Now that we’ve just finished two seders celebrating ourescape from Egypt, a new exhibit at the Skirball Cultural Center demonstratesthat not every Jew got out of Egypt — or wanted to.

“Jewish Life in Ancient Egypt: A Family Archive From theNile Valley,” revolves around 2,500-year-old papyrus scrolls from a cache ofhundreds unearthed on Elephantine Island — the oldest extra-biblical evidenceof Jews in Mitzrayim.

The exhibit is the latest in a trend of document-based artshows, such as 1998’s “Sigmund Freud: Conflict & Culture,” which illuminatehistory through the display of papers and related objects.

“Jewish Life” comes alive through the remarkable,Aramaic-language scrolls, which describe a Jewish community on lush Elephantine800 years after the biblical exodus. Apparently there were no hard feelings,because these people were descendants of Jews who had voluntarily returned to Egyptafter the Babylonians conquered Jerusalem in 586 B.C.E. While elite Jews wereforced into exile in Babylonia, many soldiers and common folk relocated to Egypt,which proved to be a multicultural mecca, not an anti-Semitic hellhole,according to the exhibit.

The core of the show is eight legal documents that belongedto an interfaith family in the fifth century B.C.E, when the religiouslytolerant Persians ruled Egypt. The papyri tell of Ananiah, an official at the Temple of Yahou (a.k.a. Yahweh), and his wife, Tamut, who, in a twist on the haggadahstory, was an Egyptian slave owned by a Jewish master, Meshullam (he allowed herto marry and to own property, per the custom of the day).

According to a real estate deed from 437 B.C.E, Ananiah andTamut bought a two-story mud brick fixer-upper on the main drag in Khnum, avillage named for an Egyptian deity. Their neighbors included Persian soldiersand an Egyptian who managed the garden in the local temple dedicated to Khnum.

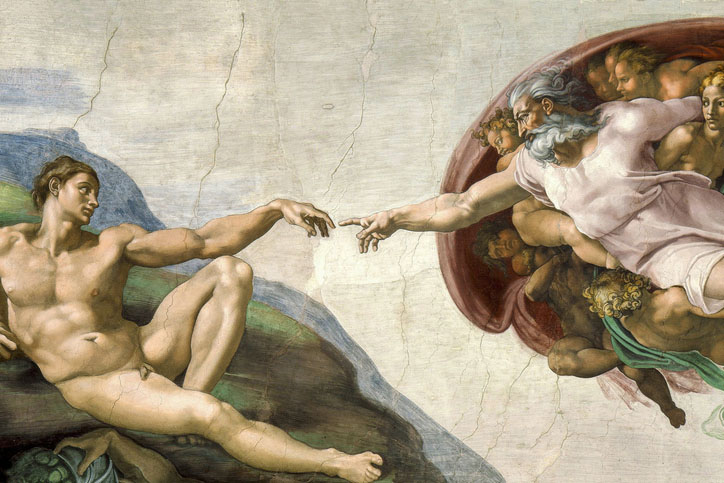

Like his fellow Egyptians, Jewish Ananiah probably continuedthe traditional form of Israelite worship that had been practiced in pre-exilic Judah. He likely burned incense to Yahweh, performed animal sacrifice andworshipped deities such as the queen of the heavens, who in the Elephantinearea had a temple across the river from Yahou’s. This kind of “monotheism-lite”apparently enraged the prophet Jeremiah, who rebuked Egyptian Jews for “makingsacrificial smoke to other gods” in the Hebrew Bible.

According to the Elephantine papyri, local Jews swore oathsto regional deities. Sharing religious and cultural traditions was de rigueur,as evidenced by the exhibit’s papyri and accompanying artifacts. A headless butstill stately statue of Ptahhotep, an Egyptian treasury overseer, wears Persianrobes and an Egyptian chest ornament. A quirky terracotta sarcophagus lid froma Jewish cemetery suggests that some Jews were buried in anthropoid stonecoffins resembling those of their Egyptian neighbors. At the Skirball, theexhibit, which originated at the Brooklyn Museum, will feature five-inchceramic figurines of Astarte, the queen of the heavens, worshipped by Jews andnon-Jews on Elephantine.

“The show is fascinating because it depicts how differentcultures and communities lived in harmony on one small island,” said TalGozani, the Skirball’s associate curator.

“It’s especially relevant because when we think of Jews inEgypt, we think of the Exodus, not of the tranquil Persian period,” said ErinClancey, the museum’s associate curator of archaeology.

Even the exhibition’s origins were multicultural. It beganwhen farming families found Ananiah’s archives on Elephantine in 1893 and soldthem to pioneering American Egyptologist Charles Edwin Wilbour, who stashedthem in a tin biscuit box at the bottom of a trunk. There they languished untilhis daughter found them and donated them to the Brooklyn Museum in 1947.

Cut to 1999, when the museum’s Edward Bleiberg, anEgyptologist and Reform Jew, read the papyri and began turning them into anexhibit.

“I immediately felt a strong connection to these ancientpeople,” he told The Journal.

Bleiberg, like Ananiah, is married to a non-Jew, in hiscase, a Methodist from a small town in Georgia. He had recently purchased a750-square-foot fixer-upper — about the same size as Ananiah’s — in a diverseneighborhood in Brooklyn.

As Passover approached last week, he noted one otherconnection to Ananiah: The Egyptian Jew celebrated the holiday, albeit arudimentary form, as evidenced by a document unearthed at Elephantine thatrefers to a “festival of unleavened bread.”

Written long before the codification of the currenthaggadah, the letter calculates the dates that Elephantine Jews were to abstainfrom bread in 419 B.C.E., based on the Jerusalem lunar calendar.

As for Ananiah’s specific observance, he probably ate matzahmade from millet, an Elephantine crop, and enjoyed some kind of culinary feast,the curator said.

“He may have been aware of the basic story of Passover, buthe had to see it as something he didn’t take literally,” Bleiberg added.”Passover must have been a problematic holiday for Egyptian Jews, because theywere celebrating leaving Egypt, and yet they were still there.”

And, as the exhibit shows, no boils, frogs or locusts provednecessary.

The exhibition opens April 30 and runs through July 18.On May 2, Edward Bleiberg will discuss “Scenes From a Marriage: A Jewish FamilyArchive From Ancient Egypt.” For more information about the exhibition, call(310) 440-4500 or visit www.skirball.org . p>