Donald Trump was in Phoenix for a speech on immigration, and Shmuly Yanklowitz wasn’t happy about it.

On a late August day, as temperatures topped 100 degrees, the outspoken Orthodox rabbi strode into a busy intersection carrying a sign written with colorful markers that said, “Hate is not welcome in our town.” But first, he threw his prayer shawl over his shoulders.

“I almost always wear my tallis for street protests,” Yanklowitz said in a phone interview from his Phoenix office last week. “And that’s because those protests are a form of prayer for me. I view it as a conversation in partnership with God to be at street protests, to stand in solidarity with vulnerable populations.”

Yanklowitz’s burgeoning rabbinical career (he’s only 35) has focused on bridging the gap between what he calls the “parochial and the universalistic” — between a Judaism centered on rote ritual and one emphasizing social justice, even at the expense of spiritual practice.

His latest book, a collection of essays called “Torah of the Street, Torah of the Heart,” lays out the tenets of his faith. It offers a wide-ranging look at the rabbi’s theology and the social action it inspires.

In addition to examining the pillars of his belief, the book covers a number of issues that are, on their face, secular ones. He advocates for an end to the death penalty, outlines the spirituality of a plant-based diet (Yanklowitz is a practicing vegan) and details some of his personal journeys in social justice.

In the summer of 2015, for instance, he donated one of his kidneys to a complete stranger, an experience that made him a believer in a regulated organ market.

“I had simply realized that I couldn’t bear to have two healthy kidneys while knowing someone out there would certainly die of renal failure,” he writes.

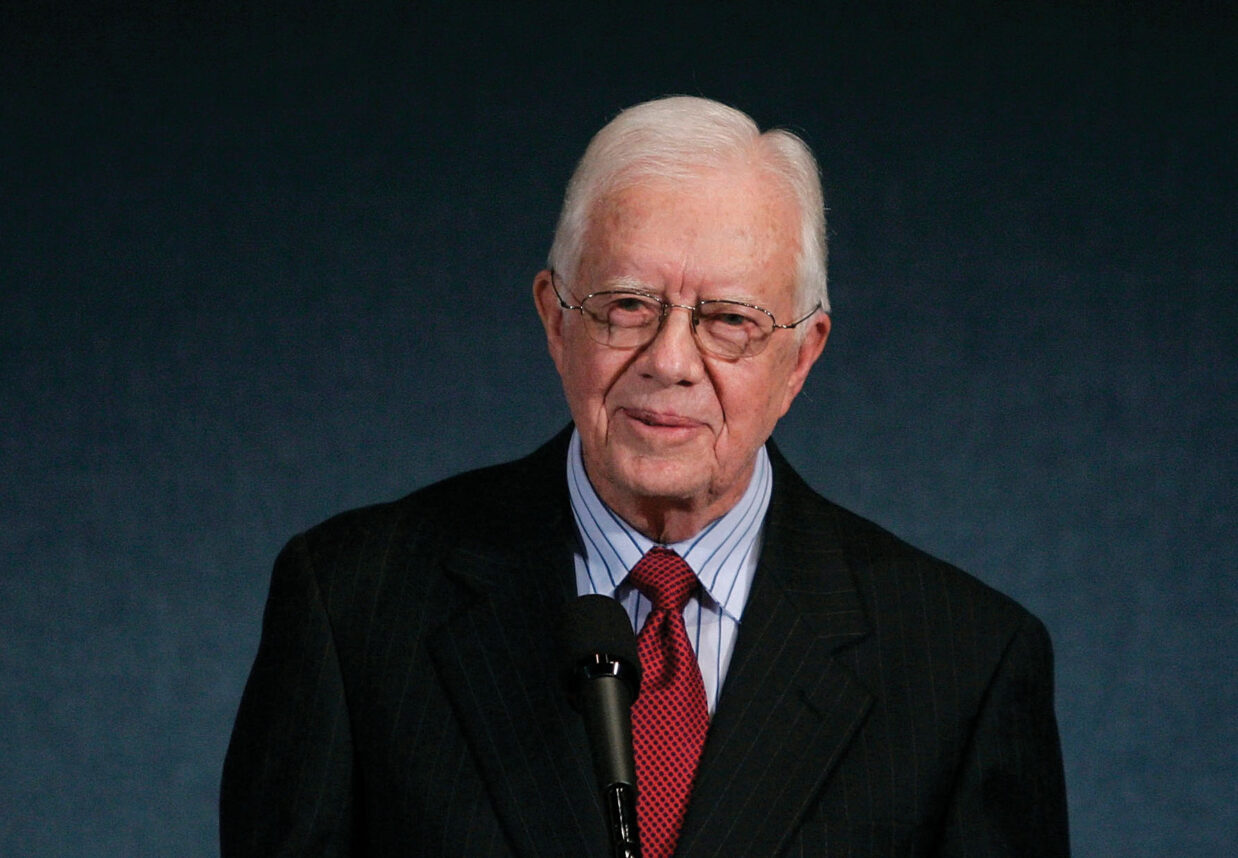

In person, Yanklowitz speaks with the deliberateness of a religious leader and the magnetism of a politician.

Towering and muscular, Yanklowitz talks at an enthusiastic clip. When he flashes his characteristically wide and toothy smile, dimples appear over a strong chin. He speaks the same way he writes: with kavanah, intention. Interactions with Shmuly Yanklowitz don’t fade quickly from memory.

At one time, Yanklowitz must have seemed an unlikely candidate for the work of reanimating American Judaism.

Born to a Christian mother and Jewish father, he became fascinated as a teen with the precepts of his father’s Jewish faith. Over the course of adopting Judaism, he underwent two conversions, a liberal one and an Orthodox one, experiences he has subsequently drawn on to write about controversies in Jewish conversion.

After college, he took a job in corporate consulting for about six months, until he realized it was soul-crushing work. He quit and a week later moved to Israel to work toward ordination.

While living and working as an observant Orthodox rabbi, his secular upbringing seems to be reflected in a willingness to veer from the traditional rabbinical script. Notably for a book that’s ostensibly about Judaism, many of the essays in “Torah of the Street, Torah of the Heart” don’t cite a single text or Jewish ideal.

“I have deep Chasidic leanings in that I think that I feel very comfortable with the secular, because I think that the secular is made holy through our engagement to elevate it,” he told the Journal.

Yanklowitz is not only tolerant of the secular but sees challenges to the faith as integral to strengthening it. In one essay, he quotes Rabbi Nathan Lopes Cardozo, one of his own teachers in Israel: “I love heresy because it forces us to rethink our religious beliefs. We owe nearly all of our knowledge not to those who have agreed but to those who have differed.”

But he sees the status quo in Judaism as fraught with increasing disengagement between secular Jews and Orthodox ones, a dangerous trend that can be reversed only by a commitment on both sides to religious humility.

“If Jewish people today from any walk of the faith are still committed to a notion of klal Yisra’el [the community of Israel], are committed to a notion that we are still one people, then we have to all make concessions — then we have to adjust our thinking in some way that accounts for people who think differently from us,” he said.

To that end, much of his work has been directed toward waking up secular Jews to their Judaism, on the one hand, and, on the other, marshaling awareness among the Orthodox for social justice causes.

In addition to his role as the president and dean of Valley Beit Midrash in Phoenix, he runs two Orthodox advocacy groups: Uri L’Tzedek, which focuses on social justice issues writ large, and the Shamayim V’Aretz Institute, an animal welfare group.

Throughout those engagements runs a commitment not to Jewish social justice work but “Jewishly rooted social justice work,” activism that he says borrows from and is motivated by “unique Jewish wisdom and nuance.”

For Yanklowitz, a prerequisite to doing good work is having one’s spiritual house in order. The idea is that before looking outward, one must look inward for inspiration.

“The greatest threat that we experience today is an apathy where our fire is burnt out or, even more tragically, it was never lit at all,” he said.

He continued, “The one spiritual imperative is to ensure that we’re living a passion-filled life. And to do that means we can’t follow some cookie-cutter model of Judaism. It means we all have to find our own model that really works to keep that passion alive and that overflows from us.”

Too many Jews, in his view, fail to find that model. He outlined the two poles of modern Jewry as fundamentalists who are “consumed by their own fire” and secularists who “don’t have a fire at all.”

Instead, he held up the burning bush of the Exodus story as a symbol of a healthy spirituality: kindling that burns but is not consumed.

“We’re to be on fire in a way that’s healthy and produces light, not heat,” he said.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.