Nobody likes to contemplate — let alone talk about — one’s own death or that of a loved one. However, now that medicine has advanced to the point that it can keep people alive, with or without consciousness, long past the stage that they themselves would have wanted to live in that diminished way, it is imperative that we all have these conversations with our loved ones. They need to know what we would want to be done to keep us alive and when we want just to be kept comfortable and let nature take its course.

As the philosopher Immanuel Kant pointed out, “can” does not automatically mean “ought.” The fact that we now can keep people alive through all sorts of medical interventions does not mean that, in every case, we should.

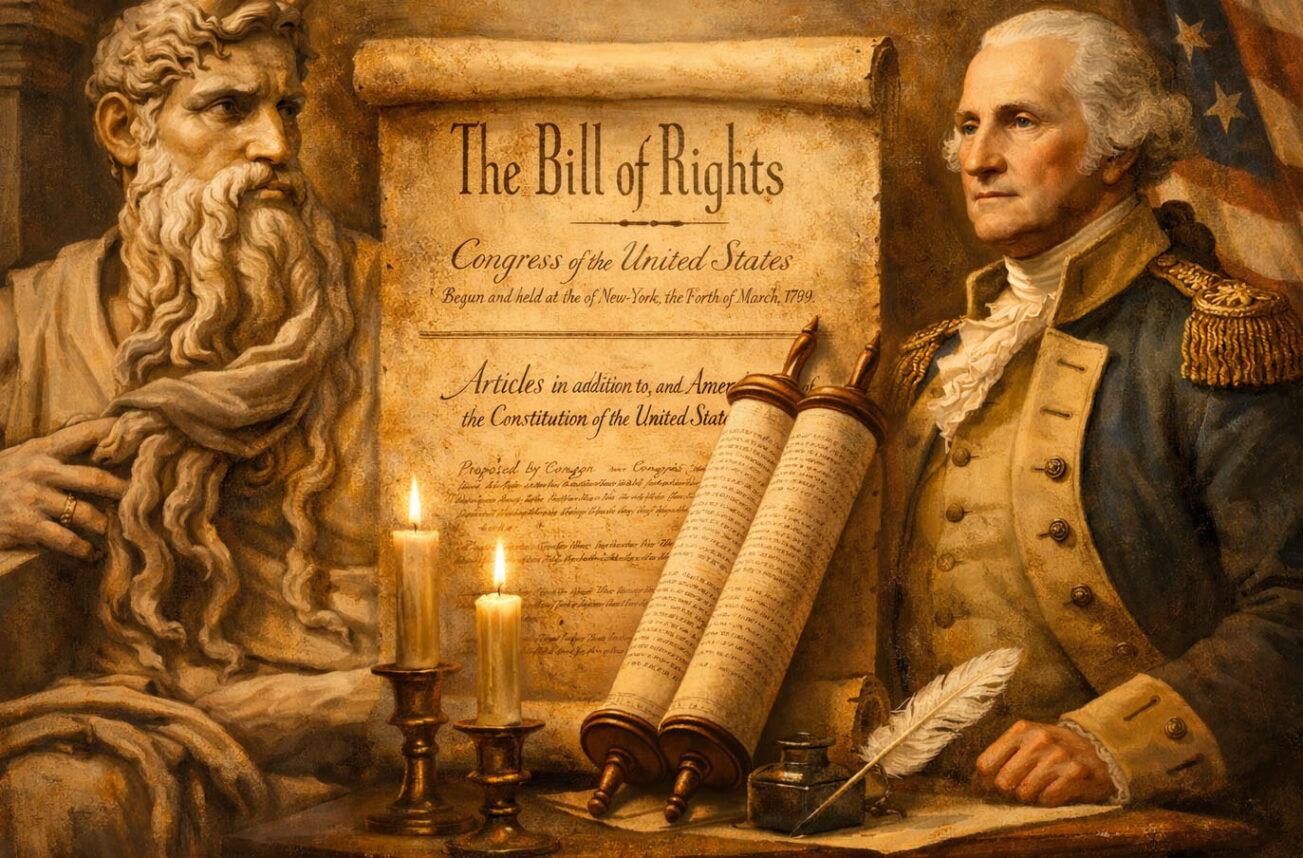

To make it possible for people to express their wishes about their mode of dying, all 50 states, beginning with California in the 1970s, have given legal authority to advance directives. An advance directive consists of two parts: a durable power of attorney for health care and a living will.

In the durable power of attorney for health care, a person designates a surrogate decision-maker when he is no longer capable of making his own health care decisions, and alternative people if the first surrogate is not willing or able to function in that capacity when the time comes. In California, the document must be signed by two witnesses or notarized.

In a living will, the document presents some decisions that people who are dying commonly need to make with regard to their health care and asks the writer to make choices among the various options. For reasons described below, it is best to give the person designated as the surrogate decision-maker authority over the living will.

Why should you fill out such a form in the first place? The reasoning as an American and as a Jew can be very different. In American bioethics, it is to preserve patient autonomy. This is based on a deep American commitment to individual liberty.

Most of us, however, are not trained in medicine. For instance, when I was helping my mother-in-law fill out her advance directive and we began talking about what interventions she would want, she first said she wanted “everything.” Then when I described to her exactly what was involved in each of the interventions listed in the will, one by one, she said “Oh, I wouldn’t want that!” — and it turned out that she did not want anything except to be kept comfortable through medication. So the very process of filling out an advance directive helps to clarify what a person really wants.

Even so, there are problems with the American rationale for advance directives. First, nobody knows exactly how they are going to die, and advance directives can ask only about some common issues that people face when they are dying. So it is quite possible that the directive will not address the actual questions that a person will face altogether. Furthermore, even if the directive discusses the exact condition that the patient ultimately has, how do we know that what the person said two years ago — before facing the ravages of a disease, perhaps — is what the person wants now?

With advance directives, as with any document, there are often problems of interpretation. If, for example, the patient wrote he does not want any “heroic” measures to keep him or her alive, how do we know what that means? Or what happens if the patient wrote that she does not want to be kept alive if she cannot recognize her near relatives, but she sometimes identifies them correctly and sometimes not?

Finally, the dirty secret is that despite the legal requirement that physicians follow an advance directive, doctors will usually consult family members or surrogate decision-makers and follow their wishes rather than abide by whatever is written in a directive — or at least try to get them to agree to interpret the directive in a particular way and to follow it with that understanding. This is because after the patient dies, the patient will not sue the doctor, but any one of the family members might.

A better reason for filling out an advance directive is for the Jewish concern for family harmony. You want to avoid situations that I have seen all too often, where, let us say, there are three adult children and two of them agree with the doctors that there is no hope that Mom will recover to what she would consider meaningful life and so they want to remove life support so that she can die in peace, but one of them wants to keep Mom on life support forever.

To help families avoid those situations, make multiple copies of the advance directive and give one to your primary care physician, lawyer and each of the adult members of your family. Then call a family meeting. Nobody likes to talk about death, least of all one’s own, but Jews know how to attack a text. You can go over the document, express what you decided and why, and answer questions anyone has. This will enable whoever is designated to make decisions for you to have a sense of what you would have wanted even if you did not specifically address the exact situation that ultimately confronts you as you die. Moreover, whoever makes the decisions for you will not feel guilty in doing so, for he is not imposing his own values but rather acting according to yours. This will not guarantee that the siblings will be able to have good relationships with each other after your death, but it will at least take away one of the sources of possible conflict.

Finally, filling out such a form is important in order to arrange for organ donation. The Conservative Movement’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards has ruled that it is not only an act of chesed (loyalty, kindness) to provide for the donation of one’s organs after death to someone who needs them or to an organ bank; it is a positive obligation to do so. Representatives of all of the movements in Judaism have at least permitted cadaveric organ donation, and most encourage it. Filling out an advance directive enables one to carry out this mitzvah.

Normally, we think that people executing these sorts of documents are fairly advanced in years, for they, we reason, are facing death in the not-too-distant future and therefore need to confront such matters. All of the hard cases in American law, though — cases like those of Karen Ann Quinlan and Nancy Cruzan — have centered on people in their 20s, who statistically are the most likely to be involved in fatal traffic accidents or violence but think of themselves as being invincible. They therefore never communicate to relatives or others how they would want to be treated in the context of critical care.

My own view is that it is important for people to complete an advance directive for health care as soon as they get their driver’s license or as soon as possible. Boomers, keep that in mind for your children and grandchildren — and yourselves if you have not created one yet. The Conservative, Orthodox and Reform movements have all created advance directives in accordance with their own understandings of how to apply the Jewish tradition to our lives. So find the one that fits your outlook on Judaism, fill it out, and have that family meeting soon.

Rabbi Elliot N. Dorff is rector and distinguished professor of philosophy at American Jewish University.

The following websites offer advance directives for different Jewish denominations:

Orthodox: cedars-sinai.edu/About-Us/Spiritual-Care-Department/Documents/RCA_Halachic_Health_Care_Proxy.pdf

Conservative: rabbinicalassembly.org/sites/default/files/public/halakhah/teshuvot/19861990/mackler_care.pdf

Reform: huc.edu/kalsman/articles/URJ,%20Jewish%20Family%20Concerns%20Advance%20Directive.pdf

State of California: http://ag.ca.gov/consumers/pdf/AHCDS1.pdf