For Rabbi Stuart Halpern’s commentary on “The Enduring Story of Esther in America,” click here.

The year is 1853, the place is a Women’s Rights Convention in New York City, and the speaker is Sojourner Truth, a woman who has escaped from enslavement in the South. She is illiterate, but she knows her Bible stories.

“Queen Esther come forth, for she was oppressed, and felt there was a great wrong,” she told the crowd, “and she said I will die or I will bring my complaint before the king. Should the king of the United States be greater, or more crueler, or more harder?”

No other biblical text is richer with meaning for American Jews than the Book of Esther, as Rabbi Dr. Stuart W. Halpern points out in his introduction to “Esther in America: The Scroll’s Interpretation in, and impact on, the United States,” a co-publication of Maggid Books, an imprint of Koren Publishers Jerusalem, and the Zahava and Moshael Straus Center for Torah and Western Thought at Yeshivah University. As editor of the book, Halpern assembled two dozen essays from an impressive roster of accomplished scholars, each of whom offers a modern midrash on the meanings of Esther in the American Diaspora.

“Sojourner Truth’s usage of Purim as a prism through which to view her fight for equal rights was no anomaly,” Halpern explains. “Throughout our history, Americans have turned to the Scroll of Esther, the megilla, as they navigated their liberties, morals, passions, and politics. These recurring references are no accident. Rather, they reflect an appreciation of a story whose themes – freedom, power, fraught sexual dynamics, ethnicity, and peoplehood – continue to define American identity to this day.”

“Throughout our history,” Halpern writes, “Americans have turned to the Scroll of Esther, the megilla, as they navigated their liberties, morals, passions, and politics. These recurring references are no accident.”

Thus does Halpern set the table for a banquet of rich and varied scholarship. We learn that Esther attracted the attention of Christian leaders in America as far back as the colonial era, including Anne Bradstreet, the first published poet in America, and Cotton Mather, the prolific author and fiery sermonizer. Early advocates of American independence likened George III to Ahasuerus, thus shifting the blame for British oppression to the royal counselors rather than the king himself. An early abolitionist named Angelina Grimké, addressing a pamphlet to “the Christian women of the South,” asked: “Is there no Esther among you, who will plead for the poor devoted slave?” And Rabbi Tzvi Sinensky, one of the contributors to “Esther in America” who seeks to understand and explain Esther’s “inner experience,” argues that we should “turn to an unexpected source: Hester Prynne, the central character in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s nineteenth-century classic ‘The Scarlet Letter.’”

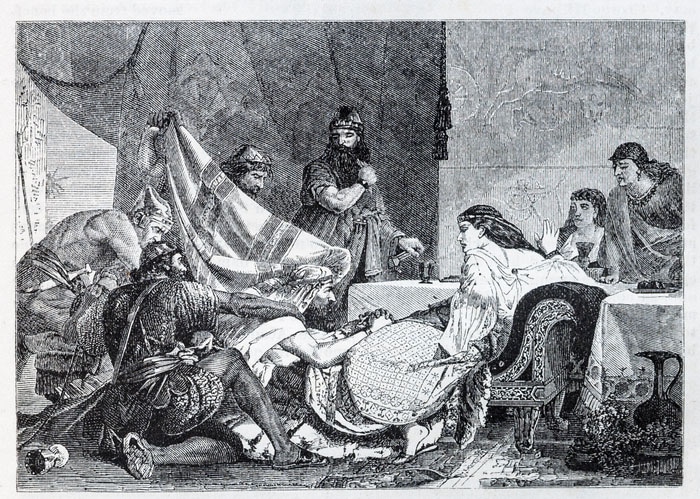

Esther, as the various contributors concede in one way or another, is a problematic role model. She came to be the queen of Persia through a kind of beauty contest. She concealed her Jewish identity and her Jewish name, which is why the title of the scroll in which her story is told identifies her as Esther rather than Hadassah. Above all, she succeeded in saving her fellow Jews by imploring the Persian king to rescue them, a role that casts her as a pleader rather than a leader. Yet the essayists in “Esther in America” agree that Esther deserves to be regarded as heroic.

“Esther went from being an object to having subjects, from a vulnerable orphan in exile to a position of prestige in Ahasuerus’ vast empire, a position that materially elevated her life but one that initially accorded her little power,” argues Dr. Erica Brown in a contribution titled “Finding Her Voice: Black Female Empowerment and the Book of Esther.” Enslaved black women “heard in Esther a female voice of heroism worthy of emulation.” And Brown concludes: “Unlike Esther, these women would not live to see their battles won, but, in speaking out, they added important and critical voices to the American annals of emancipation. Inspired by a woman they never met, these abolitionists paradoxically influenced generations of women they never met, reminding us that ‘history is not of such a black and white character.”

Some of the contributors find moments of ironic humor in the saga of Esther. Dr. Shaina Trapedo, for example, calls our attention to the “Queen Esther contest” that was held in 1933 to crown the “Prettiest US Jewess.” (The prize was a trip to Palestine, but the winner was accused of being secretly married and thus ineligible to wear the crown.) Trapedo insists that the biblical Esther was a “reluctant contestant” in the beauty contest that brought her to the attention of the king, and she observes that “the Talmud suggests that her character was more lovely than her countenance,” which prompts her to quip that “a more fitting title might have been Miss Congeniality.”

Above all, Trapedo argues that Jews in the modern Diaspora found in Queen Esther a source of Jewish pride, and even the beauty contests can be seen as “acts of self-preservation and aspiration” rather than debasement. “Being placed on a pedestal seems like the last thing the biblical heroine would have wanted,” Trapedo writes, and yet, “[u]nlike any other biblical narrative, the Book of Esther offers a model of a people who do not have the luxury of relying on God’s presumed favor and instead shape their own destiny based on merit, ingenuity, and self-reliance consistent with the American dream.”

Above all, Trapedo argues that Jews in the modern Diaspora found in Queen Esther a source of Jewish pride.

Trapedo is alluding to another awkwardness in the Book of Esther, where God is not mentioned. But Halpern himself points out that the only words attributed to Mordecai allow us to conclude that God is present even if not named. By doing so, he joins the other contributors in elevating Esther to the lofty stature that she plainly deserves, not as a figure on a pedestal but as a human role model.

“Do not imagine that you, of all the Jews, will escape with your life by being in the king’s palace,” says Mordecai. “On the contrary, if you keep silent in this crisis, relief and deliverance will come to the Jews from another quarter, while you and your father’s house will perish. And who knows, perhaps you have attained to royal position for just such a crisis.”

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.