One verse, five voices. Edited by Nina Litvak and Salvador Litvak, the Accidental Talmudist

And Jacob gave Esau bread and lentil stew, and he ate and drank, and he rose and went on his way; thus Esau despised his birthright.

– Gen. 25:34

Gila Muskin Block

Executive Director, Yesh Tikva

We all know the story: Esau is hungry and wants to buy a meal of bread and lentil stew. Jacob agrees, but only on one condition, Esau must first sell him his birthright. The story concludes with our parsha: “And Jacob gave Esau bread and lentil stew, and he ate and drank, and he rose and went on his way; thus Esau despised his birthright” (Gen. 25:34).

At first glance, the detail about Esau eating and drinking seems almost superfluous. Why does the Torah tell us this? The Bekhor Shor offers a compelling explanation: the parsha clarifies that even after Esau ate, drank, and regained his strength, he still despised his birthright. His choice was not the product of momentary hunger or weakness. It was not a lapse in judgment that faded once he was sated.

Indeed, Esau’s willingness to trade something eternal for something fleeting remains intact even after he is nourished. He is calm, deliberate, and at peace with the transaction. The Torah emphasizes this to show that Esau’s birthright, his spiritual inheritance, holds no weight in his eyes.

Despite Esau’s blindness to its worth, Jacob, our forefather, recognizes the profound value of the birthright and eagerly acquires it. He sees beyond the immediate, understanding the spiritual inheritance it represents. The lesson I take from this story is to pause and consider the value of the gifts, responsibilities, and opportunities entrusted to us, and to cherish them with the clarity and purpose of Jacob.

Baruch C. Cohen

Los Angeles Civil Trial Attorney

THE MEAL THAT EXPOSED A SOUL

On the surface, the scene is simple: a hungry man, a bowl of stew, a quick meal. But the Torah is never that simple. It paints the moment with devastating precision. Esau comes in from the field exhausted, driven by appetite, consumed by the urgency of now. Jacob offers him bread and lentils. Esau eats, drinks, rises and walks away. Then the Torah reveals what actually happened beneath the surface: “Thus Esau despised his birthright.”

This was not a foolish bargain. It was a spiritual diagnosis. Esau’s flaw wasn’t that he sold something precious, it was that he felt no reverence for it in the first place. The birthright represented destiny, responsibility, covenant, the weight and wonder of the future. But Esau lived only in the present moment. If it didn’t satisfy immediately, it held no value. Jacob saw eternity behind the invisible. Esau saw only his hunger.

And so this becomes not a story about two brothers, but a story about us. Every day, the Jacob within us reaches upward, toward meaning, purpose, slow greatness. And every day, the Esau within us lunges for comfort, distraction, and the warm bowl of “right now.”

The danger isn’t the stew. The danger is letting the stew define what matters. Esau didn’t merely relinquish the birthright, he walked away full but spiritually empty, unaware of the greatness he abandoned. The Torah leaves us with a single, piercing question: What sacred possibilities are we trading for momentary relief?

Rabbi Ari Averbach

Host, “Moral Courage” podcast, Temple Etz Chaim

Judaism is built on the idea that we can disagree with each other and still remain civil. In so many other parts of our lives, if we don’t see eye-to-eye, then the conversation is over. In Midrash and commentaries over the course of millennia, sages posit what they believe the Torah is saying in its holy concision, and we hold multiple truths at once.

A favorite example is on this one line of Torah. Ibn Ezra, a Medieval Spaniard who wrote thoughts on nearly every verse of the Bible, read this line and said, “Clearly, Isaac and Rebecca had no wealth, which is why there wasn’t a fight over the birthright.” It would be like arguing over half of dad’s failed business. He then goes on to give several examples from the Torah that seem to support the claim that Isaac and Rebecca were destitute. A century later, Ramban, more of a mystic, wrote, “Ibn Ezra is totally confused. How can he be so blind? It is laughable!” (Ooh … drama between rabbis!) He notes that there are five verbs in a row in this sentence. Esau ate, drank, rose, went and despised. “Fools have no desire for anything but immediate pleasures, taking no thought for tomorrow.”

He contends that Esau is denied the birthright and the blessing because he is only interested in instant gratification. The one who carries the torch of sanctity must always be thinking of how it affects the next generation. And we still do.

Dr. Sheila Tuller Keiter

Judaic Studies Faculty, Shalhevet High School

Who would make the better action figure, Jacob or Esau? Jacob is great, but Esau comes with a fur robe and hunting bow accessories. Esau is the man of action, especially in this verse: Esau eats, drinks, rises, and goes, four verbs in rapid succession, and then he disparages. How do those four actions connect to rejecting his birthright?

Some argue Esau lives purely in the physical realm, acting solely to satisfy his physical desires. He despises the birthright because he rejects the spiritual legacy of Abraham and Isaac. This argument certainly succeeds if what Esau rejected was the brit, the covenant. But here Esau rejects the birthright, i.e. his inheritance rights. Nothing could be more material than inheritance. Rather, Esau, the man of action, aspires to live by the fruit of his own labors, to be a self-made man. He hunts for his sustenance. He depends on no one. Yet, for once, he is forced to rely on his brother’s kindness and humble food. What shame he must have felt accepting Jacob’s charity! No wonder he despises his birthright. He never wants to inherit, to take handouts, to be reliant on family kindness again.

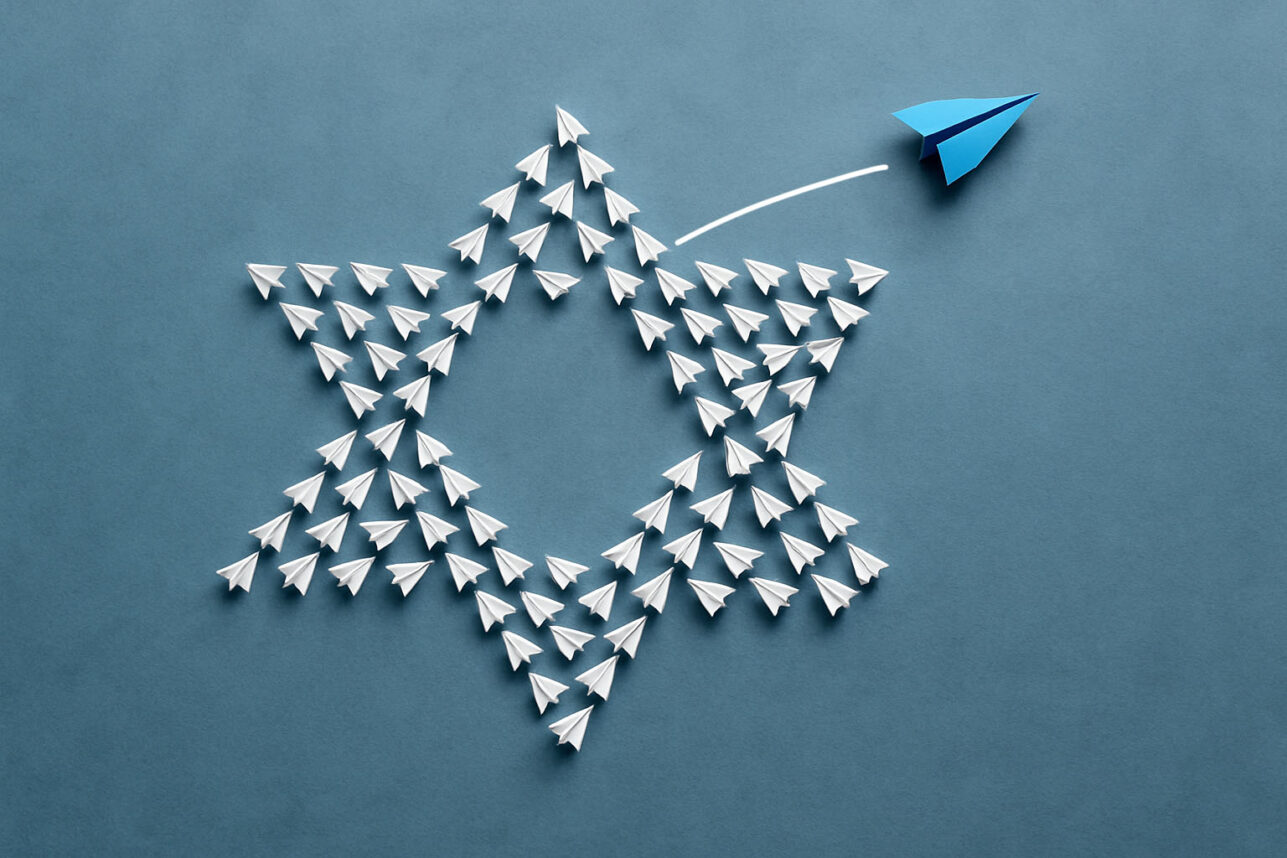

Esau’s defiantly individualistic spirit is admirable, yet our tradition places a premium on collective responsibility. We rely on family and communal support, which creates a reciprocal responsibility to sustain the institutions that support us. The Jacob action figure doesn’t come with cool accessories. Rather, he makes himself an accessory to the rest of Am Yisrael.

Rabbi Nicholas Losorelli

Jeffrey & Allyn Levine Assistant Dean, AJU Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies

Our patriarch Jacob, who famously wrestled with a divine being earning the name Israel, took advantage of his brother Esau, who had just returned from hunting. Jacob saw Esau famished at death’s door, and though you would expect him to do anything to save his brother’s life, he didn’t. Instead, Jacob put his brother in an impossible predicament: “I see you’re starving to death, and I’ll give you food, but only if you first give me your birthright.” Is that a choice? No! In his fragile state, Esau is compelled to say, “I’ll give you whatever you want.” And, despite this profoundly fraught moment, Jacob is still our heroic patriarch. Why?

Well, Jacob wasn’t always a hero. He hadn’t yet faced his choices and wrestled with the divine and human, he was still a scared child subject to the dynamics of his parents, and as a result he made decisions not of his own making, but certainly of his own doing, and while he is not responsible for the making, he is responsible for the doing.

What does this tell us? It tells us that if we have agency — the ability to do something — then we must take that agency seriously. When faced with issues not of our own making, we stand with the agency to make the same choices that got us there, or to make different choices. And to make a different choice in moments like these, can be a truly heroic act worth remembering.