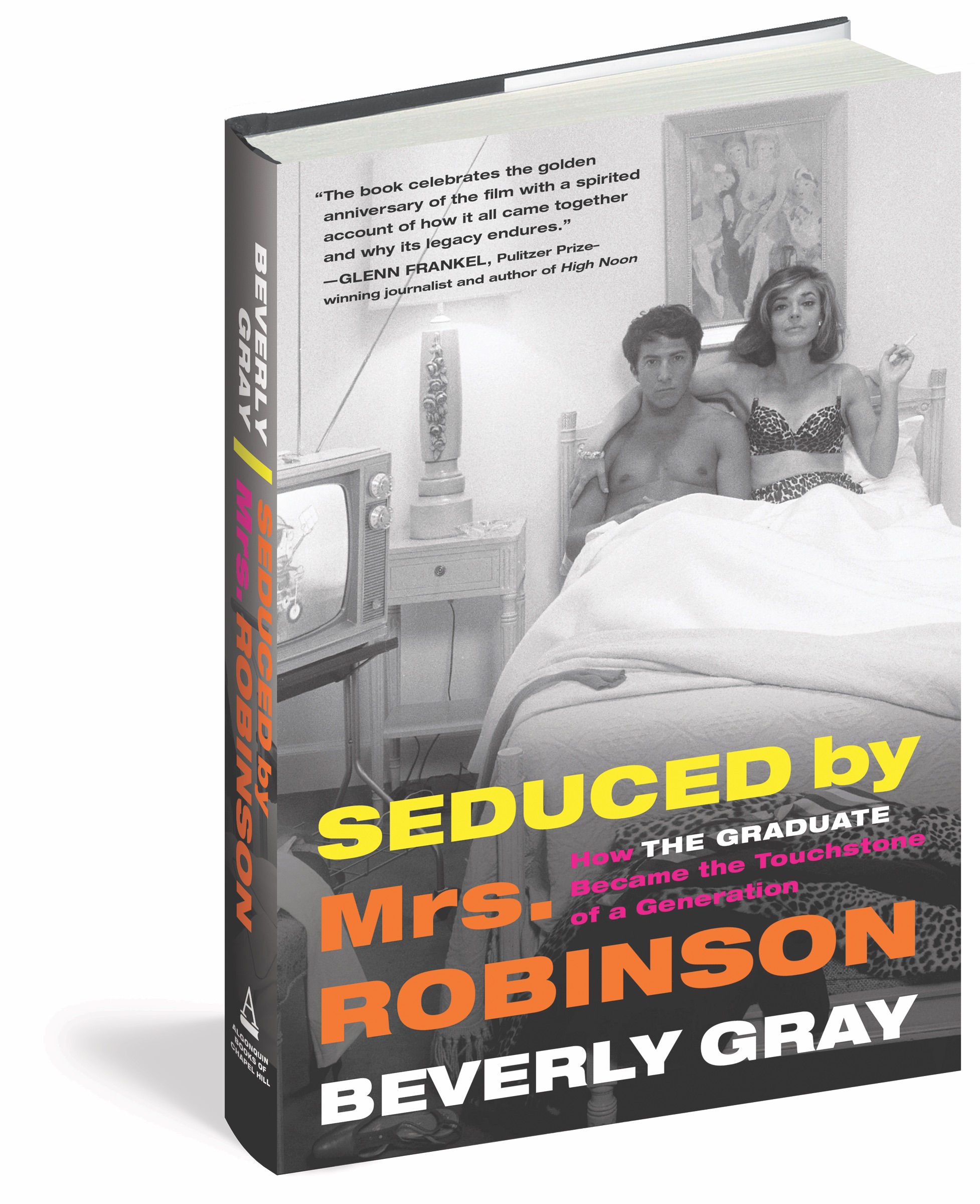

When it premiered in 1967, no one predicted “The Graduate” would amount to much. It was, as Beverly Gray writes in “Seduced by Mrs. Robinson: How ‘The Graduate’ Became the Touchstone of a Generation” (Algonquin), “a small, sexy comedy based on an obscure novel by a first-time author.” But the movie captured the hearts and minds of the baby-boom generation, then in its teens and 20s, and it remains an important cultural artifact a half-century later.

“Today ‘The Graduate’ continues to serve as a touchstone of that pivotal moment just before some of us began morphing into angry war protesters and spaced-out hippies,” Gray explains. “Many who today carry AARP cards once saw ‘The Graduate’ as a sexy romp or as a rallying cry for the concept of self-determination.”

Gray brings some impressive credentials to her work. Rare among entertainment journalists and Hollywood biographers, she earned a doctorate in American literature from UCLA and spent a decade as story editor for the celebrated movie producer Roger Corman. She has written about the entertainment industry for the Hollywood Reporter and the Jewish Journal, among other publications, and she is the author of biographies of Corman and Ron Howard.

Above all, she was one of those unsettled baby boomers for whom “The Graduate” was nothing less than a revelation. “Hey, wasn’t that me up there on the screen?” she writes of her own reaction to the movie when she saw it for the first time.

What I admire most about “Seduced by Mrs. Robinson” is Gray’s penetrating investigation of how the movie was actually made, a behind-the-scenes saga that begins with Charles Webb’s 1963 novel.

The tale she tells fairly sparks with synchronicities. The publisher of the novel was David Brown, who would score his own Hollywood success as the producer of “Jaws.” The cover of the book was designed by Milton Glaser, a graphic artist who influenced the look and feel of pop culture throughout the ’60s. The young producer who optioned the book — for only $1,000 because no one else was bidding — was Lawrence Turman, whose sparse credits included a movie based on Gore Vidal’s “The Best Man,” and who now heads the Peter Stark Producing Program at USC.

By the end of the fascinating backstory that Gray tells, we understand exactly why the movie is called a classic.

A novice director named Mike Nichols, best known as a stand-up comedian (with Elaine May), had scored a hit on Broadway with playwright Neil Simon’s “Barefoot in the Park” and saw “The Graduate” as his opportunity to break into movies. When Nichols found himself commiserating with a fellow displaced New Yorker named Buck Henry at a Malibu beach party hosted by Jane Fonda, Nichols realized that he had found the screenwriter he needed. And studio mogul Joseph E. Levine, who broke into the movie business with “a cheap Italian sword-and-sandal epic called ‘Hercules,’ ” agreed to finance the movie.

The unlikeliest break came when Turman and Nichols were casting the lead role of Ben Braddock, a part they predicted would “make a star of the actor who is chosen.” Robert Redford, John Glover, Edward Herrmann, Harvey Keitel, Tony Bill and Charles Grodin all were considered — and rejected. The producer and director agreed that “Benjamin needed to be tall, blond and California handsome,” and the actor who played the role needed to be plausible as a 21-year-old. And yet Nichols offered the job to a 30-year-old Jewish actor who had grown up “hypersensitive about his ethnicity, his short stature, [and] his prominent nose,” Gray observes.

“This part is not for me,” Dustin Hoffman told the director. “An ethnic actor is supposed to be in ethnic New York in an ethnic Off-Broadway show. I know my place.”

Gray points out that Nichols — born Michael Igor Peschkowsky — “was, beneath his self-confident exterior, both the ultimate Jewish outsider and a funny-looking guy.”

The chemistry between these odd bedfellows is now a matter of history, of course, but Gray continues to enrich our understanding of how the movie came into existence. The soundtrack, for example, features several memorable Simon and Garfunkel songs, but Gray reveals that the song most closely associated with the movie — you know the lyrics: “And here’s to you, Mrs. Robinson” — was not fully written and recorded until the year following the movie’s release, when it appeared on the “Bookends” album. What we hear on the film’s soundtrack was “a little ditty with which [Paul] Simon had been toying,” and the “scrap of a tune” is used in the movie as “traveling music to accompany Ben’s drive up the California coast.”

Gray reminds us that the critics were not unanimous in their praise when the movie was released. “It’s a shame — they were halfway to something wonderful when they skidded on a patch of greasy kid stuff,” complained Richard Schickel in Life magazine.

But at least a few critics understood the deeper and enduring qualities of what they were seeing on the big screen. Charles Champlin, the film critic of the Los Angeles Times, wrote in 1971: “No small part of the phenomenal success of ‘The Graduate’ was that it gave expression — funny expression — to a youthful restlessness and dissatisfaction that was in the air like marsh gas, waiting to explode.”

By the end of the fascinating backstory that Gray tells, we understand exactly why the movie is called a classic.

“ ‘The Graduate’ lasts partly because it offers something for everyone: the restless youth; the disappointed elder; the cinephile who values the artistic innovation that’s the legacy of director Mike Nichols,” Gray writes. “And this film has also burrowed its way into Hollywood’s dream factory. The American movie industry, which worships box-office success, has learned from ‘The Graduate’ brave new ideas about casting, about cinematic style, about the benefits of a familiar pop music score.”

Perhaps the greatest compliment I can bestow on this accomplished and compelling book is to say that Gray will send you rushing to Netflix to watch “The Graduate” again, and when you do, you will see a familiar movie in an entirely new way.

Jonathan Kirsch, author and publishing attorney, is the book editor of the Jewish Journal.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.