In “Night,” Eli Weisel recounts seeing a Jewish child die by hanging during the Holocaust.

“Where is God?” someone called out.

“This is where,” Weisel said in his heart. “Hanging here from this gallows …”

The question, “Where is God?” is the central question posed to us by the Holocaust, by the sheer magnitude of the destruction, the debasement of all human value, and the mass-production of suffering.

Weisel’s answer, that God was dead — a victim of Nazi cruelty — could have been the final word on the matter were it not for two other historic developments that took place in the 20th century.

In Israel — the creation of a sovereign Jewish state and the return of the Jewish people to their ancient homeland for the first time in two millennia.

In the United States — a golden age of Jewish prosperity and social mobility.

These developments retroactively changed our perception of the Holocaust itself. It was no longer just the worst atrocity of its kind in history, but the last of its kind as well. Its final message was one of survival, not destruction.

God received a stay of execution.

In the wake of Oct. 7, however, this post-war narrative of Jewish history has taken a hit. Hamas’ massacre was nothing like the Holocaust in scale, but it nonetheless discredited the notion that the Jewish people, having survived an attempted extermination, would now live happily ever after.

And across the world from Israel, the shocking surge of antisemitism in America that followed Oct. 7 revealed that the Golden Age for Jews was but a brief, anomalous chapter — one which has seemingly come to a close.

And so the question comes rushing back: Where is God?

Rabbi Irving (Yitz) Greenberg has an answer. God is still here. But He’s giving us some space.

Rabbi Greenberg, now in his early 90s, is a renowned scholar, teacher, author and spiritual leader. He is famous throughout the Jewish world for his radical suggestion that the covenant between God and the Jewish people was broken by the Holocaust, an idea that he softens and develops in his new book, “The Triumph of Life: A Narrative Theology of Judaism” (Jewish Publication Society, 2024).

Rabbi Greenberg, now in his early 90s, is a renowned scholar, teacher, author and spiritual leader. He is famous throughout the Jewish world for his radical suggestion that the covenant between God and the Jewish people was broken by the Holocaust, an idea that he softens and develops in his new book, “The Triumph of Life: A Narrative Theology of Judaism” (Jewish Publication Society, 2024).

In this work, Greenberg backs off from the idea that the covenant is broken. Rather, it has entered a new phase, a phase in which God has contracted Himself, so to speak, in order to give humans more freedom.

Like a parent taking their hand off the back of the bicycle, God is letting us ride on our own, which means, of course, that we might fall. “The sobering lesson is that, once human beings took full charge of realizing the covenant, there were no guarantees (or divine controls) to assure the ideal outcome.”

God is not hiding His face to punish us, but rather to push us. God wants us to grow up and reach our full potential as “managing partners” in the work of this world.

For Rabbi Greenberg, this means that it is our job to make sure that human life is valued on earth. When confronted with the forces of death, we mustn’t despair or fall into nihilism. Rather, we must go all in on life.

“Upholding life,” Greenberg writes, “is the core of Jewish teaching, in the Bible and in Judaism’s subsequent orientation to both daily and ritual behaviors.”

This means valuing every single human life as an image of the divine. It also means using our amazing intellectual capacities “to overcome poverty, hunger, oppression, war, even sickness, and thus roll back the realm of death.”

Now, it’s no innovation to say that Judaism values life, but Rabbi Greenberg takes this idea to new depths, suggesting that Judaism calls us to fight death to the very end. “Let us go step by step along the vector of increasing life, curing illness, preventing death, as far as we can go.”

It’s no innovation to say that Judaism values life, but Rabbi Greenberg takes this idea to new depths, suggesting that Judaism calls us to fight death to the very end.

Rabbi Greenberg’s abhorrence of death (“Death is the ultimate contradiction to human dignities”) reminded me of tech billionaire Bryan Johnson, known for his zealous quest to defeat aging and live forever, a quest that has included receiving regular plasma transfers from his own son.

I bring up Johnson to point out that the desire to conquer death can lead somewhere obsessive, dark and post-human. Death, after all, is a part of life. And no religion that embraces life — in all of its fullness — can reject such a crucial part of the human experience as our encounter with our own finitude.

Taken as a whole, the book seeks to reconcile the diverse threads of Rabbi Greenberg’s worldview. As a work of “narrative theology,” it weaves these threads into a cohesive story about God’s relationship with humanity.

It addresses the black hole of the Holocaust alongside the redemptive arc of the state of Israel. It upholds Orthodoxy while embracing social justice causes, including LGBTQ inclusion in Judaism. It reaffirms the covenant but does so on the premise that God will not save humanity from itself.

In this, it aligns with thinkers like Rav Shagar, who reimagine Judaism in ways compatible with postmodern sensibilities.

Yet, in a postmodern era defined by the collapse of grand narratives, Rabbi Greenberg’s very effort to impose narrative coherence on theology seems to undermine his project.

There is something appealing about the idea that God wants us to mature and take greater responsibility for our moral and religious lives. Moreover, the idea has deep Jewish roots. In the famous Talmudic story of the Oven of Akhnai, for instance, God delights when his children defeat him in a Halachic debate.

There is something appealing about the idea that God wants us to mature and take greater responsibility for our moral and religious lives. Moreover, the idea has deep Jewish roots.

But the idea of an evolving covenant, in which God’s role continuously shrinks, at times struck me as a Jewish version of the “God of the Gaps” idea, in which God is invoked to explain phenomena that science has not yet understood — His role shrinking as knowledge expands.

And ultimately, I felt that this theory was too tidy to answer the aching question posed by the unnamed man in “Night.”

That said, I am glad that Rabbi Greenberg no longer sees the covenant as broken. This verdict comes from his observations of Jewish life after the Holocaust. To his amazement, the Jewish people did not walk away from the Torah. Instead, they drew closer.

We still pray, study, keep kosher, wrap tefillin, and welcome Shabbat. We stand under the huppah and bring new children into the covenant. We wash our dead and lay them in the ground. And then we do it all over again.

Rabbi Greenberg’s book is an attempt to justify this, but perhaps it needs no justification.

Betrayed by history and unsure of where God is, what else do we have but this stubborn insistence on life?

Matthew Schultz is a Jewish Journal columnist and rabbinical student at Hebrew College. He is the author of the essay collection “What Came Before” (Tupelo, 2020) and lives in Boston and Jerusalem.

Excerpt from ‘The Triumph of Life’

Responses after the Holocaust

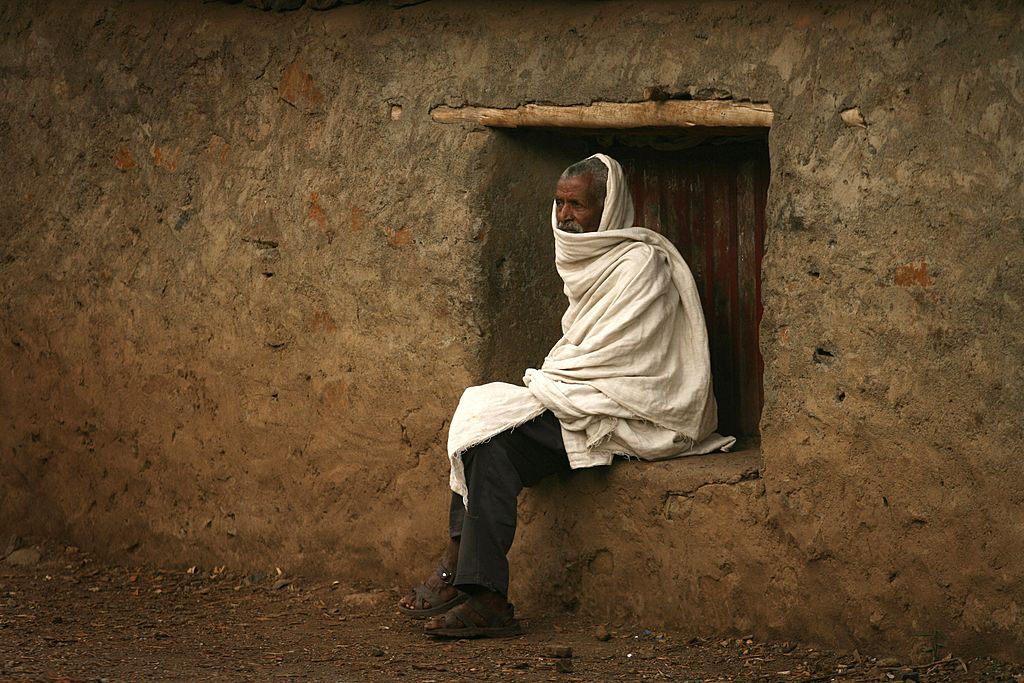

When I first began to respond to the Holocaust theologically, I was under the spell of the traditional view of Divine control of history. I had lived in a universe where God ruled, where every year people were put on trial for their lives, their fate depending on whether they had done more good or more evil in the previous twelve months. Along with Jews worldwide I prayed: “Our Father, Our King, we have no King but You … nullify the plans of those who hate us.”

These views were pulverized in the Shoah. When I read that in the burning pits of Treblinka, if the “[guard] was kind, he would smash the child’s head against the wall before throwing him into the burning ditch; if not, he would toss him straight in alive,” I could not reconcile that with God’s Presence in the world. I am an observant Jew, and all my life I have loved doing the mitzvot. But I went through days when I put on my tefillin and such scenes flooded back into my mind. I choked on the words of the prayers and could not say them. I certainly could not accept that this cruel fate was inflicted on the Jewish people because of their sins.

Why did I not let go of my faith entirely? A lifetime of religious observance and experience held me. Also, my most intense years of immersion in the Holocaust were spent in the Land of Israel (1961–62; 1974–75). Every day there I experienced not only the triumph of death in the Shoah, but the power of life. Walking the streets of Jerusalem, my eyes feasted on neighborhoods restored after thousands of years, and my ears heard the prophet’s predicted “sounds of revelry and joy of groom and bride” (Jer. 33:10–11). In the renewed city, God’s Presence was manifest. I sensed that I was witnessing the renewal of the covenant by the Jewish people and by God. This new birth was reversing the Nazi death blow, and proving that God “had planted eternal life in our very being.” In my mind, the twin death star of the Holocaust and life star of Israel were locked in unrelenting combat. I was totally held by both, and mired in a standoff between their two gravitational pulls.

It became increasingly clear to me that this was not only a personal crisis of my own faith. The existing religious and secular understandings of faith and truth would have to be transformed to be credible in light of the Shoah. Religion as it had existed before the Holocaust had been unable to prevent the Nazis; nor could theology explain their regime of death. Heinrich Himmler, the chief architect of this realm of death, insisted to his confidant, Felix Kersten, that SS men must believe in God, otherwise “we would be no better than the Marxists.” At the same time, sometimes atheists were more able than religious people to understand and respond to the Holocaust. The philosopher Albert Camus, an atheist, described himself yearning and praying in vain for a word from the pope opposing the Final Solution. He expressed his disappointment and disillusion on realizing that being Christian did not make people more likely to support the Resistance. If the Nazis could see themselves as people of faith and see God as integral to their project, if an atheist could understand the absolute need to oppose the horrors of the Final Solution while the pope himself could ignore it, then something must have been wrong with inherited approaches to religion.

In the same way, in the early State of Israel, religion did not seem to predict people’s commitments to protecting the Jewish people. To me, the State of Israel was the most powerful and persuasive proof of the presence of God in history and of the ongoing viability of the covenant. Yet the majority of Jews then populating the Jewish state were nonobservant and secular — and many of them literally gave their lives defending it. In my view, by spending their lives building the homeland, these secular Jews were giving witness and “proving” God’s promises were true, regardless of the fact that many of them would have denied they were doing so and would have even rejected belief in God. By contrast, many ultra-Orthodox Jews in the Land of Israel had exempted themselves from the army to study Torah and engage in religious ritual activities. I concluded that in this world, actions speak louder than words. Religious is as religious does. In Israel, as in the Holocaust, Jews’ degree of religious conviction did not predict their degree of participation in the causes that advance the goal of life and flourishing for the Jewish people.

I struggled to find a conception of religion that would explain how people’s relationships with God could so completely fail to explain their behavior in their greatest moral and political test. I was already moving toward understanding the Shoah as reflecting a new age of greater Divine hiddenness and greater human responsibility, yet I remained mired in the traditional framework of covenant, in which Israel witnessed to God and worked for tikkun, while God directed history and protected Israel. Ultimately, I had to acknowledge the truth in Elie Wiesel’s words: “For the first time in history this very covenant [of reciprocity] is broken.” Protestant theologian Roy Eckardt’s argument also helped sharpen the nature of the crisis. Eckardt claimed that God must repent — we would say, in Jewish terms, must do teshuvah — for having given His chosen people an unbearably cruel and dangerous task without having provided for their protection. Part of me found this compelling. Since God had failed to uphold the covenant by failing to save the people of Israel, therefore, as a just deity, God had to withdraw the covenantal obligation.

It seemed clear to me that, had the covenant between God and the Jewish people been the same as the traditional version, then God’s behavior during the Holocaust would certainly have broken that relationship. But even as I developed these thoughts, the evidence around me showed that the Jewish people continued to live in covenant with God. Although the Nazis had killed an estimated 80% of the rabbis, scholars, and full-time students of Talmud alive in 1939, within a half century, there were more rabbis, scholars, and full-time students of Talmud than ever before, in any age of Jewish history.

I was inspired by the example of Naphtali Lau-Lavie, scion of a devout Orthodox family in Kraków, grandson of a distinguished rabbi who survived harsh labor camps in Hortensia and Czestochowa. He was liberated in Buchenwald at the age of 19, while nearly all of his family had been killed. After his liberation, he spent two weeks without putting on tefillin or engaging in prayers. Then he received a note saying: “You have to say Kaddish because your mother is no longer alive. She died in Ravensbrück.” In that moment, he decided that he would live his life and raise his children in the traditions of Israel, and eventually he came to live in Israel as a fully observant Jew. Although its very basis seemed smashed, the covenant was operating at full blast in Jewish life worldwide.

Trying to reconcile these two contradictory understandings, in a 1982 essay I offered the possibility of a voluntary covenant: “The covenant … was broken but the Jewish people, released from its obligations, chose voluntarily to take it on again. We are living in the age of the renewal of the covenant. God was no longer in a position to command but the Jewish people was so in love with the dream of redemption that it volunteered to carry on its mission.” According to this understanding, God did break the covenant by allowing the Holocaust to happen — but, in practice, the covenant was still functioning, because the Jewish people had chosen to uphold its side of the terms. The covenant had none of its old obligations and enforcement mechanisms, but it remained a commitment and set of actions the Jewish people could take on to further the dream of redemption through partnership with God.