 Freeway, searching for the street on which to turn left to pick up my teenage son and realized I’d totally lost my bearings.

Separated from the San Fernando Valley by a range of mountains and life choices, I don’t come here often. A couple of Jewish weddings at the Sportsmen’s Lodge, visits to Valley Beth Shalom for our son’s Hebrew High School graduation, a family wedding at the L.A. Equestrian Center, and beyond that, for this Mid-City dweller, it’s the great ek velt (boondocks).

Trying to reset my compass as the storefronts rushed by, I searched for landmarks: a kosher restaurant, a synagogue, a large clock with Hebrew numbers. I remembered that I was supposed to turn left at a deli.

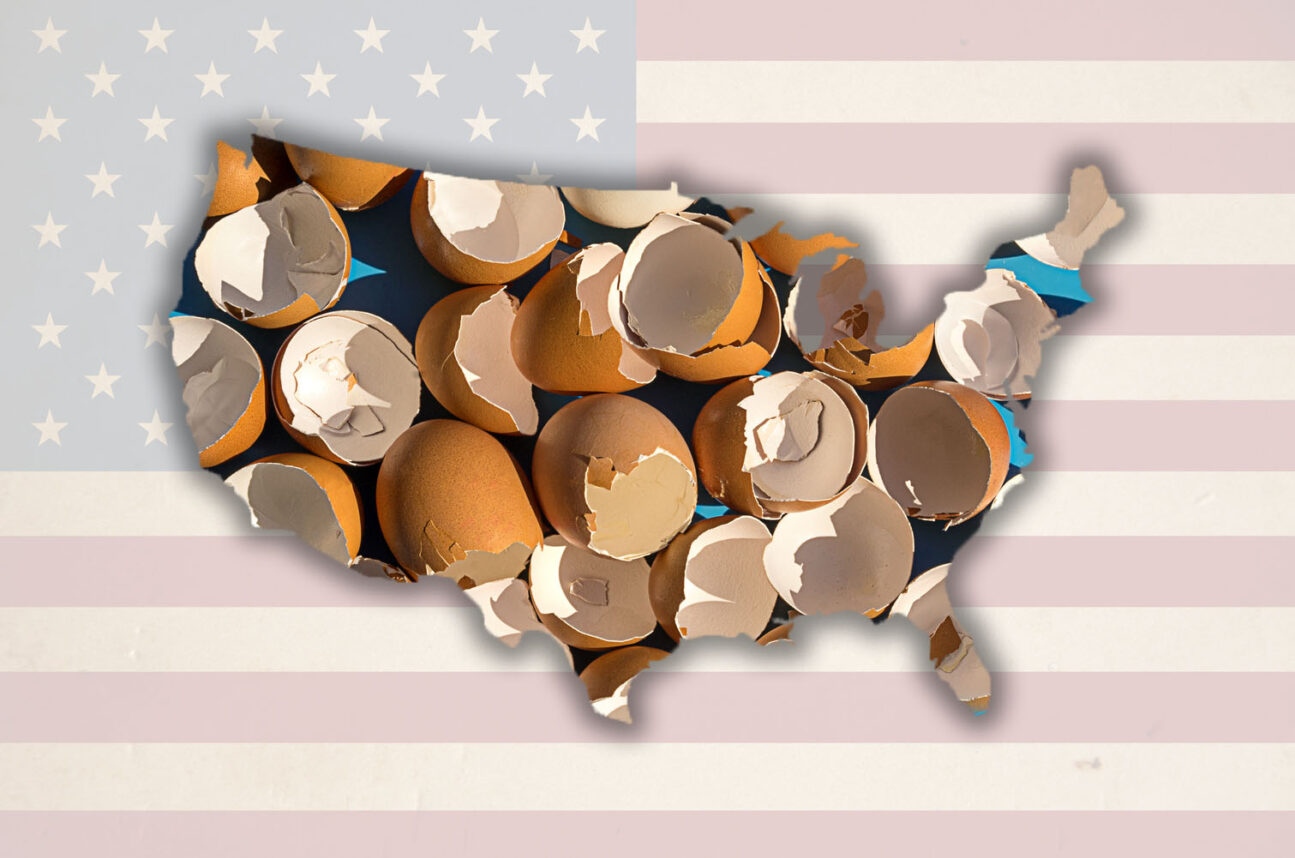

Demographically speaking, I knew where I was. Years earlier, I had edited a Los Angeles Jewish population survey. On a graph, a dense swarm of blue dots marked the area of Encino through which I was driving. Each dot represented a Jewish household, and each household represented a story of Jewish migration.

Some had moved there from Boyle Heights and the Adams District in the postwar boom years of the early 1950s. Others, since the 1980s, had moved from the city’s metro region looking for what they described in the survey as a “better area.”

But long before that, in the closing years of the 19th century and early decades of the 20th century — a time not counted in any survey — Jews also migrated to the San Fernando Valley, not so much because it was better, but because it was bigger and open, and they came to build dreams.

A few blocks later I found Jerry’s Deli and made my turn. But instead of heading up the street to get my son, I was drawn by the light of the deli case in the window and turned into the parking lot.

The case was jammed with stuffed cabbage, kugel and pickled tomatoes. But then I saw the pumpernickel. “An East Coast baker must have migrated to the Valley,” I remember thinking.

As I was discovering, the Valley was built on stories of Jewish migration, with even the wheat grown to make bread figuring prominently in its history.

Isaac Lankershim —yes, the boulevard is named after him — is introduced by the online Jewish Museum of the American West as both “Creator of the San Fernando Valley Breadbasket and Enigma.”

In the 1850s, Lankershim, who moved to the United States from Bavaria, made a name for himself in San Francisco, where he was known as the “Wheat King.”

In the late 1860s, Lankershim moved to Los Angeles, where, according to David Epstein, the co-publisher of Western State Jewish History (which created the online museum), Lankershim became associated with Harris Newmark and other Jewish businessmen. “The Jewish community thought of him as an idiosyncratic Jew,” said Epstein, who pointed out that though Lankershim had converted to the Baptist faith before moving to Los Angeles, “He thought Jewish,” Epstein said.

According to the museum, “In 1869, Lankershim and investors from San Francisco purchased 60,000 acres in the San Fernando Valley for $115,000, forming the San Fernando Valley Farm Homestead Association.”

The ranch consisted of what we know today as Woodland Hills, Tarzana, Encino, Sherman Oaks, Van Nuys and North Hollywood. It stretched from Roscoe Boulevard down to the crest of the Santa Monica Mountains, and from the Calabasas Hills to the western city limits of Burbank.

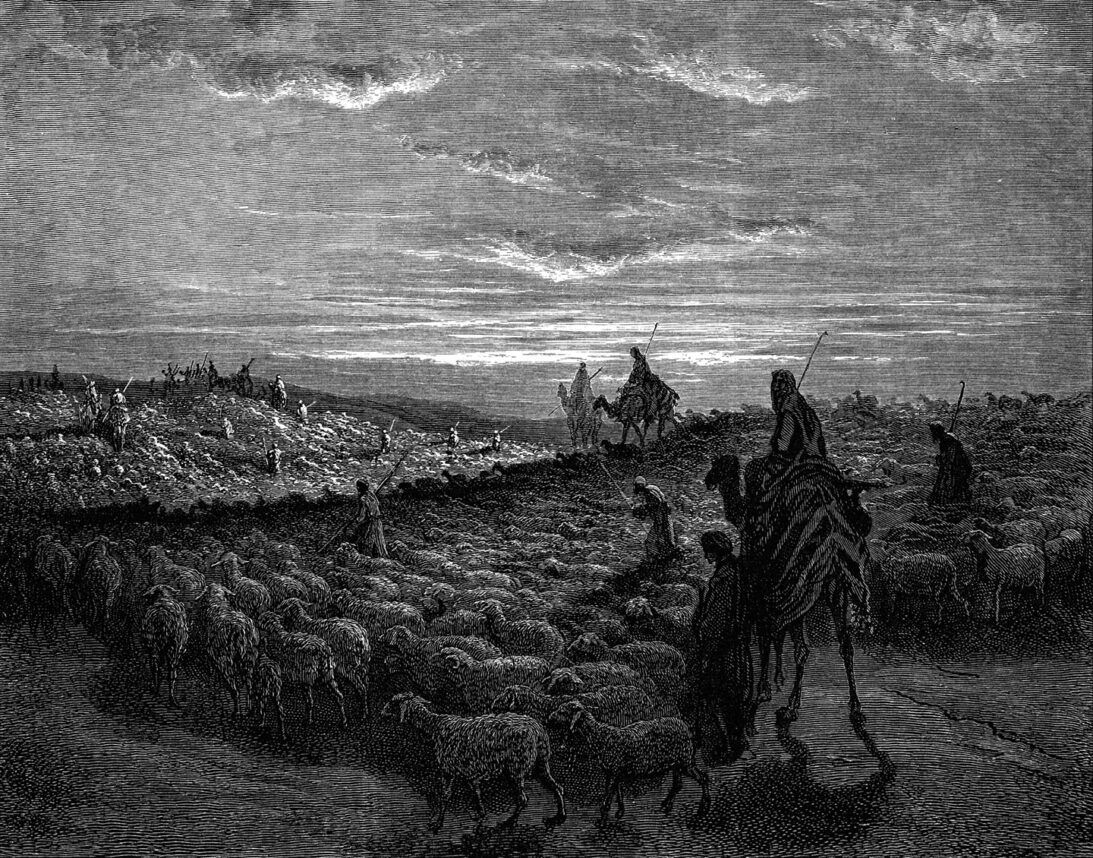

At first, Lankershim used the land to raise sheep, but after a drop in prices, he turned to farming wheat. Following a few seasons of drought, he harvested a crop so large that he had to build a wagon road to carry it to the pier in Santa Monica. The current 405 follows some of that same path.

In the following decades, Jewish dreamers and schemers began to subdivide Lankershim’s map.

In 1923, Victor Girard Kleinberger, a former imitation-Persian-carpet salesman, founded the town of Girard, which in the 1940s would change its name to Woodland Hills.

The Los Angeles Times has called him “a land huckster with big dreams.” But, Betty Bowler, the historian for the Woodland Hills Country Club, which she said was founded by Girard in 1925, prefers to think of him “as a dreamer.”

“We have Jewish weddings and bar and bat mitzvahs here,” she added.

In 1899, Girard — who had dropped his last name — moved to Los Angeles. According to Kevin Roderick’s book “The San Fernando Valley: America’s Suburb,” the young real-estate tycoon started Girard on 2,000 hilly acres. His plan was to subdivide and sell tiny lots — 25 feet wide, just large enough to build a cabin.

To attract prospects to the part of the West Valley that had no street cars and was accessible only via a Sepulveda Pass much steeper and serpentine than it is today, Girard booked “sucker buses,” to bring them to his development.

Wanting to create the illusion of an up-and-coming city, according to the Times, Girard erected false storefronts. On the corner of what is now Topanga Canyon and Ventura boulevards, Girard built a “Turkish city” — an assortment of minarets and gates.

In 1929, the stock market crash, as well as reports that he had double-sold some of the parcels, spurred Girard to leave, along with some of his town’s residents.

As to his legacy, in Woodland Hills today, many of the more than 100,000 eucalyptus, pepper and other trees Girard planted on the hillsides can still be seen along Canoga Avenue, south of Ventura.

Some of Girard’s original cabins still exist, though many have been modified. “I feel like I’m on vacation every day living here,” said Heide Bowen, who has rented one of the original cabins for the last six years. “It’s tiny, cozy and has a fireplace,” she added.

In the 1930s, another Jew, movie star Francis Lederer, would also leave his mark in the San Fernando Valley by building a mission-style home on a 300-acre ranch in what is today West Hills.

After a successful acting career in Europe on both stage and screen, Lederer came to America in 1932 to be on Broadway. Seeing what was happening in Europe, he decided to stay.

“The grim events in Germany are a lesson to the whole Jewish race,” Lederer said in 1934, as reported by JTA.

The handsome matinee idol, memorialized by a star on Hollywood Boulevard, played the lead in such films as “The Gay Deception” and “One Rainy Afternoon,” eventually appearing as the lead in “The Return of Dracula” in 1958. Also that year, he played Otto Frank in a theatrical production of “The Diary of Anne Frank” on a U.S. tour.

Lederer’s Spanish Revival home, built with the help of John R. Litke of natural stone and meant to look old, sits on a hilltop on Sherman Way. In 1978, the house was declared a Los Angeles landmark. A nearby mission-style stable, also built by Lederer, was also declared a landmark and today is an event site, known as the Hidden Chateau and Gardens.

Lederer’s house is now on the market, and, according to real estate agent Sarah Cartell, the Lederers used to “shoot up fireworks to let the neighbors know when cocktail hour had started,” she said.

Jill Milligan, the proprietor of the Gardens, who knew Marion Lederer, Francis’ third and last wife, said, “Marion would have liked to have the property seen as a tribute to Francis, who has had such a legacy in the West Valley.

“For many years, Francis was an honorary mayor of Canoga Park,” she added about the movie star who died in 2000 at the age of 100.

Dan Brin, president of the West Hills Neighborhood Council and former editor of the now-late Jewish newspaper The Heritage, added of the home: “I’m very much in favor of somebody stepping forward and making it possible for the entire community to enjoy this resource.”

Back at the deli, where this journey through San Fernando Valley Jewish history began, I bought a loaf of bread and drove up the hill to retrieve my son. Taking the same route as Lankershim’s wheat to get home, we headed through the Sepulveda Pass.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.