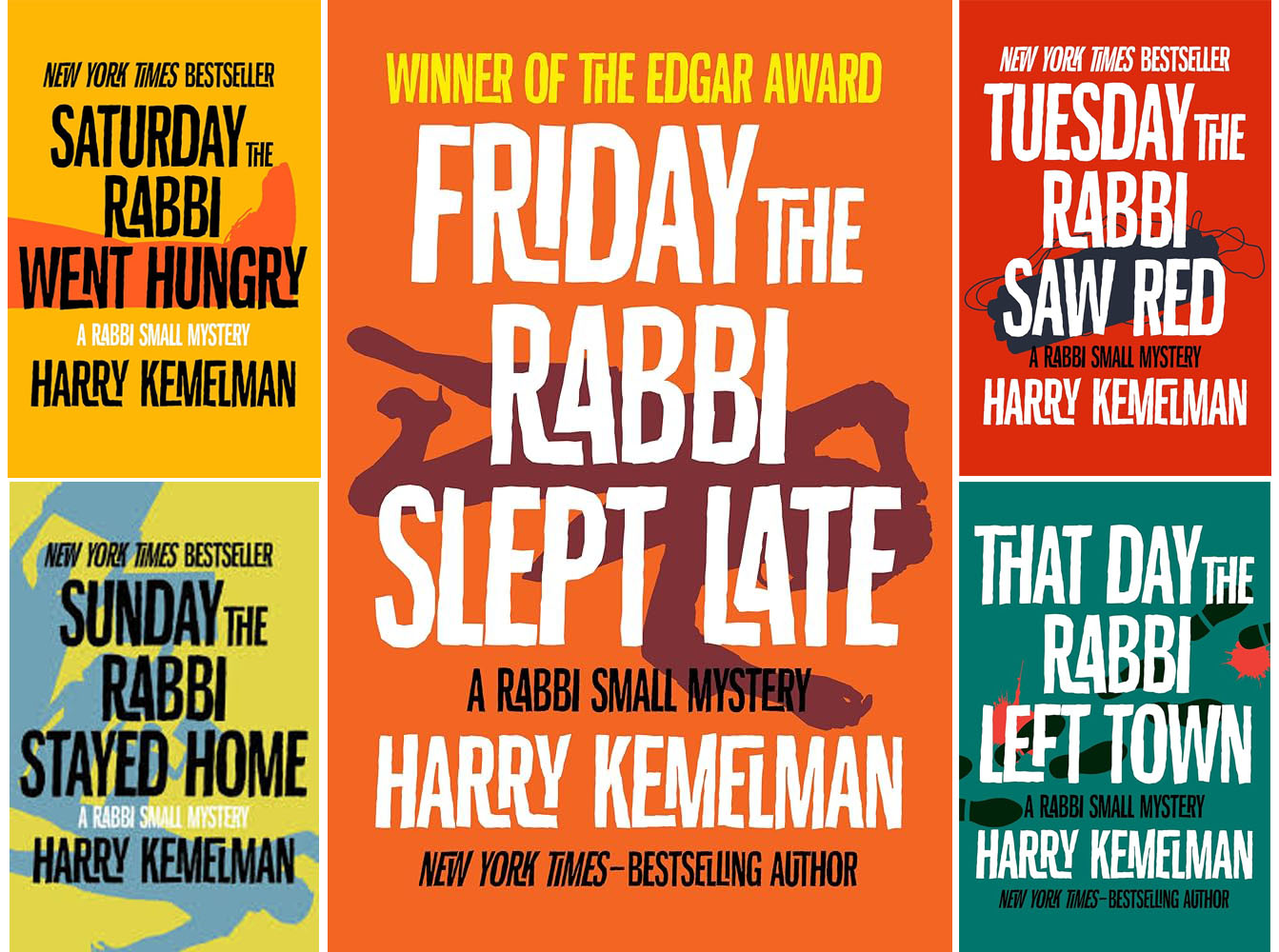

Sixty years ago, a middle-aged English professor named Harry Kemelman wrote a most unlikely bestseller. “Friday the Rabbi Slept Late”—a murder mystery involving the body of a woman found in the parking lot of a synagogue—won an Edgar first best novel prize from the Mystery Writers of America. It went on to spawn a thirty-plus-year series: After “Friday the Rabbi Slept Late” (1964), Kemelman published “Saturday the Rabbi Went Hungry” in 1966 (spoiler: it was Yom Kippur), “Sunday the Rabbi Stayed Home” (1969), and on through the days of the week and beyond until finally, in 1996, “That Day the Rabbi Left Town,” the same year Kemelman left this earth. The books sold millions of copies and were widely loved.

“Friday the Rabbi Slept Late,” as would its successors, follows the conventions of the “cozy mystery” novel. The main character is an amateur sleuth, Rabbi David Small, and it takes place in an enclosed community, Barnard’s Crossing, a fictional Massachusetts town not far from Boston. It includes minimal sex and violence, and a bloodless murder, and is resolved neatly. Yet “Friday” was an unlikely bestseller because rather than use the bulk of its pages to provide clues or suspects for its crime, it instead spends far more time teaching readers about the role of a rabbi, the logic of the Talmud (“pilpul” becomes a favorite term of the police chief, Irish Hugh Lanigan, who loves to roll it across his tongue), and the politics of synagogues (oh, the politics!).

The Rabbi Small series is effective at capturing Jewish life in the American postwar era, that moment of change, that moment of suburbanization and comfort and surprisingly easy assimilation, that moment in which the past—and it’s a particularly nostalgic, Eastern European past, a past that was at the exact same time, in 1964, being mythologized in “Fiddler on the Roof” on Broadway—and the present-day American reality were really coming to a head. Our hero, a newly ordained, Conservative, Ashkenazi (and highly Ashkenormative) rabbi hired by a wealthy community, is a liminal, almost Janus-faced figure. On the one hand, Rabbi Small looks back to a time when the rabbi’s job was to learn Jewish law and sit judgment over his people. And on the other hand, he is young, beardless, and interested in youth culture (even, in the third book, weed). He is a man about to start a family when the series begins, and we see him learning to be lenient about Halacha, for instance, permitting and even encouraging others to accept the use of electricity on Shabbat and holidays.

Rabbi Small describes himself as wanting to be a rabbi like his father and grandfather, a rabbi who would influence his congregants. But in the period of flux that was the 1960s, he worried that he (and other rabbis, along with the classical traditions of Judaism) no longer had a meaningful role: “I’m beginning to think,” he says early on, “that there is no place for me or my kind in a modern American Jewish community. Congregations seem to want the rabbi to act as a kind of executive secretary, organizing clubs, making speeches, integrating the temple with the churches.” Rabbi Small refuses interfaith work, social action, and other “trends” that he doesn’t think are his job.

I picked up the first Rabbi Small book soon after semi-hate-but-also-love-watching “Nobody Wants This,” aka the “hot rabbi show.” Rabbi Noah Roklov, played by Adam Brody, is kind, thoughtful, and remarkably good at listening to and learning from other people; that is not, I thought right away, how rabbis are usually presented in popular culture. Or are they? Fictional rabbis, I realized, vary. They are at times strict and fiery orators, like that of Modernist writer Henry Roth in “Call it Sleep” (1934), or in Philip Roth’s “The Conversion of the Jews” (1958), or in the Bukharan community portrayed in the film “Yismach Chatani” (“The Women’s Balcony,” 2016). They are sometimes providers of comic relief, as in the French bigot-turned-rabbi and Arab-leader-turned-rabbi in the iconic French film “Les Aventures de ‘Rabbi’ Jacob” (1973), or ancient figures, reminding that we must hold fast to our heritage, like Rabbi Isidor Chemelwitz in Tony Kushner’s “Angels in America” (1991) (played brilliantly by Meryl Streep for HBO, 2004). There are, more recently, even variations of the “beautiful” and “fertile” (or infertile) “woman rabbi,” as in Charlotte Mendelson’s female pioneer-graduate of Britain’s Leo Baeck College in “When We Were Bad” (2007) or Rabbi Raquel on “Transparent” (2014-19). Their representations tell us much about the ways not only rabbis but also Jews in general have been seen and see themselves (or want to see themselves) in the world around them. They also give us insight into evolving ideas of gender, class, race, ethnicity and sexuality, national and community norms, and religious leadership in multicultural, often secular, contexts.

I picked up the first Rabbi Small book soon after semi-hate-but-also-love-watching “Nobody Wants This,” aka the “hot rabbi show.”

I had the opportunity to talk about Rabbi Small at a rabbinical college recently. The students were incredible: keen, engaged, enthusiastic. Even the professor-rabbi at the back of the class, who, like the students, had never heard of Harry Kemelman, was rapidly taking notes on the wisdom of Rabbi Small. But then one student raised his hand and asked why, why, when we could learn so much the period in which they were written as well as their timeless insights, were so few people now reading these books?

I looked around the room. The students—this was at a Reform seminary—comprised men both gay and straight, non-binary individuals, and, as a clear majority, women. I thought of Rebbetzin Small, whose main job in the series is to wash dishes, or worry about how dishevelled her luftmensch husband appears, or hover over him as he eats the food she prepares for him. I thought of Rabbi Small denigrating the Women’s Lib Movement as a “shift in fashion.” There are very good reasons they’ve lost their popularity.

But, if I’m honest, I’m still enjoying them. And I’m heartened to see they’ve inspired books that tell us a lot about our time, like Rachel Sharon Lewis’s “The Rabbi Who Prayed with Fire” (2021), featuring a Northeastern city (Providence), a crime (arson), and a rabbi (who is a queer woman), which, as soon as I’m done with Kemelman’s series, I can’t wait to read!

Karen Skinazi, Ph.D. is Associate Professor of Literature and Culture and the director of Liberal Arts at the University of Bristol (UK) and the author of “Women of Valor: Orthodox Jewish Troll Fighters, Crime Writers, and Rock Stars in Contemporary Literature and Culture.”

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.