A few weeks following her college graduation, Amy Sohn sat down to eat at a hip vegetarian restaurant in New York. A bespectacled server approached her table.

“I really like your eyeglass frames,” said Sohn.

“Well, Emma Goldman is one of my heroes,” replied the server.

It was the second thing that Sohn had ever learned about Goldman—she wore oval-shaped eyewear. The first tidbit had been that Goldman was an anarchist political icon of the twentieth century.

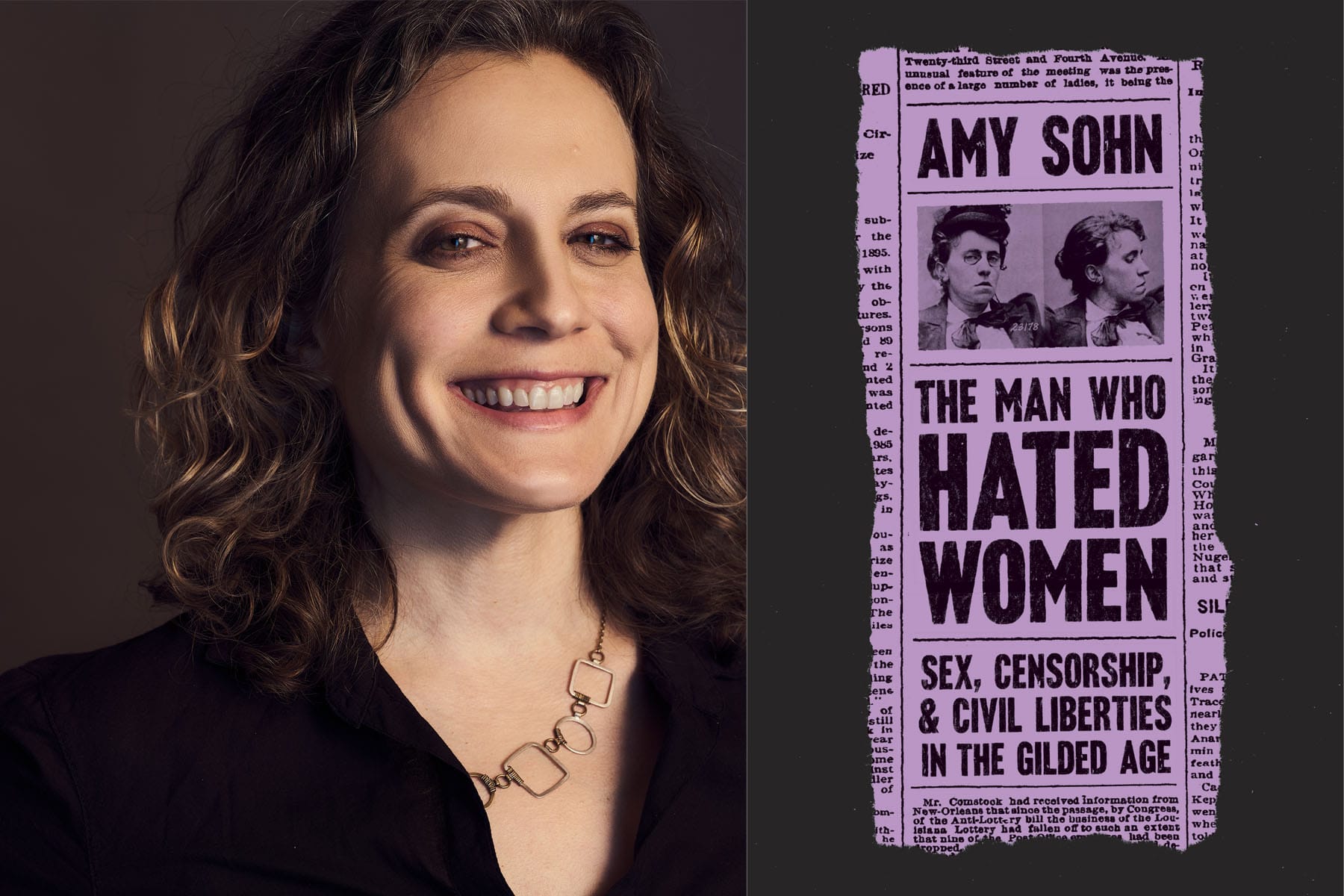

Decades later, Sohn decided to delve deeper while writing “The Man Who Hated Women: Sex, Censorship, and Civil Liberties in the Gilded Age” (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021). “The Man Who Hated Women” highlights the transformative period of Goldman and other “sex radicals,” a group of feminists who supported sexual freedom and opposed marital rape. Unlike celebrated suffragists, such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, many sex radicals became pariahs for speaking up about sex. They tirelessly fought against the Comstock laws, which prohibited any publications related to contraception. Anthony Comstock, “the man who did more to curtail women’s rights than anyone else in American history,” proudly served as secretary of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice. He relished punishing the intellectual radicals, a group that was comprised almost entirely of writers.

“The Man Who Hated Women” highlights the transformative period of Goldman and other “sex radicals,” a group of feminists who supported sexual freedom and opposed marital rape.

“Writers are always drawn to writers’ stories,” Sohn explained over the phone. Like Sohn, Goldman was born to a Jewish family with a knack for journalism. Since women were denied the right to vote or run for office, Goldman created an incendiary political magazine and lectured thousands in German, Yiddish, and English. “I think the thing that people don’t necessarily understand about [Goldman] is that she was such a popular speaker … and so, to me, to realize that one of the most powerful speakers of their generation was a woman and an immigrant and a Jew was truly inspiring.”

Goldman’s experiences working in sweatshops sparked a lifelong passion for the civil liberties movement and women’s rights. She was one of the few “birth controllers” who understood the connection between free love and nineteenth-century radical movements. Although her efforts repeatedly landed her in prison, they ultimately led to the formation of the modern birth control movement.

Sohn vividly details the pivotal roles of several other overlooked activists in “The Man Who Hated Women”—an impressive feat considering barriers to research. Throughout her sleuthing, Sohn found a relatively limited amount of personal details, such as diaries and letters, belonging to women. “I think I’m most proud of the women in the book who nobody’s heard of, which are Ida Craddock, Sarah Chase, and Angela Haywood,” Sohn added, “because I was able to uncover things and write about things that no one else had. It’s very exciting in nonfiction work when you feel like you’re filling in details for the first time.”

Praised by Goldman as “one of the bravest champions of women’s emancipation,” Ida Craddock is depicted as the bridge between the nineteenth- and twentieth-century free speech advocates. “The Man Who Hated Women” argues that the anti-Comstock crusade laid the groundwork for the free speech movement. Craddock, along with other provocative female writers of the nineteenth century, made organizations like the Free Speech League and the ACLU possible.

“I like feminists who credit earlier feminists and do their homework because there’s this tendency to believe that sex was invented in 1969,” Sohn added. “The Man Who Hated Women” sheds light on the different shapes and forms of feminism. Whether they held conservative or sex-positive views, each advocate contributed significant ideas about sex, childbirth and womanhood. Sohn hopes that today’s feminists can find their commonality and bridge the divide among themselves. “What I really respected about these women that I write about is that there was incredible room for variety of opinion and intelligent discourse, disagreement, and discussion in the form of essays, letters, [and] columns in these newspapers.”

Not only does “The Man Who Hated Women” add to the discussion; it demands it. The book compels women to “write, write more, and shout,” as well as openly communicate questions about human sexuality. “Only when we can answer these questions with candor,” writes Sohn, “can we have a feminist movement for this century and beyond.”

Eve Rotman is a writer on the West Coast. Follow her on Twitter @EveRotman

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.

More news and opinions than at a Shabbat dinner, right in your inbox.